Global giants to pay multimillions of tax

Google and Facebook could be forced to pay hundreds of millions in extra tax in Australia under a historic G7 deal.

Global companies such as tech titans Google and Facebook could be forced to pay hundreds of millions in extra tax in Australia under a historic tax agreement by the world’s leading economies that has received bipartisan support in Canberra.

The weekend agreement by the Group of Seven rich nations satisfied a US demand for a minimum corporate tax rate of at least 15 per cent on foreign earnings and paved the way for levies on the world’s largest multinational enterprises in countries where they make money, instead of where they are headquartered.

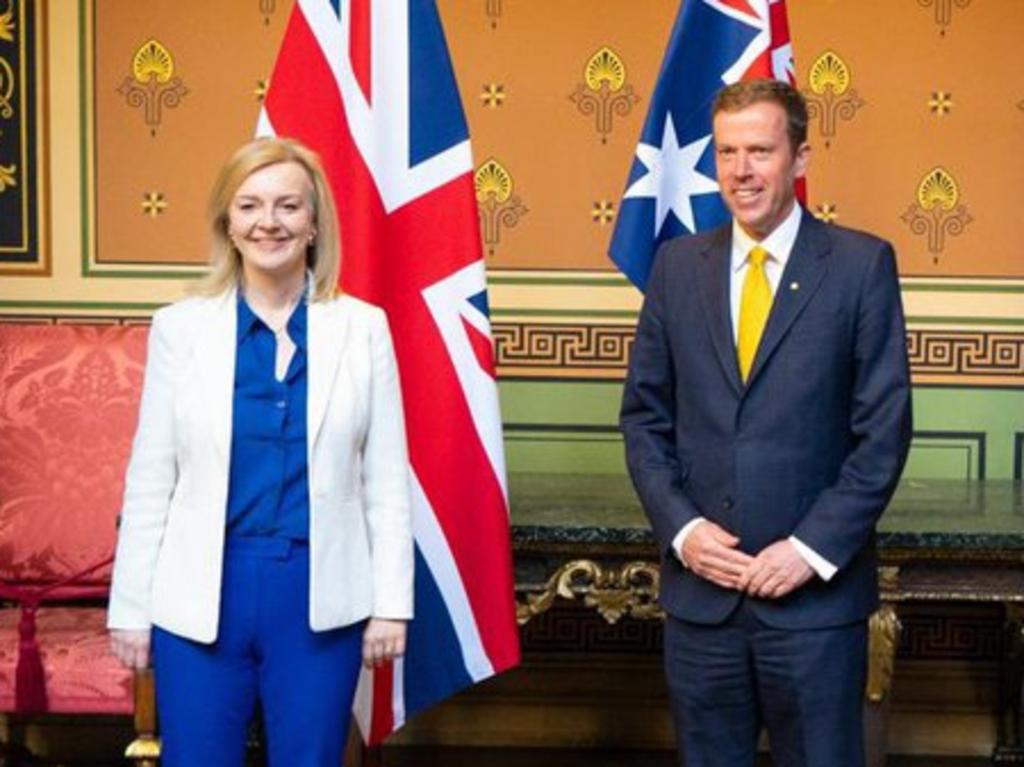

Josh Frydenberg and opposition Treasury spokesman Jim Chalmers both welcomed the largely symbolic but still significant deal in London, which paved the way for a similar agreement at the Group of 20 meeting of finance ministers next month in Venice.

The Treasurer said G7 nations had committed to “agree a globally consistent approach to the tax challenges posed by the digitalisation of the economy”.

“Australia will remain an active and constructive participant in these OECD-led discussions, as we have done so throughout,” he said.

Dr Chalmers hailed “the Biden administration’s leadership and willingness to work with other major economies to make the taxation of multinational companies fairer and more transparent”.

Facebook at the weekend called the agreement “important progress” and said it could leave the social network “paying more tax, and in different places”.

The G7 forum includes the US, Britain, Japan, Germany, France, Canada and Italy.

KPMG lead tax partner Grant Wardell-Johnson said the agreement represented a “very, very significant step”.

“It will change the international tax rules significantly,” he said.

Melbourne University tax professor Miranda Stewart said Australia stood to benefit in several ways from the proposals, although she noted it was “just the beginning” of a process that would eventually require the OECD to beat out the details to include in a final report that could be a year away.

“This is a political intervention, but an important one because both Europe and the US are at the table” after being at “loggerheads” under the previous Trump administration, Professor Stewart said.

The first “pillar” of the reforms, in the OECD jargon, focuses on reallocating profits by large global companies – perhaps the 100 biggest by revenue – to countries where those profits are made, even though the firm may not have a “taxable presence” in that jurisdiction.

The second pillar is a global minimum tax rate for big multinationals, which the G7 agreement suggested as 15 per cent.

Mr Wardell-Johnson said if implemented, pillars one and two could raise about $100 billion in revenue for governments around the world. A global approach to taxing digital services would also prevent the proliferation of unilateral measures, he said.

Professor Stewart said while Australia was not a very big market, “we do have 25 million consumers who are highly digitised and big consumers of large companies’ services, digital and otherwise”.

“It could be hundreds of millions in additional tax revenue, but in relation to the size of our budget, it’s still not a massive amount,” she said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout