George Pell: Triumph, disaster and the fearless disciple

George Pell’s life reflected his episcopal motto ‘Be Not Afraid’. Thousands around the world, who appreciated his brave faith will be praying for his soul.

George Pell

June 8, 1941 – January 10, 2023

Archbishop of Melbourne, 1996-2001; Archbishop of Sydney 2001-2014; Vatican prefect for the Secretariat for Economy, 2014.

–

Poetry lover that he was, it would not surprise George Pell that his friends recognised parallels between his extraordinary life of highs and lows and the essence of Rudyard Kipling’s “If’’.

“If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster

And treat those two impostors just the same;

… Or watch the things you gave your life to, broken,

And stoop and build ’em up with worn-out tools

If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you,

But make allowance for their doubting too;

If you can wait and not be tired by waiting,

Or being lied about, don’t deal in lies,

Or being hated, don’t give way to hating.

… Or walk with Kings — nor lose the common touch”.

At least six decades of George Pell’s life, from early 1960 when he entered Corpus Christ Seminary, Werribee, in Melbourne’s southwest to study for the priesthood, were shaped by the doctrine of the Christian feast on which he was born. That was Trinity Sunday, June 8, 1941. His father, George Arthur Pell, a gold mine manager in Ballarat and a former surf lifesaver and heavyweight boxer, was Anglican. His mother, Margaret Lillian (known as Lill) was a devoted Catholic of Irish descent. The couple’s first born children, a twin boy and girl, had died as babies the year before. Pell’s sister Margaret and his brother David followed a few years after George.

The young George Pell was a clever student, a prodigious reader and a leading sportsman – initially at the Loreto Convent, Ballarat, and from Year 5, at St Patrick’s Christian Brothers College, where he revelled in the tough, competitive atmosphere competing in sprinting, the long jump, shot putting, cricket, tennis and swimmer. But the only game that really counted for him and many of his peers, was Australian rules. In Year 10, he made the first XVIII as ruckman. By then, the Pells were running a pub, where he learned the common touch behind the bar.

After graduating in Year 12, Pell signed to play for the Richmond Tigers, the VFL/AFL team he supported for the rest of his life, eventually as club patron. The Tigers’ premiership in 2017, after a 37 year drought, was one of the bright spots in one of the hardest years of Pell’s life. He stuck with them and they stuck with them during his rise through church ranks and amid the unsavoury allegations that saw him tried in the Victorian County Court in 2018, at the age of 77, for alleged child sexual abuse offences from decades earlier. The first trial, on two unlikely counts of abuse in St Patrick’s Cathedral after Sunday Mass in 1996, ended in September 2018 when the judge dismissed the jury that was unable to reach a verdict.

Had Pell fulfilled his early ambitions to study law or medicine at Melbourne University he would have played for Richmond; in the event, he played at the seminary, which he joined in March 1960. From there, in his fourth year, he was sent to the Pontifical Urban University in Rome, a sign he had been earmarked for church leadership.

After his ordination in St Peter’s Basilica on Friday, December 16 1966 Pell completed another year of study in Rome to earn his Licentiate, coming 5th in a class of 50 students from across the world. After spending the summer of 1967 working in a parish in Baltimore in the US where he made friends with George Weigel, who decades later became the definitive biographer of Saint John Paul II, Pell moved to the Jesuit-run Campion Hall, Oxford. There he wrote his doctorate in church history on early church fathers including Clement, Cyprian, Irenaeus, Origen and Tertullian. From rugby and rowing to listening to and occasionally debating visiting speakers, Pell relished Oxford life. The college masters were struck by his dedication to parish work, above and beyond the call of duty.

Back in Australia in 1971 Pell was posted to serve as a curate in the parish of Swan Hill on the Murray River, at the centre of the wheat and fruit growing Mallee district. After fuming, initially, that such an appointment “could only happen in Communist China’’, he later regarded the pastoral experience he gained as “one of the best things that ever happened to me’’. The people of the lively, hospitable parish welcomed him warmly. He made lifelong friends. It was there that Pell published the first of numerous books – an account of 50 years work by the Sisters of St Joseph in Swan Hill.

His next appointment, in 1973, took him home to Ballarat, to the large parish of St Alipius in Ballarat East, which had five schools. It was served by four priests. It was an appointment that was to dog Pell for decades. It was his misfortune, for 12 months, to share the presbytery with the later-notorious child abuser, Father Gerald Ridsdale, who was eventually jailed in 1994. The two had limited contact.

Pell was appointed the Ballarat diocese’s Vicar for Education and principal of the Catholic Teachers college, Aquinas College, in November 1973, a job that took him to Melbourne one or two days a week.

That job was the beginning of his decades-long immersion in education, a subject in which he completed a part time Masters Degree at Monash University in 1982. Building on his experience leading Aquinas College, he played a pivotal role in the establishment of the multi-campus Australian Catholic University in the late 1980s. By that time Pell was an auxiliary bishop to Archbishop Frank Little in Melbourne. When ACU opened in 1991, the then-Bishop Pell was its inaugural pro-Chancellor. Two decades later, as Archbishop of Sydney, Pell helped establish the Sydney campus of the University of Notre Dame in the inner suburb of Broadway, which included Australia’s first Catholic medical school.

After 11 years at the helm of the Aquinas college in Ballarat and five years editing Light, the Ballarat diocesan newspaper, Pell left his home city in 1984 to take up the post of rector of Corpus Christi seminary in Melbourne – the training ground for the future priests of not only Melbourne but of regional Victoria and Tasmania. It was there, for the first time, that he ran into ecclesial controversy. His efforts to instil greater discipline, including attendance at morning Mass and better study habits, drew hostility from students and staff who preferred a less structured, less formal regime. A couple of the senior students, however, later became some of his closest lifelong friends.

The ever-increasing chasm between the traditional and liberal factions in the Catholic Church was becoming evident. Pell had the toughness and determination to prevail in what he called “a few small changes’’. It was clear to him, however, that more extensive seminary reform could only come from the bishops who had ultimate responsibility for priests’ training. That opportunity was later to come his way.

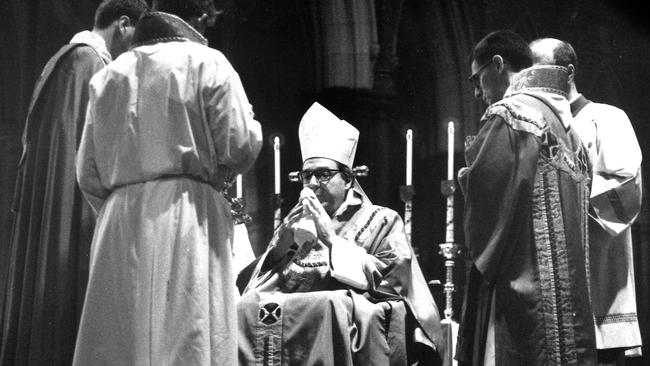

After three years running the seminary, Pell was consecrated a bishop, at the young age of 45, in St Patrick’s Cathedral on May 21 1987, a promotion that took his career, literally, out into the world, in unforeseen directions. Shortly after his consecration, Pell was elected by his fellow bishops to chair Australian Catholic Relief – the church’s overseas aid agency. For nine years, that position took up at least a day a week. It also involved frequent trips to the world’s trouble spots and poorest areas. His diaries from those trips made compelling reading, covering three visits to India, including one after the 1993 earthquake 400km southeast of Mumbai in which as many as 60,000 people perished. He wrote in his diary: “Wondered how God allowed earthquakes (perhaps God not all powerful, even cosmologically) … May God help victims and my weak faith’’.

He spent three visits working extensively in Cambodia as it rebuilt from the rubble of Pol Pot’s Killing Fields, and took active roles in Zambia, Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia and the Philippines. Distribution of aid from Australian Catholics needed extensive reform in the Philippines after the infiltration of local agencies by political operatives with Communist agendas.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s Pell and another priest made three visits, incognito, to China, encountering the persecuted underground church loyal to John Paul II, and the state — sanctioned Patriotic Association. His main mission was to assist the underground church, although he also mixed freely with many in the Patriotic Association who wanted to co-operate with Rome.

The biggest appointment of Pell’s years as an auxiliary bishop came from the Vatican. In 1990, he received “the biggest surprise of my life’’ – a message from John Paul II telling him he wished him to join the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith – the Church’s main body defending faith and morals, led by the scholarly German cardinal Joseph Ratzinger. Pell, 49, was the first Australian to join it. The Congregation’s 23 members, selected for their intellectual and theological stature rather than geographically, met several times a year in the former Palace of the Holy Inquisition, beside St Peter’s. In preparation, they studied case notes, and provided their advice to Cardinal Ratzinger. Since its foundation in 1542, the body’s duty has been to defend the Church from heresy. Pell served on the Congregation until 2000. He later served on numerous other Vatican bodies, including the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments.

After his installation as Archbishop of Melbourne on a chilly August night in 1996 at Melbourne’s Exhibition Building (St Patrick’s Cathedral was closed for restoration), Pell’s five years leading Australia’s largest archdiocese were ones of building, innovating and controversy. Most of his legacy remains intact. Pell moved Corpus Christi Seminary into the old parish buildings at inner-suburban Carlton and transferred the Australian Catholic University into the same area. He created the sculpture garden and Pilgrim Path with cascading water in the cathedral grounds, commissioned the statue of his predecessor and hero Archbishop Daniel Mannix and bought and restored the site of the birthplace of Mary MacKillop in Brunswick Street Fitzroy as a centre for families of drug addicts. Education remained his passion, which led to production of “To Know, Worship and Love”, a series of illustrated religious education textbooks from kindergarten to senior secondary school. They are in use throughout much of the nation.

In view of the allegations of sexual abuse against him that surfaced two decades later when Pell was in his mid-70s, it is ironic that within weeks of his promotion as archbishop, he established one of the first formal church processes in the world for dealing with child sexual abuse. The Melbourne Response, headed by an independent Queen’s Counsel, was described by victim support group Broken Rites as “the best of a bad lot’’.

As archbishop, Pell emerged as an outspoken, controversial figure in the national conversation. A “political agnostic’’ – in his time he voted Liberal, National and Labor – he waded into debate on issues relevant to the church. He was an outspoken critic of Pauline Hanson’s One Nation, which he condemned in 1998 for “racist policies’’ that “are a recipe for strife and misery’’ and for setting “groups of Australians against one another’’. He was a forceful critic of the Kennett government’s encouragement of gambling in Victoria. Recognising the sharp delineation between church and state, however, he infuriated the Left in 1998 arguing that John Howard’s proposed Goods and Services Tax was not an issue on which the Church could or should present a single viewpoint. Pell’s support for an Australian republic was a personal rather than a Catholic view.

He was most assertive on issues pertaining to the Christian faith, such as the National Gallery of Victoria’s exhibition of US artist Andres Serrano’s outrageous photograph, “Piss Christ”, showing a crucifix immersed in a jar of urine. The gallery, Pell argued “should be a temple of beauty; not a home for sleaze’’. He organised widespread protests against the work, winning 93 per cent public support for his stance in a newspaper phone-in poll.

Pell was also the main target of the contentious “Rainbow Sash’’ protests, refusing to distribute holy communion in his Cathedral to homosexual activists and their families and supporters wearing rainbow sashes. The issue attracted widespread adverse publicity, and defined Pell, in many minds, as an ultraconservative. But the issue was less divisive in Catholic ranks. Other church leaders of the time attested they would and did take the same stand.

Pell’s preparedness to be “the salt of the earth, not the sugar or artificial sweetener’’ as he put it prompted John Paul II, in 2001, to promote the seventh archbishop of Melbourne to be the eighth Archbishop of Sydney – a transition not made previously.

After his installation in St Mary’s Cathedral, Pell, led the Sydney Archdiocese with a conviction captured by GK Chesterton in his 1908 book, “Orthodoxy”. Catholic orthodoxy, Chesterton wrote, never took the tame course or accepted conventions. It was easier but not always right, Pell concurred, to let the age have its head; the difficult thing was to keep one’s own.

As in Melbourne, faith education, establishing university chaplaincies, seminary reform and building up vocations to the priesthood were his priorities. For 13 years, his weekly column in Sydney’s Sunday Telegraph newspaper drew a vast readership. From August to October 2002 Pell stood aside after a complaint he had abused a young boy 40 years earlier at a church camp on Phillip Island in 1961, when Pell was a 19 year-old seminarian. The matter was investigated by a retired Victorian Supreme Court judge. Pell was cleared, although the judge said he believed both Pell and the complainant. Pell returned to work immediately, offering Mass in St Mary’s for the victims of the first Bali bombing.

In October 2003, Pell was promoted to cardinal by John Paul II. He celebrated the honour with 50 friends and family who travelled to Rome from Australia, the US, Canada, England and Ireland. It was, he recalled afterwards in his weekly Sunday Telegraph column, an exceptionally happy week of partying, perhaps “a slight taste of Heaven’’. Pell was a prodigious writer, of journal articles, columns and sermons; his works were collated into several books including “Be Not Afraid”, “Test Everything” and “God and Caesar”.

He chalked up another highlight during another extraordinary week, five years later, in 2008, when as part of World Youth Day, 500,000 young people aged 16 to 30, from 200 countries, converged on Sydney, with hundreds of thousands more from around Australia, for a Saturday night vigil and Sunday Mass with Pope Benedict XVI at Randwick Racecourse. The young pilgrims were accompanied by 600 bishops and cardinals and the event was covered by 6000 journalists.

Amid the hype, Pell delivered what he regarded as one of the sermons of his life, among thousands. At the opening Mass on Tuesday July 15 at the Barangaroo site, beside Sydney Harbour, he singled out the struggling sheep, anyone normally left behind, “who regards himself or herself as lost, in deep distress, with hope diminished or even exhausted … Young or old, woman or man, Christ is still calling those who are suffering to come to him for healing, as he has done for 2000 years. The causes of the wounds are secondary, whether they be drugs or alcohol, family breakups, the lusts of the flesh, loneliness or a death.’’

Wearing the pectoral cross and ring of the first Archbishop of Sydney, English-born Bede Polding, and carrying the crozier of Cardinal Moran, the first Irish-born Archbishop of Sydney, Pell urged those present not to spend their life ``sitting on the fence, keeping your options open, because only commitments bring fulfilment’’. He addressed pilgrims in the European languages he spoke well — Italian, French, German and Spanish. In the same year Pell won the “Grand Prix Mysterium Vitae” established by the Archdiocese of Seoul in South Korea and presented annually to “an international personality who stands out for their support for the cause of life.”

Two of Pell’s most enduring international achievements date from his years as Archbishop of Sydney. In 2013, after nine years chairing the Vox Clara (clear voice) committee to oversee a new English translation of the Mass, to which he was appointed by John Paul II, Pell brought the project to fruition. Forty years after the Second Vatican Council, which had ushered in liturgies in the vernacular rather than the traditional Latin, the aim of the project was to reassert Catholic doctrines and beliefs through a more formal Mass text. “In praying to the omnipotent God at Mass’’, Pell told The Australian, “it is not appropriate to `talk in the same way we do at a barbecue’.’’

The final texts produced by Vox Clara were scrutinised and approved twice by bishops’ conferences from the US, Canada, Australia, Britain, Ireland, India, Africa and the Caribbean. For Pell personally, the endeavour involved chairing all 20 meetings in the Eternal City, studying thousands of pages and clocking up more than 650,000km in flights to and from the Eternal City. On one trip, in 2010, Pell collapsed shortly after arriving in Rome and was rushed to hospital, where a pacemaker was fitted. Within a week, he was back at work, chairing Vox Clara meetings at the North American College near the Vatican.

In October 2013 another of Pell’s long term projects came to fruition when Benedict XVI opened Domus Australia on central Rome’s Via Cernaia, a “home away from home’’ for Australians of all faiths and none. The centre operates as a four-star hotel with 35 single, double and triple airconditioned bedrooms, a chapel for 200, conference facilities, a restaurant and roof garden was built on the site of a 19th-century Marist monastery. During the excavation process, Roman flooring and pipes from the first century were uncovered underneath the construction.

The chapel, restored by Pell’s friend, Melbourne priest Charles Portelli, features paintings by Sydney artist Paul Newton of pioneers of the Church in Australia such as Caroline Chisholm, John Therry, St Mary MacKillop and founder of the archdiocese of Sydney, Bede Polding. Cardinal Pell’s coat of arms is embedded on the wall of the Sanctuary. The project, built after the global financial crisis for about $30 million, was funded by Australian Catholics, primarily those of the archdioceses of Sydney, Melbourne, Perth and the diocese of Lismore in northern NSW. It quickly made its mark as a self-supporting business, and is often booked out due to its popularity among Europeans as well as Australians.

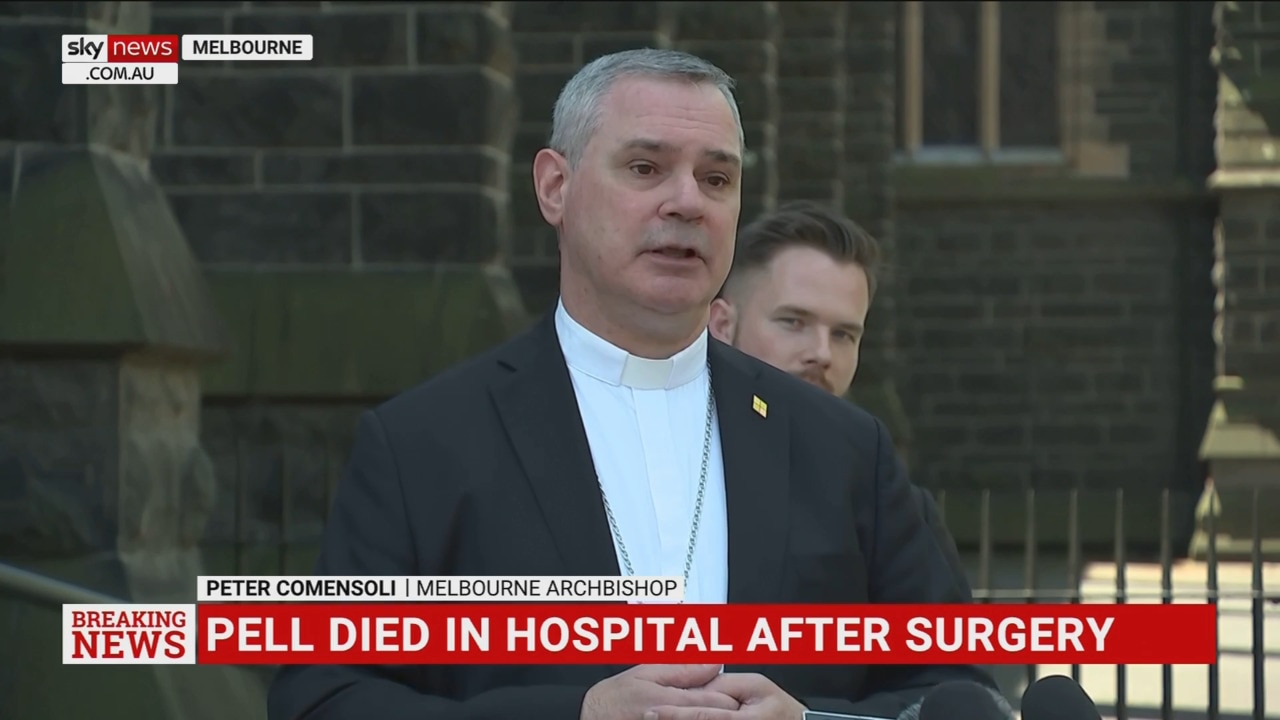

Despite the cardinal’s long history of heart disease, for which he received a pacemaker in Rome more than a decade ago, his death, from a cardiac arrest after a hip replacement operation in the Salvator Mundi hospital, was a shock. He had recently been working in Rome, meeting groups of students from Australia and seminarians from the US, and only days before had attended the funeral of his treasured friend Emeritus Pope Benedict XVI. In the lead up to the late Pope’s funeral he was also in demand for interviews from US, British and Australian media and was busy networking with brother cardinals who travelled to Rome for Benedict’s funeral. He was the author of the obituary for Benedict published in this newspaper.

Close friends said he was in the best form they had seen him for years, after he emerged from 13 months imprisonment, mainly in solitary confinement, in Victorian jails, on historic sex abuse charges dating back to his first few months as Archbishop of Melbourne, in 1996.

The Cardinal was released from jail in the lead-up to Easter in 2020 after the High Court, by a 7-nil margin, quashed the five convictions, which were made, originally, on the testimony of a single complainant. The full story of what was behind the charges, and others that were subsequently dropped by the Victorian legal system, is yet to emerge. His three, candid prison diaries, written during his ordeal, are a testament to his sense of justice, his strength and his faith. Throughout the ordeal, he never lost heart but worked with his legal teams to clear his name.

At the time of his arrest on those charges, he was serving as prefect for the Economy in Rome, essentially the Vatican treasurer, after being appointed by Pope Francis in 2014 to clean up the Vatican’s arcane and corrupt financial affairs. The mess he uncovered was unbelievable, including 80 valuable properties in and around Rome, owned by the Canons of St Peter’s, a select group of priests who sing Masses and other services at the Vatican, that had “fallen off the list’’ and were unaccounted for, not earning rent. Millions of euros, rightly belonging to charities, the poor and hospitals, had been hived off and disappeared. Hundreds of people held Vatican Bank accounts which they were not entitled to open. On his watch, 4000 Vatican Bank accounts of individuals and organisations not entitled to them were closed; 200 were referred to authorities on suspicion of money laundering. Prosecutions were launched, and scandals uncovered, such that involving the former Vatican Secretary of State, Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone, who reportedly transferred €15 million from the Vatican Bank to a private film company and used $US300,000 from a fund for sick children to rebuild his lavish apartment.

The process was often two steps forward and one back with senior figures such as Vatican Archbishop Angelo Becciu, the deputy to Secretary of State Cardinal Parolin, suspending an external audit by PricewaterhouseCoopers. The firm had been engaged by Pell to improve the transparency of Vatican finances to international anti-money-laundering standards. When Becciu was transferred to run the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, Pell provided a glimpse of the wry humour he rarely showed in public but which his friends loved: “That’s a great move, Saints has no clout.’’

The job was a rocky road, during which he was saddened by the entrenched resistance he met from brother bishops, cardinals and others, to imposing modern accounting practices and audits. At the time of his death, he was eagerly following the so-called ‘’trial of the century’’ involving cases of alleged financial wrongdoing in the Vatican.

After his exoneration, the Cardinal successfully rebuilt his life, both in Australia and Rome, suffering the loss of his beloved sister, Margaret, in December 2021. A devoted family man, he is survived by his brother, David, his nieces and nephews and their children. Despite its foibles, Pell lived for the Church and its founder. His life reflected his episcopal motto “Be Not Afraid’’. Thousands of people around the world, who appreciated his brave faith, will be praying for his soul.

Tess Livingstone is the author of the biography: George Pell: Defender of the Faith Down Under.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout