William Tyrrell: Gary Jubelin says commander told him ‘nobody cares’ about missing boy

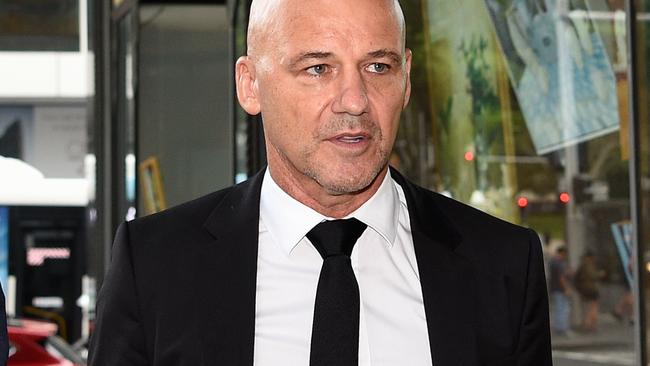

Gary Jubelin says a commander told him to drop investigation into the missing boy.

“Nobody cares about that kid.”

That is what the former homicide detective, Gary Jubelin, says he was told, three years into the frustrating investigation into the disappearance of the missing foster child, William Tyrrell.

“Get him off the books. Send him to unsolved homicide.”

Mr Jubelin, who was testifying in his own defence at the Downing Centre local court in Sydney, credited the remarks to the former NSW homicide commander, now assistant commissioner Scott Cook.

Mr Jubelin told the court he was shocked, and told his boss: “People do care about him.”

The NSW Police Commissioner tried through legal representatives to have the remarks suppressed, but the application failed in the Downing Centre local court.

The court was later told hat Mr Cook “emphatically denied” making such a statement.

NSW Police Commissioner Mick Fuller last night released a statement saying he had “full confidence in the professionalism of Assistant Commissioner Scott Cook, who has more than 31 years of exemplary service within the NSW Police Force, which includes receiving The Australian Police Meal in 2019.”

He said Mr Cook had “exemplified the definition of leader” during his time at homicide.

Mr Jubelin is on trial in the Downing Centre local court over charges related to his handling of the investigation into William’s disappearance from the village of Kendall on 12 September 2014.

He is accused of recording four conversations without the necessary warrants.

He made his long-awaited appearance on the stand yesterday, and came out swinging, saying the investigation had never been given appropriate resources.

He said it was bedevilled by equipment failure as well as a shortage of personnel, many of whom were “burnt” out by the maddening frustration of having no witnesses, no forensics, no DNA, and no real idea what had happened to William.

Mr Jubelin said the conversation took place shortly after Mr Cook became his boss.

He said he used to have a pole next to his desk at police headquarters in Parramatta, with William’s photograph fixed to it.

He said Mr Cook wandered past, saw the photograph and said: “Nobody cares about that kid” and then: “Get him off the books. Send him to unsolved homicide.”

Two other witnesses at Mr Jubelin’s trial, which has now been going eight days, have recounted to the court that Mr Cook said things like “They’ll never get anyone” for William’s murder, or else: “That case can’t be solved.”

Mr Jubelin said he had decided to target for surveillance an elderly neighbour, Mr Paul Savage, 75, who lived across the road from the house William disappeared from, after other leads had run dry.

Mr Jubelin told the court he went to visit Mr Savage on 2 and 3 May 2018 to tell him “the reasons why I thought he might be involved” in William’s disappearance.

Jubelin recorded two conversations over those two days, plus two more conversations with Mr Savage, and agrees that he did not have a valid warrant to do so, as required under the Surveillance Devices Act.

Mr Jubelin told the court that Mr Savage was under police surveillance, and there were “listening devices” in his house, and on his phones, as well as in bushes around the house, but they often failed.

“You could never guarantee they were going to work,” Mr Jubelin said.

He said he went to see Mr Savage on 2 May 2018 as part of a strategy designed to rattle him.

“I had surveillance police in the bush around the house,” he said, in part because he thought Mr Savage would be suitably shaken by the conversation that he would then “head into the bush” toward “William Tyrrell’s remains.”

He was hoping to prompt or encourage him “to go and interfere with William’s remains,” he said.

He recorded the conservation, because “there was significant amount of pressure being applied to Mr Savage ... I was concerned about his well-being. Most definitely.

“There was a possibility, given the fact that his wife had recently passed away, suicide wasn’t extreme … I was concerned about that as well.”

Mr Jubelin said he “made no secret” of the visit to colleagues.

“Everyone was aware I was going there to stir him up. That’s why we had surveillance police up there. I felt I needed to protect myself,” he said.

He recorded another conversation on 3 May 2018.

“I knocked on the front door but I didn’t get past the front door,” he said, adding: “I had the same concerns as I had the previous day. There was a degree of hostility toward me ... I’m pushing buttons. I’m poking him.”

There has been no evidence to link Mr Savage to the crime. He has never been charged and vehemently denies wrongdoing.

Mr Jubelin said there was one senior detective who thought William’s foster parents might be involved in the boy’s disappearance,

“I respect her opinion. It wasn’t what I considered (likely). I agreed to explore it with her,” he said.

“I think William’s family, biological and foster, have suffered enough. I’ve eliminated them, but that’s something for the Coroner.”

He said he saw Mr Savage again on 28 December 2018. He was on annual leave at the time, visiting his widowed mum, not far from Kendall, when Mr Savage called him on the mobile telephone.

“It was unexpected,” he said. “He had an issue with his car, which had been seized. He reached out to me.”

Mr Jubelin thought maybe this “was developing the rapport that we need. I thought, I can’t bypass this opportunity,” he said.

He borrowed his Mum’s car to drive to Mr Savage’s house. He recorded the conversation because he was alone, and “when opportunities present themselves, you either take it or you lose the opportunity.”

“If I went into his place on my annual leave ... all sorts of allegations could be made,” he said.

Mr Jubelin said he was not armed.

“I had told him I suspected his involvement in William’s disappearance,’ he said.

“Worst case scenario, Mr Savage potentially killed himself or self-harmed, it would leave me very vulnerable.”

The trial is continuing.