From western Sydney to a Syrian warzone: What happened to Yusuf Zahab?

What happened to Yusuf Zahab, the smiling boy from Sydney taken into Syria and a jail without charge, is a mystery and an international embarrassment.

January 26. Australia Day. A public holiday, and a day spent by many gathered around a barbecue, at the beach, watching the fireworks, or just hanging out with family and friends.

On the other side of the world, one young Australian spent the day fighting for his life.

“They want us to surrender now to the new prison … 10 by 10,’’ Yusuf Zahab, 17, said in a garbled voice message to his family, sent on a smuggled phone from a Syrian jail.

“I don’t know what’s going to happen, this will probably be the last time I’m going to call you, give salams to my mum.’’ He told them if they couldn’t find him, to look for him next door.

The message, received at 9.26pm Australian time that night, was, as Yusuf predicted, the last time his family would hear from him. They didn’t find him next door. Yusuf is now officially missing, and almost certainly dead.

What happened to him is both a tragic mystery and an international embarrassment which has put pressure on Australian authorities who knew he’d been held in a jail without charge for three years, but refused to take him back.

The Australian travelled to Hasakah, the city in northeastern Syria where Yusuf was last seen, to try to find out what happened to the boy who spent the first 10 years of his life in western Sydney, and what is likely the last seven years of his life in a war zone and a jail.

The rise of Islamic state

Rojava is a Kurdish word that means sunset, or the west. It’s the area of northeastern Syria that forms the western edge of the region claimed as Kurdistan, a long-disputed area which takes in parts of Syria, Iraq, Iran and Turkey. Ethnically diverse, it has a majority Kurdish population but is home to populations of Yazidis, Assyrians, Arabs, Christians and Armenians.

Since 2012, Rojava been governed by the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES), backed up by its military, the Syrian Democratic Forces. While the Assad regime in Damascus is still recognised as the official government of Syria, many foreign governments have quasi-official relationships with AANES, mostly through its urbane foreign minister Dr Abdulkarim Omar.

When civil war erupted in Syria in 2011, a number of hard line Islamist groups emerged into the power vacuum that opened up. The most powerful of these was a group which became known as Islamic State, which had been around since the al-Qaida days in Iraq in the early 2000s, but shocked the world with its rapid rise from 2013.

At its peak in 2015, Islamic State controlled vast swathes of land across Syria and Iraq, had taken the cities of Raqqa and Mosul as headquarters, and had millions of people under its control, enforcing power through brutal and primitive rules and executions.

Tens of thousands of foreigners came to Syria and Iraq to support the terror group during its prime. Among them were around 400 Australians, men who came to fight or provide other support to the terror group, women and children. Among them were the Zahab family from Australia.

‘Family holiday to Lebanon’

Aminah and Hicham Zahab had four children – older sons Muhammed and Khaled, daughter Sumaya, and the baby of the family, Yusuf. They lived what appeared to be a fairly ordinary life in western Sydney, and Yusuf rode his bike around the suburb they lived in, Condell Park. But in 2015, the family sold their home and disappeared, claiming they were going on a family holiday to Lebanon.

It later emerged that Muhammad Zahab, a charismatic maths teacher, had become one of Australia’s most powerful Islamic State members, responsible for luring up to 20 members of his family to Syria, including all members of his immediate family. He also married five times and fathered 13 children.

The family patriarch Hicham Zahab said he had taken his family into Syria innocently, to try to extract his “brainwashed’’ older sons. He denied supporting Islamic State and said he had tried to work as a mechanic after being unable to leave Raqqa.

Authorities didn’t believe him. He was charged in absentia by Kuwait over an Islamic State plot to buy weapons including missiles on behalf of Islamic State, and a cousin of his was charged and convicted in Australia.

The NSW Supreme Court ordered about half of the $1 million sale proceeds of the Zahab house to be forfeited after the Australian Federal Police successfully argued the money was being remitted overseas to benefit Islamic State. The other $500,000 was never found.

Muhammad was later killed in an air strike, as was Khaled, while Hicham is believed to have died from tuberculosis in the same prison system where his youngest son also likely died. Yusuf was 11 years old when he was taken into the Syrian war zone.

Regardless of any alleged crimes committed by any adult members of his family, Yusuf was an innocent child. He spent what seems to be the last three years of his life in jail, despite never being accused of a crime.

‘Cubs of the caliphate’

By March 2019, Islamic State was on its final legs. The Global Coalition against Daesh, the anti-IS alliance of 85 countries led by the United States, and including Australia, had almost destroyed the group militarily. The final few thousand members and their families had been driven by the Syrian Democratic Forces into a tiny pocket of land at Baghouz, a village in eastern Syria. In the final bloody days of its last stand, thousands of fighters and their families surrendered, and handed themselves in to the SDF.

They were taken on trucks and buses further north, where an underfunded, ill-equipped SDF found itself having to house more than 100,000 Islamic State fighters and their families in jails and camps across the region.

The women and children were mainly housed in two camps originally set up for refugees – al-Hol, or al-Hawl, near the city of Hasakah, and al-Roj, close to the Iraqi border. They were secured as detention centres for the families of Islamic State.

The men were detained in 27 prisons across the region, mainly in and around Hasakah, the largest city in Rojava. The sheer numbers were overwhelming, and the SDF commandeered schools and other institutional buildings to house the men from the brutal terror group who had spent the previous six years murdering the Kurds and their allies. They were reluctant jailers.

Hicham Zahab went to prison.

The Zahab women, Aminah and Sumaya, were taken first to al-Hol, and later to al-Roj camp, where they remain today. Living in tents nearby with their children are Sydney women Mariam Raad and Mariam Dabboussy, the wives of Muhammad and Khaled Zahab. There are 11 Zahab grandchildren in the camp. All up, 16 Australian women and their children live in al-Roj.

None of the women have been charged with any crime, although some will likely face charges of having entered a proscribed area if they are repatriated to Australia. They have already been held for 3.5 years without charge.

Yusuf Zahab fell through the cracks. He was 14 when he surrendered with his family at Baghouz – still just a child, but deemed by the SDF to pose too much of a risk to stay in the camp with his mother because of his age. He was taken into a different line of people, and placed into a different vehicle, from the one his mother and sister were taken away in. Yusuf and around 700 adolescent boys, under the age of 18 years, were put into annexes in the men’s prisons, juvenile jails for “cubs of the caliphate’’.

IS scars raw, world turns blind eye to foreign fighters

After the fall of Baghouz, large parts of Syria lay in ruins. In Rojava, where the SDF had fought off the barbaric invaders, it became obvious that a substantial number of foreigners were among the Islamic State fighters and families who had survived to the very end.

In Australia, the previous Coalition Government wanted nothing to do with them, and the public largely agreed with that decision.

In July 2019, two groups of survivors were brought out to Australia – young children and orphans from two different family groups. Federal and state laws and suppression orders prevent the public knowing much about how those two family groups have settled in Australia, although they are thought to be settling in well. Australia has not repatriated a single man, woman or child from Syria since.

The domestic spy agency, ASIO, secretly sent officials to the region in late 2019, and determined that at least 12 men were detained in the prisons, along with around 20 women and more than 40 children in the camps.

Yusuf Zahab was counted among the men. Australian authorities knew he was there, in a youth annex at the al-Sina’a prison in Hasakah’s Gweiran neighbourhood. He turned 15, then 16 then 17 behind bars. In April this year, he would have been sent to the men’s prison with some of Islamic State’s worst and most brutal fighters. The Australian Government was unmoved by the plight of people like Yusuf in Syria.

“I think Australians would certainly support that.

“I think it’s appalling that Australians have gone and fought against our values and our way of life and peace-loving countries of the world in joining the Daesh fight, I think it’s even more despicable that they put their children in the middle of it.’’

At the time, the scars inflicted by Islamic State on the world were raw. The beheadings, tortures and murders, the attacks carried out in the west, including in Australia, meant the public had no time or sympathy for those considered to have willingly gone to Syria and joined the wicked terror group.

The Australian Government introduced laws such as temporary exclusion orders to keep would-be returnees out, and set about stripping citizenship from those deemed to be members of the group.

Five Australian children were born in the camps, and have now spent 3.5 years behind the wire. Globally, there was an understanding that keeping the families, particularly the women and children, offshore indefinitely was leading to a national security and humanitarian disaster. The United States led the way, repatriating its 28 citizens, and publicly urging other countries such as Australia to do the same.

The SDF begged for help, saying it could not continue to sustain the pressure of housing 12,000 men and more than 70,000 women and children in ill-equipped and unsafe facilities. It warned Islamic State was regrouping, and wanted to break its members out of the jails, and its families out of the camps. The global community continued to turn a blind eye.

Then, in January this year, the disaster the SDF had been warning finally struck.

IS prison attack and Yusuf’s last known moments

The Battle of Hasakah began at 7pm Syrian time on January 20 when Islamic State detonated a truck packed with explosives at the main gate of the al-Sina’a prison.

The jail, also known as Gweiran Prison, or Central Prison, has seen violence before.

Built in 1958 to house 1500 prisoners, it has previously held Kurdish detainees, and was attacked by Islamic State in 2015, with the Islamists seizing it from Damascus-backed regime forces. A year later, the Kurds captured the prison, and populated it with Islamic State detainees. It was filled to bursting point after the fall of Islamic state in Baghouz in 2019.

There were 3500 men, many of them hardened Islamic State fighters inside the jail in January, and Islamic State wanted to get some of its senior leaders out.

The explosion provided cover for around 100 heavily-armed Islamic State fighters to attack the jail from several directions. A suicide bomber on a motorcycle caused further chaos, while inside, hundreds of Islamic State fighters attacked from within. Oil tankers were set alight outside the jail, sending thick, oily smoke across the neighbourhood and into the jail, and making air strikes by the US forces stationed nearby impossible.

The prisoners escaped their packed cells and took over the jail. Previously-separated prisoners with mental illness or infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, mingled with the general population. The youth annex was breached, and Yusuf and the other juveniles were absorbed into the melee.

Over the next three days, an unknown number of Islamic State fighters escaped. Inside, there was unimaginable horror.

SDF guards were slaughtered. Islamic State took their weapons, and a number of SDF guards hostage. The green and white walls were covered in blood.

Food and water ran out. Yusuf and others drank from leaking airconditioning units.

By January 23, SDF had reinforcements in place. Up to 10,000 troops began to regain control of the outer perimeter of the jail and the neighbourhoods nearby. Inside, the prison was still an uncontrollable, murderous hellscape.

On January 24, Yusuf got access to a phone and sent messages to his cousin in Australia, Hala Zahab, trying to explain what was going. “The kids are everywhere … there’s no such thing as kids,’’ he said, meaning the young prisoners were now mingled in with the men. It’s probable the juveniles were being held by Islamic State as human shields.

Elderly and sick prisoners were exchanged for food and water. Foreign troops including United States Special Forces helped restore order on the outside. Inside, no-one knew anymore who was Islamic State and who wasn’t.

On January 26, Australia Day, Yusuf got several voice messages out of the jail using a smuggled phone which has since been disconnected. Some went to Hala in Sydney. Some went to Letta Tayler, associate director at Human Rights Watch in New York. Yusuf said he was going to surrender. He wasn’t sure why he was being asked to surrender, as he wasn’t an Islamic State fighter, but he knew he needed to leave.

“I received frantic voice messages from Yusuf around 10pm New York time on Tuesday, January 25, which would have been around dawn on Wednesday, January 26 in Hasakah,’’ Ms Tayler told The Australian.

“Shortly before that I heard from a different detainee inside al-Sina’a that some of the wounded were being evacuated but that detainees were scared to leave, even if they raised white flags, for fear they would be shot.

“I must emphasise that I have absolutely no evidence one way or the other regarding whether such fears were justified.

“Shortly after 7am New York time on January 26, which would have been early afternoon that same day in Hasakah, I received harried voice messages from that same second detainee inside al-Sina’a. This time, this second detainee told me that “they” were taking detainees to the new prison next door. He did not say who “they” were but I assume he meant the SDF. “But then he said there was further military activity with more people killed and that detainees were leaving the building, fearing that if they stayed inside they would be killed. Then the line dropped. That was the last I heard from any of the detainees.’’

What happened next to Yusuf is unknown. His family heard a rumour he might have been taken to a British-funded “Panorama’’ prison. There is no prison known as Panorama in Hasakah.

There is, however, a large roundabout called Panorama, close to several of the city’s 27 jails. Their precise locations are mostly a well-kept secret.

US Lieutenant General Paul Calvert, a Commander with the anti-ISIS Coalition, has revealed the UK provided $US20 million in funding for the prisons last year.

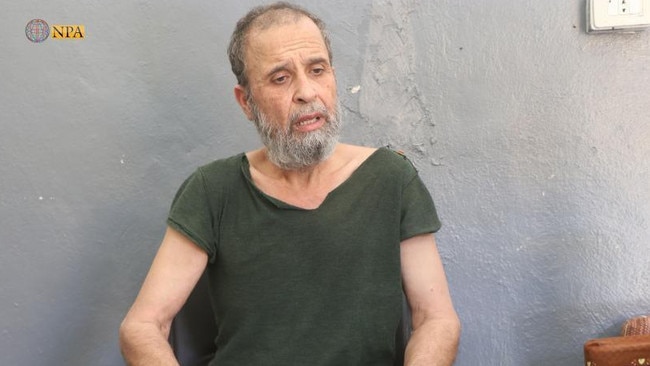

An Australian Islamic State member imprisoned in al-Sina’a prison, Hamza Elbaf, reportedly told someone he was with “Saghir Zahab’’ (the little Zahab) when the riot erupted. However, when The Australian met Elbaf in the prison in August, he said he didn’t know Yusuf Zahab.

He said his last interaction with anyone from the Zahab family was in 2019, when he shared an isolation cell with Hicham Zahab.

Rumour has it that Yusuf was hiding near the kitchen area of the prison when he decided to evacuate. The exact meaning of his message “10 by 10’’ is not known, although it may be a reference to surrendering to the SDF fighters outside in groups of 10 at a time.

Further unsubstantiated rumour has it that the British might have been outside. Yusuf was told by family through messages on that final day to turn left as he left the prison, because the British forces might be stationed to the left. He was to loudly identify himself as Australian.

It has not been confirmed the British were at Hasakah during the nine-day siege.

The Kurdish Commander-in-Chief of the Syrian Democratic Forces, General Mazloum Adbi, co-located with the Americans leading the anti-ISIS Coalition in Hasakah, would not speak to The Australian about Yusuf.

A few facts can be confirmed.

In Sydney, Hala Zahab spent the public holiday cleaning her mother’s house, who was due home from overseas the next day, and monitoring her phone for messages from Yusuf.

At 2.07pm, a photograph pinged onto her phone. It was of Yusuf, wearing a blue Adidas jacket over T-shirt, a bandage on his head and another on his arm. He was wounded, although probably only lightly, but was terrified.

It would have been sent at 6.07am Syrian time.

Then, at 9.26pm, or 12.26pm Syrian time, that final voice message from Yusuf.

“They want us to surrender now to the new prison … 10 by 10. I don’t know what’s going to happen, this will probably be the last time I’m going to call you, give salams to my mum.’’

He told them if they couldn’t find him, to look for him next door.

The voice messages were later distributed, with family approval, by Ms Tayler at Human Rights Watch.

“My name is Yusuf Hicham Zahab,’’ he says, in a message broadcast around the world. “I just got shot by an Apache (attack helicopter) … there’s no doctors here who can help me. I need help, please.’’

In the camp two hours away, Aminah Zahab heard the news, and her son’s panic-stricken voice. She wept and prayed.

Around the prison, the SDF counted the cost, and the bodies.

A total of 177 SDF troops were killed – 77 of them prison guards and 40 troops fighting outside. The SDF counted prisoners and outside Islamic State fighters together, and tallied 374. If Yusuf was among them, his name does not appear to have been recorded. The New York Times later reported seeing the bodies of two juvenile boys outside the prison, and evidence of a mass grave, with bodies taken away via excavator. No-one knows who the boys, or the bodies in the excavator, were.

‘Lost boys’ of the Kurdish prison system

In the following months, Human Rights Watch tried to find Yusuf but was unable to gain access to the prisons.

United Nations Special Rapporteur Fionnuala Ní Aoláin investigated, and discovered up to 100 “lost boys’’ have vanished within the Kurdish prison system.

In June, The Australian visited the prison in Hasakah and asked to see Yusuf, but he wasn’t produced.

In the camps, Aminah and Sumaya Zahab spoke to The Australian, begging for information.

“The last we heard from him was January,” Mrs Zahab said.

“So many organisations have been sent to see him (but) they refused to let anybody in. I’ve been worried sick.”

Sumaya said the family heard Yusuf’s pleas for help when they were broadcast on news channels in Syria.

“I heard him, he was pleading to go back home,” she said.

“The last thing we heard about him was he was injured.

“We don’t know anything since then … no one has been able to ¬locate him at all.

“Yusuf told family back home that ASIO had met with him a few months after he got there, and he told them he wanted to go back home. And they told him they’re coming back for him. And they never did.

“He’s even told family he’s been tortured. He told ASIO he’d been in solitary confinement and he wasn’t doing well and the conditions of the prison were horrific.

“He’s in a men’s prison and they did nothing about it.”

She said she just wanted to see him one more time.

“Just once. That hug. He is a victim.”

Two weeks later, Kurdish officials turned up at the al-Roj camp and asked to see Aminah Zahab. They had spent the past six months auditing the prisoners and told her they could not locate Yusuf in their system. “We don’t have him,’’ they said.

Aminah Zahab feared the worst.

By now, word had got back to the Australian law enforcement and intelligence communities. They believed Yusuf had probably died, either in the days or immediate weeks after the battle of Hasakah. A photograph of Yusuf was allegedly taken by the SDF, where the teen was wearing a brown top, similar to what the men wore in the jails. It might have been taken in February, days after the attack finally ended on January 29. But if he was still in the prison, no-one could find him.

The Australian reported on July 17 that Yusuf had most likely been killed. His devastated family held prayers for the teen at the Lakemba Mosque.

The Australian Department of Foreign Affairs made contact with the family, and the Australian Ambassador in Beirut, accredited to Syria, reached out to the autonomous administration. No trace of Yusuf emerged.

The Australian went back to Syria in August and made multiple approaches to the SDF in Qamishli, Rmelan and Hasakah seeking information about Yusuf. Finally, after two weeks, a message from the Rmelan office.

“His file has been closed.’’

Written off by officialdom

So what happened to Yusuf Hicham Zahab, the smiling boy from western Sydney taken as a child into a war zone, then into a jail?

He may have been killed on January 26 by the SDF as he fled the prison, surrendering, as he was told to “10 by 10.’’

He may have been killed shortly after that by Islamic State inmates, before he got the chance to surrender.

If he survived those final few days, he may have died days later from tuberculosis, the disease which was racing through the prison, and had already claimed the life of his father.

He may also have targeted by someone inside the prison in revenge for getting the voice-messages out to the public.

More improbably, he may still be in the system somewhere, somehow overlooked by the SDF and the aid agencies who have been trying to find him.

It is almost impossible to think he may somehow have managed to escape. If he had, he would have contacted his family.

And so the boy who never got the chance to become a man is written off by officialdom, another file closed. And his family never did get to give him that final hug.