From a yellow bloom amid the mire of Auschwitz, a blossoming of hope

It is a colour traditionally associated with cowardliness, but for twins Annetta Able and Stephanie Heller, yellow was a symbol of life.

It is a colour traditionally associated with cowardliness but for the longest time, for Annetta Able and twin sister Stephanie Heller, yellow has been a symbol of life.

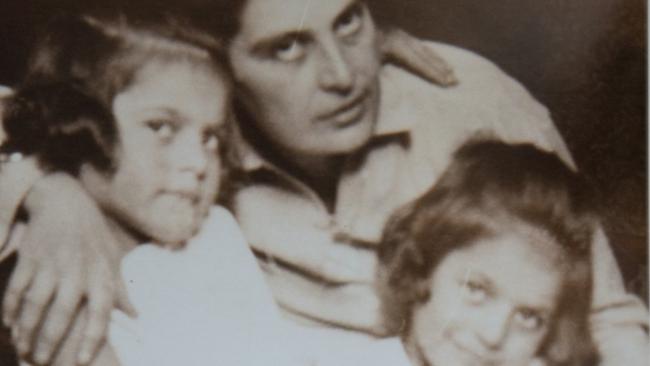

An unexpectedly long lifetime ago, when they were still in their late teens and their childhoods had been obliterated by war, they were imprisoned at the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. In December 1943, before they had even turned 20, they were among 2473 Jews unloaded at the Nazi extermination site in Poland and crudely tattooed with the five digits that would replace their identities for as long as they remained alive there.

For the longest year they were subjected to hunger, cold, exhaustion and horrendous sanitation, like all prisoners. Then, because they were twins, they endured even more.

The camp’s physician, the notorious Josef Mengele, was conducting barbaric experiments on twins, dwarfs and gypsies, and the sisters’ existence became a ghoulish amalgam of work and tests. At times they were forced to load naked corpses on to trucks. At other times they were injected and X-rayed by Mengele’s aides, undergoing measurements and gynaecological procedures, and eventually being transfused with the blood of Polish male twins, a frightening process that nearly killed them both.

Their lives were reduced to a gruesome existence measured in minutes.

“Hope in Auschwitz? In that time you didn’t think about anything. You hoped to get out alive,” Able said at our first meeting at her home in Melbourne in 2016, at the start of a series of interviews for a book on Australia’s oldest Holocaust survivors.

“We lived like a bear hibernating. It was not life. It was just surviving the day.”

Then, amid this horror, the sisters experienced a singular moment of beauty. One day in 1944, during a rare flash of sunshine, a yellow flower appeared on the ground. Amid this monochrome landscape of ugliness and misery — mud, death and leaden skies — a dandelion was miraculously growing.

“We were so happy to see it,” remembered Heller, for whom a single colourful bloom, normally dismissed as a weed, came to represent not only what the twins had lost but also what they dared hope for: a future where they, like flowers, could grow freely.

It would not be until well into the following year that they were reacquainted with freedom.

When Auschwitz-Birkenau was liberated 75 years ago, on January 27, 1945, neither twin was there.

With Russian troops advancing, they had been forced on a treacherous death march by camp officials, weak and starving and trudging through one of Europe’s coldest winters, before arriving, miraculously still alive, at another concentration camp in Germany. From there they were finally free in the spring of 1945.

“In the morning, as the SS guards vanished, we flew out of the cage like birds,” Able remembers now.

“The American soldiers put up a tent for us and two other girls, and we waited for the wings to grow to fly home to Prague to meet the family.

“We just breathed the fresh air and enjoyed nature, full of colours and smell — free.”

They would soon learn, however, that their entire family had been murdered because of their religion.

At 21, the twins had become an increasingly rare commodity: survivors of one of the most notorious Nazi concentration camps.

And in the decades that followed, they set a series of unlikely milestones: living for close to a century and creating a combined family that would span four generations and number about 30 descendants.

They even earned a spot in the Guinness World Records in 2016 when, aged 92, they were officially recognised as the world’s oldest twins to have survived Mengele.

Of all their achievements, there was one especially poignant postscript.

Both sisters would go on to live in comfortable Melbourne houses around the corner from one another, each with an expansive garden where flowers grew as freely as they did in their new lives at the other end of the world.

In September, aged 95, Heller died at her beloved suburban home, with its flower-strewn front garden on to which she would so often gaze from her kitchen.

And her bereft sister, Able, finally moved out of her own nearby house in, of all places, Freeman Street, for a retirement village in another part of Melbourne where she would be closer to her doting children.

What might she have thought, 75 years ago, if someone had predicted she would eventually be living happily in Australia, matriarch of a large, loving family, healthy, painted for the Archibald Prize, interviewed in multiple books in a language to which she was not born, and still travelling interstate at 95 to attend a grandchild’s wedding?

“I could hardly imagine how life would look tomorrow,” Able says now.

“I only hoped that life for our children would turn out to be nice, and that they would not be deprived of a family and a happy childhood like we were. And now I can say that my cup was filled.”

Everyone responds differently to adversity. To survive 75 years of freedom after several years of hell, Able forced herself to look forward.

“It’s my nature; I don’t look back on bad things. I always hope it will be better and I try and take the good things,” she said in one of our many conversations that continued long after the book interviews were completed, and we would gather for lunch with Heller in her kitchen.

Sometimes I would bring them each a bunch of yellow flowers.

Before their story, along with 16 others, was published in 2018, I visited Auschwitz-Birkenau, the living hell that has endured, in varied ways, in the lives of each of its unlikely survivors.

It was spring, still cold, with the odd flurry of snow, yet the sun shone as I entered that unimaginable place.

Almost immediately I looked down, seeking reassurance in the solid ground beneath my feet, and there was a patch of yellow.

A cluster of dandelions had burst through the muddied earth and it seemed there were perhaps 30, one for each new member of the twins’ Australian family.

In this place of death, it seemed the most exquisite symbol of life.

To those unaccustomed to the devastating impact of hate, Able has a simple message on this momentous anniversary.

“Be aware of every nice word, deed and sunshine,” she says.

“Do not hate, and try to forgive each other for little misunderstandings; it could be worse. Enjoy your family and help each other willingly and from the heart.

“Appreciate having a big family, as we did not have one (when younger), with all the lovely gatherings and friendliness — and sense of belonging.”

Fiona Harari is the author of We Are Here: Talking with Australia’s Oldest Holocaust Survivors (Scribe)