Former police Christophe Glasl officer explains why Martin Bryant was not killed at Port Arthur

A former special ops officer on duty at Port Arthur during the 1996 massacre reveals how close Martin Bryant came to being taken out — and why police wouldn’t kill him.

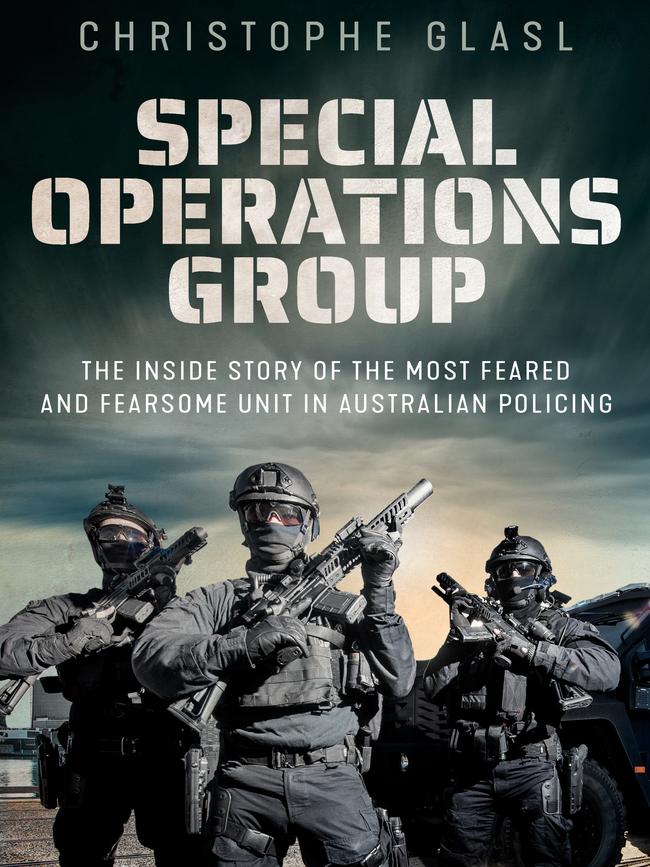

Editor’s note: Christophe Glasl’s book Special Operations Group: The Inside Story of the Most Feared and Fearsome Unit in Australian Policing has been withdrawn from sale by publisher Hachette after after Victorian Police said the author was never actually at Port Arthur.

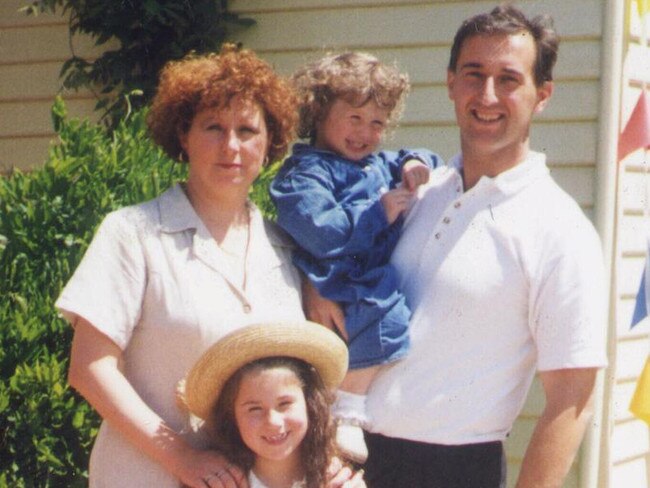

Martin Bryant had shot and killed 35 people at Port Arthur, ordering some to their knees, dragging others from their cars, firing bullets even through the backs of parents trying to shield their children.

Now he was holed up on the second storey of the nearby Seascape Cottages, and police had him in their sights. They could have shot him dead, and they did not. They brought him out alive.

It’s near impossible to imagine such an outcome today, with police far more likely to shoot on sight, but this was 1996, in every sense a different time – before September 11, before Sandy Hook, before school shootings became so bleakly commonplace.

But did police on duty that day – police who were themselves under fire, since Bryant had shot the windows of the cottage out – consider taking a sniper’s shot at Bryant? They did. A former police officer, who was part of the Special Operations Group sent to engage with him, has written about that decision in a new book, which also reveals all the other options police considered to disarm Bryant, including deafening him with the sonic boom of a RAAF jet, distracting him with exploding oil drums, and ramming him with an army tank to prevent further loss of civilian life.

Christophe Glasl joined the Special Operations Group of Victoria Police in 1994, hoping to become part of a unit that was “untouchable, indestructible and bonded”. The experience was not as he expected, but there were elements that left him feeling proud of the “most feared and fearsome unit in Australian policing”.

The decision to keep Bryant alive is one example.

Glasl explains in his book, Special Operations Group, that he was on duty on April 28, 1996, the day Bryant packed his bag with a Colt AR15 SP1 carbine 5.56mm semiautomatic rifle and an L1A1 SLR 7.62mm, both with an effective firing range of 800m, and left his house, bent on carnage.

He notes that Bryant stopped on the way to the Broad Arrow Cafe at Port Arthur and spoke with two people on the side of the road whose car had overheated.

“He suggested they come to the Port Arthur Cafe for some coffee later,” he writes. He walked into the cafe carrying his bag of weapons. He finished a meal, returned his tray, “pulled out the Colt AR15 with scope and a 30-round magazine and began shooting”.

Glasl recounts chaotic scenes: one man threw a tray at Bryant, others tried to shove women and children under the tables. Anthony Nightingale screamed, “No, not here!” but Bryant shot him in the neck. Carolyn Loughton threw herself on top of her 15-year-old daughter, Sarah, so Bryant shot her in the back, and Sarah, too.

From the cafe, Bryant strolled into the gift shop, where people were again trying to shield their loved ones with their own bodies.

“Many people were running and trying to hide,” Glasl writes. “Others thought it was just a re-enactment and actually moved towards the area.”

Bryant shot a coach driver, who crawled under his bus. He got in a car and drove toward the toll both, where he shot Nanette Mikac, three-year-old Madeline and six-year-old Alannah. On his way out to Seascape Cottages, he dragged more people from cars, and shot them. He shot at cars coming in the opposite direction, smashing their windscreens. He dragged one man from a driver’s seat and locked him in a boot.

It was 2pm by the time he got to Seascape Cottages. In the meantime, Victorian police had been alerted to the unfolding horror, and ordered on to a plane to Tasmania, to assist the local police who were struggling to cope with the mayhem.

“The brakes were smoking when we arrived,” he writes. “Continuous gunshots could be heard in the distance.”

Bryant was still firing from the top floor, and police believed that at least two, possibly three, hostages, were being held.

“Bryant had an excellent vantage point from the second storey … a walk-up assault on the premises would leave us exposed and vulnerable,” Glasl writes.

“We began thinking of other options, a tank or armoured vehicle, but nothing was available. One of the team leaders suggested a bulldozer. The members back in Victoria were even trying to have our armoured vehicle flown in, using the RAAF and their Hercules aircraft.

“Bryant was shooting relentlessly in all directions while we continued to plan. He would not present himself at any of the windows. Instead, he stood a metre back so as not to expose himself to our snipers.

“One option we considered was having the air force fly over the cottages with their F/A-18 or F-111 fighter jets and give off a sonic boom to distract Bryant … and lead an assault through the front door. A second option to distract him was detonating 44-gallon drums filled with fuel.”

The only other option was a “head shot” but the Tasmanian police commissioner did not want to give the SOG permission to shoot Bryant on sight.

“Sierra (a former member of the SOG, who cannot be identified) held the position of Sniper One at the SOG – the responsibility rested with him,” writes Glasl. “He triple-checked his Robar SR90 7.62mm Remington 700 before crawling to a position at the front of the house. He asked for permission to engage Bryant if he presented himself but that permission was denied ...

“Sierra was shocked. Bryant had killed at least 30 people but he didn’t have permission to shoot him. All Sierra could do was get in position and wait while he came under fire.”

Shortly before dawn, smoke began to seep out of the windows of the building, and fire soon had hold of the weatherboards.

“It was a totally surreal scene, flames and smoke billowing from the building, while the night sky was replaced by the rising sun and birds began singing,” says Glasl.

“Sierra radioed that he had observed a male person climbing out one of the ground-floor windows. He could see that the person was unarmed, had long blond hair and his clothes were on fire – the male person was screaming in apparent pain. Sierra once again flicked off the safety switch to his sniper rifle. His scope was set for exactly 200m. He lined up the male’s head in the centre of the crosshairs of his scope. He was not certain if it was Bryant. It could have been one of the hostages. It was only when this male ripped off his burning clothes and turned to face him that Sierra was certain it was Bryant.

“The thought of shooting Bryant crossed Sierra’s mind again. He began to squeeze the trigger of his Robar – Bryant did not deserve to live. One shot to the head and it would be all over.

“But he would not be justified taking a shot in this instance. No jury would ever convict him of murder, he was certain of that, but if he took the shot then he would be no better than Bryant himself. He was not judge, jury and executioner. His role was to remain professional and save lives. His trigger was a two-pound pull and he had a pound and a half of pressure on the trigger at that moment. Just a bit more and it would all be over. He resisted the urge to shoot.

“The arrest team then moved in and surrounded Bryant, all with guns pointed directly at him. Every single member wanted to shoot Bryant. If just one member had opened fire, then the rest of the team would have followed. He had just murdered 35 people and wasn’t about to be treated with kid gloves. The boys hit him hard during the arrest and made sure he remembered us. But Sierra looked down at Bryant and directly into his eyes, and found them empty. At that moment ... all he felt for Bryant was pity.

“Lying naked on the ground in front of them was the world’s worst mass murderer: skin peeling away; hair scorched; lifeless eyes, and no soul.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout