When the Brahman Express set sail from Wyndham Port in Western Australia’s rugged north on Thursday carrying 3500 cattle on a five-day journey to Indonesia, Andrew O’Kane felt a sense of relief.

After a tense start to the year, the manager of Carlton Hill cattle station was simply glad the live export trade that sustains the Kimberley and the property’s 30-odd staff were able to carry on.

“This is the day we’ve been waiting for,” Mr O’Kane said as the Brahman Express was loaded.

“I’m so excited to get these things on to the ship and away.”

Three months ago, the region was turned upside down when a one-in-100-year flood saturated every creek, swamp and waterhole and sent a swollen Fitzroy River surging over the only bridge connecting the Kimberley to the rest of the state. While the worst of the deluge missed Carlton Hill, in the state’s extreme northeast, the still-soggy landscape posed challenges for the station’s ringers, who began mustering mostly brahman cattle on March 12.

Fortunately, damage to roads and infrastructure around Kununurra was minimal, meaning Thursday’s shipment to Lampung could go ahead. “We were watching the forecast and making sure we had our cattle on high ground,” Mr O’Kane said. “We were worried it could have wiped out the roads between here and the port. It would have affected us a lot because we would have had to go out of Darwin at huge extra cost. We were lucky it changed course.”

The challenge came amid a nervous time for the live export industry, with a New Zealand ban coming into effect this month and the Albanese government moving to end the live sheep trade.

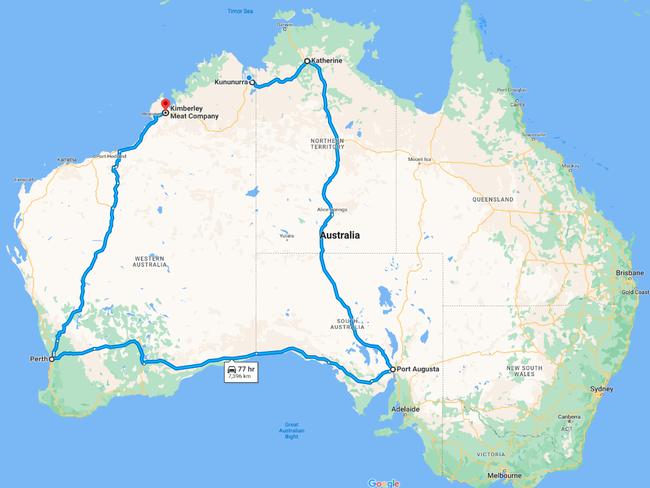

While roads from Carlton Hill to Wyndham are open, the destruction of the Fitzroy Crossing bridge on the Great Northern Highway effectively split the Kimberley in half and cut northeastern WA from the rest of the state. For the trucks that cart cattle to meat processors in the south, the only route now is the long way round via the Nullarbor.

It’s turned a 12-hour drive from Kununurra to the nearest accredited abattoir, the Kimberley Meat Company facility near Broome, into a three-day, 6000km ordeal.

The bridge is not expected to be repaired for at least a year, leaving the meatworks, which gets 80 per cent of its cattle from the East Kimberley, scrambling for stock.

KMC this week sent a shipload of cattle from Darwin to Broome, but it’s still an extra 1000km by road and 1200km by sea for east Kimberley pastoralists.

“Now you can’t send any cattle from up here to the meatworks,” Mr O’Kane said. “As a company, we’re safe from the impact because we’ve got the live exports and two feedlots in Indonesia, but I don’t know what others are going to do. Especially after the floods. This is the main livelihood here.”

Most famous for its turn as the fictional Faraway Downs in the 2008 Baz Luhrmann movie Australia, Carlton Hill bears all the hallmarks of the Kimberley. Rugged plateaus, red cliffs, swampy valleys, timbered plains filled with boab trees and pristine rivers teeming with barramundi and crocodiles cover the 475,709ha property. It’s a beautiful but rough part of the world, where temperatures remain stubbornly in the 30s and a HiLux is a “town car”.

Carlton Hill, which runs about 65,000 head, has been run by British-owned Consolidated Pastoral Company since 1992. While it is scenic and good for breeding and raising cattle, like most of the north, extreme seasons and variable soils and pasture types make it unreliable fattening country. That’s where live exports come in.

CPC’s feedlot in Lampung is closer to major beef processors on the east coast and, with a population in Indonesia of 275 million, offers a premium market for Australian cattle. Indonesian buyers, who use halal practices during slaughter, prefer live cattle to boxed beef and companies such as CPC are willing providers.

Heavier cattle on this week’s shipment will be ready for processing for Eid al-Fitr celebrations in late April marking the end of the month-long dawn-to-dusk Muslim fasting period of Ramadan.

Live exports are the driving force behind the fervent energy at the Carlton Hill homestead every morning. Before dawn, the station is bustling with its 30 staff, mostly aged under 30, eating a quick breakfast before heading off to complete the day’s jobs: mustering, feeding stock, fencing, fixing machinery, working horses, cooking, paperwork and checking water supplies.

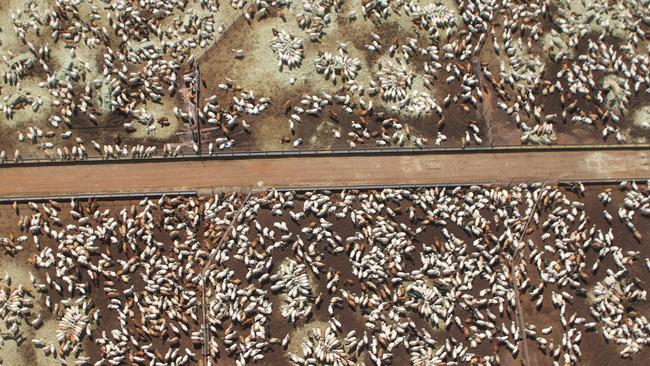

Mustering cattle for Thursday’s shipment from the vast and rugged terrain on Carlton Hill took two weeks and involved helicopters, horses, motorbikes, dogs and many nights in swags.

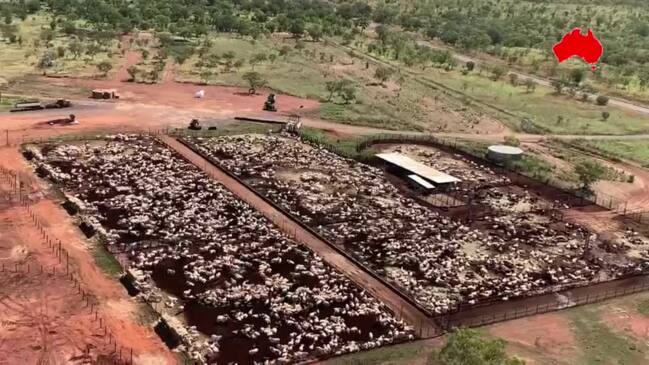

After being penned in a “cooling yard”, the 3550 cattle were herded for five days and 50km from the station to a set of holding yards, called Tri Nations.

The cattle were separated into different pens depending on their sex and weight. Horned cattle were also separated and given more space on the ship to prevent injuries.

Improved practices have led to significantly improved conditions for livestock on the ships. “We put a lot of effort into our cattle,” Mr O’Kane said. “It is our livelihood.”

The mortality rate last year on ships with CPC cattle was 0.02 per cent – less than in the paddock.

The herd is quarantined at Tri Nations for several days and fed high-protein pellets and hay equalling 2.5 per cent of their total body weight. They get the same on the ship, where they gain weight even before setting foot in an Indonesian feedlot. The cattle exported this week averaged 377kg.

Loading of the ship is dictated by the tides, which, in this part of the world, can be massive.

Fortunately, this week the tides were neap, meaning less water height difference than normal.

Still, it’s a 12 hour process involving 22 truckloads of cattle from the holding yards to the port, 100km away.

An electronic reader registers digital ear tags on the cattle at every point of the journey and again upon arrival in Indonesia where they are trucked directly to a quarantine facility at the feedlot.

The tag is also recorded at the point of slaughter, giving complete traceability to each animal.

Mr O’Kane has followed the cattle on the journey from Wyndham to the Indonesian feedlots and describes the operation, which employs 20 animal welfare officers, as a “clean, tidy show”.

While at Tri Nations, the cattle were checked by a vet contracted by the company and unwell cattle deemed unfit to travel. A government vet then verified the findings. Vets also check pen spacing, food and airflow aboard the ship. The same process takes place before every shipment.

Each year, CPC sends about six loads of cattle from Carlton Hill to Indonesia, where the company has 600 employees.

The company also loans the Tri Nations holding facilities to others wanting to export from the Wyndham port.

With the Fitzroy River bridge down, it is likely that the reduced ability to send cattle to the Kimberley Meat Company abattoir will mean greater use of the Tri Nations yards.

The man overseeing the loading of the ship, Tick Everett, from exporter Frontier International, says animal welfare is at the forefront of operation. He said the industry had vastly improved since a 2011 Four Corners report aired footage of cattle being inhumanely killed in Indonesian abattoirs. A hasty one-month shutdown of the trade by the Gillard government caused uproar among pastoralists who successfully pursued a class-action lawsuit against the government.

Frontier, which exports 150,000 cattle a year to Indonesia and Vietnam, sends about 15 ships a year out of Wyndham.

“I think we will see a lot more ships this year out of Wyndham given the situation at Fitzroy Crossing,” Mr Everett said.

“It has to be managed properly and I think we do that now,” Mr Everett said. “The trading terms are a lot different now.

“It’s a weight-based sales process and the healthier they are, the more money they make so it is in everyone’s interest for them to arrive in good condition.”

CPC also employs animal welfare staff to oversee conditions in the feedlots and during slaughter.

Like most people in Northern Australia, where the economy rides on the back of exported cattle, Everett worries about the future of the trade.

A New Zealand ban on live exports comes into effect this month, and the Albanese government’s pledge to end live sheep exports has sent a stir through the industry, which fears the same activism that ended that practice will eventually come for them.

Agriculture Minister Murray Watt has said the ban would not extend to cattle, but that has done little to quell concerns.

In a speech earlier this month, Northern Territory Cattlemen‘s Association president David Connolly said closing the live sheep trade would empower anti-livestock activists.

“If the minister’s boss says, ‘Go close the cattle trade’, what do you think will happen then?” Connolly said.

Cattle exporters have done much to improve conditions on the sea voyage and in Indonesian slaughterhouses since 2011.

Since 2018, Australia has exported an average of about 1 million cattle a year with an average mortality rate of less than 0.1 per cent.

“We saw in 2011 when it stopped just how much it hurt the economy up here,” Mr Everett said.

“It’s not just the stations, it’s the roadhouses where 20-odd trucks stop, and the hay providers and the businesses in the towns that support the stations.”

The Australian travelled to Carlton Hill as a guest of CPC.

Charlie Peel is The Australian’s rural reporter, covering agriculture, politics and issues affecting life outside of Australia’s capital cities. He began his career in rural Queensland before joining The Australian in 2017. Since then, Charlie has covered court, crime, state and federal politics and general news. He has reported on cyclones, floods, bushfires, droughts, corporate trials, election campaigns and major sporting events.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout