After two years of toil, the 400-page report recommended sweeping changes to the police force and the establishment of various oversight bodies, among other things.

Fitzgerald was attuned to a police culture that over decades had allowed corruption to flourish. “For a long time in the Queensland Police Force, speaking out achieved nothing but hardship, loneliness and fear,” he noted. “Those involved in misconduct were not punished. Those who reported it were.”

Last Thursday in the Queensland Coroner’s Court in Brisbane, as part of the new inquest into the Whiskey Au Go Go mass murder in 1973, Detective Sergeant Virginia Gray, who investigated the firebombing to assist the inquest, told the court that as recently as last year she had been ordered to redact several sections of her final report. The redacted sections dealt with the possible misconduct of several police officers who interrogated convicted Whiskey killers John Andrew Stuart and James Finch when they were arrested for the crime.

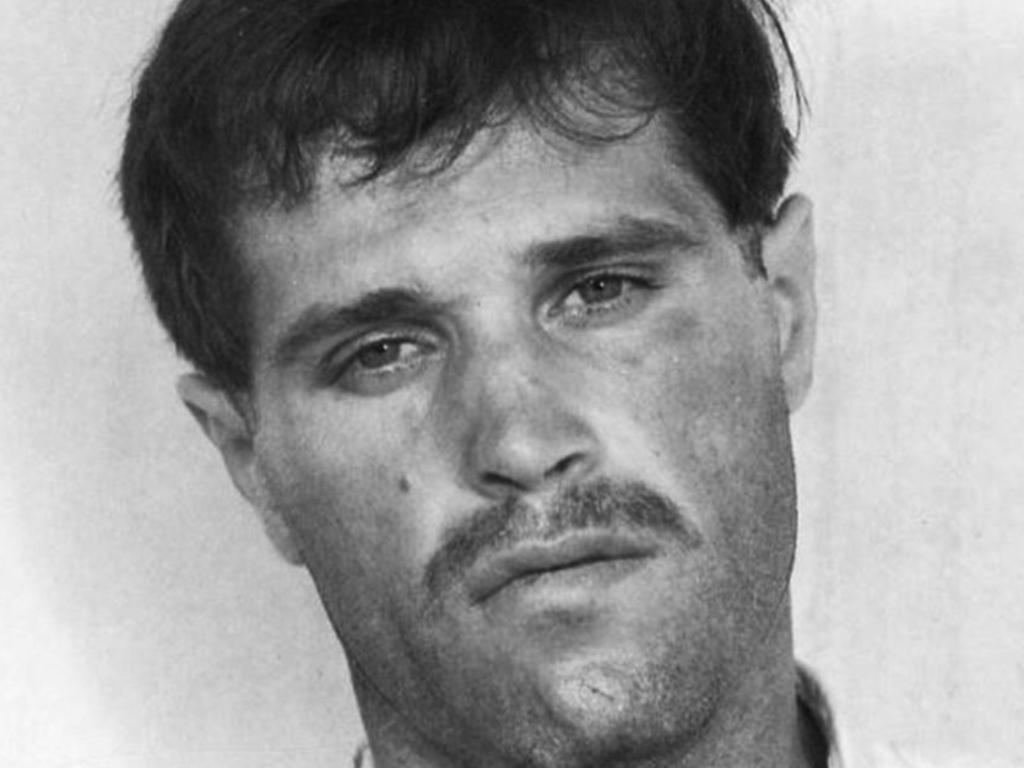

That alleged misconduct involved the “verballing” of both men and the bashing of Finch during questioning.

Gray told the court she was instructed by her boss, Detective Inspector Damien Hansen, to remove sections relating to the Finch unsigned confession and his interrogation by six detectives, including Ron Redmond, Syd Atkinson and former NSW detective Roger Rogerson.

Asked why she had to take out these “fairly standard” details from her report, she said Hansen told her to “leave that to the journalists and police haters”.

Queensland police counsel successfully sought a temporary non-publication order on Gray’s evidence to sort out the matter.

On Wednesday morning, that order was lifted.

In early reports, the issue was described as a “bombshell” and “astonishing”. Both are true. For those old enough to remember, it remains mind-numbing that, given everything Queensland went through during its painful Fitzgerald bypass surgery, allegations of attempts to rewrite or shape history through the selective release of information, or the removal of it, should rear up in a 21st century inquest as important as the Whiskey Au Go Go.

This issue prompted huge debate in the foyer outside Court 17 in the Brisbane Magistrates Court CBD complex where the renewed Whiskey inquest has unfolded for the past eight hearing days. How should it be interpreted? Was it an innocent administrative attempt by police to trim back and restructure Gray’s 80-plus-page report? Or was it a tendril stretching back to the pre-Fitzgerald era, aimed at protecting police reputations by withholding information?

On most days, at the inquest, it’s possible to see Gray bobbing in and out of interview rooms near the court or taking her place in the northeastern corner of Court 17.

With Detective Inspector Mick Dowie and their team, Gray helped close the 1974 cold case triple murder of Barbara McCulkin and her two daughters with the convictions of Vincent O’Dempsey and Garry “Shorty” Dubois in 2017. The resolution of that case sparked the fresh inquest, following suggestions Barbara was murdered for what she may have known about the Whiskey fire.

Gray is one of the finest Queensland police officers of her generation. She is tough, relentless and thorough. Last week, giving evidence about her report, she broke down in the witness stand.

It has taken 48 years and three months for the Whiskey atrocity to find its way back into court and the spotlight. This crime is a complicated tree with many branches. It traverses generations of police and their criminal counterparts.

One of the coroner’s tasks is to investigate the adequacy of the police investigation of the Whiskey firebombing, which left 15 innocent people dead. Gray’s job is to present her findings on that adequacy or otherwise. And the entire enterprise is to try to deliver a clearer picture of that horrible moment nearly half a century ago that took so many lives.

Were others, beyond Finch and Stuart, involved? And why did it happen?

Each day, Gray sits near the two rows in the public gallery reserved for the families and friends of the victims of the fire.

On Wednesday, one legal counsel told the court that the inquest was not a “Fitzgerald Inquiry Mark II”. Perhaps it’s not. But the stunning revelations by proxy allowed everyone to refocus on what the inquest is really about. It’s about the families of the victims. The ones who come to court, day after day, by public transport. The ones who sit quietly and patiently behind legions of suited counsel, hoping to pluck out of their legal arguments some sort of logical understanding of what happened to their lost mothers, fathers, brothers and sisters.

They sit and wait for the truth.

And they’ll be back in court on Thursday.

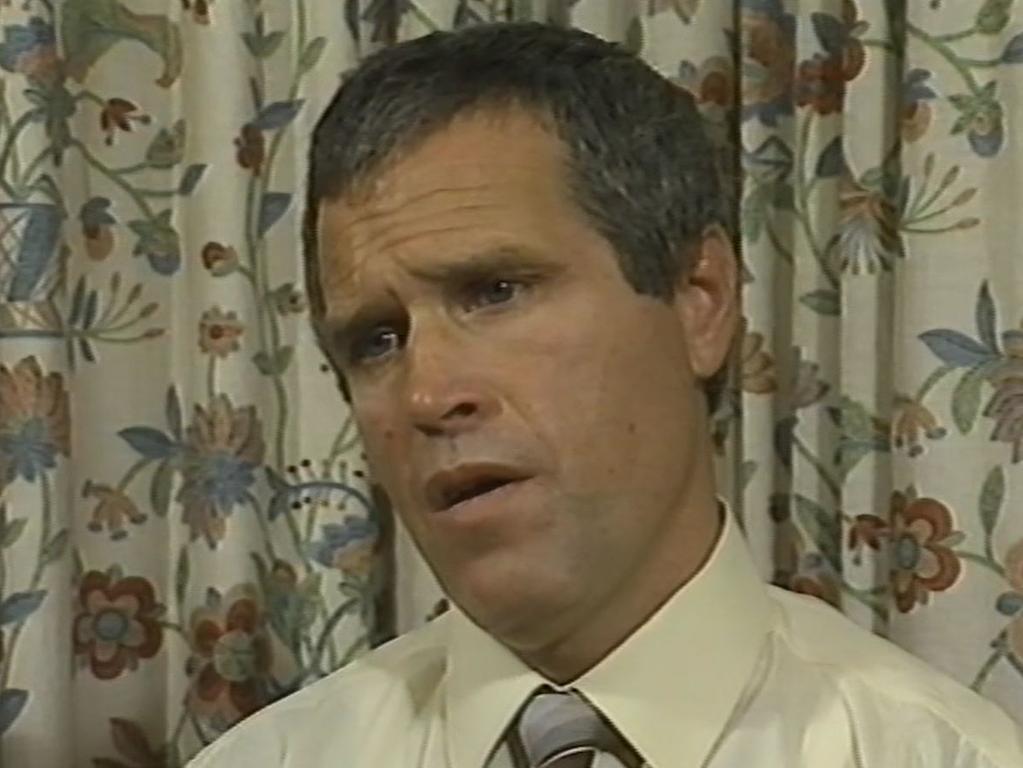

On a mild winter afternoon in Brisbane on July 3, 1989 – almost 33 years ago to the day – Gerald Edward “Tony” Fitzgerald, QC handed down the historic report of his inquiry into police and political corruption in Queensland.