Fear and loathing: our elders deserve so much better than this

Dad’s story isn’t pleasant or easy to share. It’s sickening. But it’s the reality of aged care in Australia.

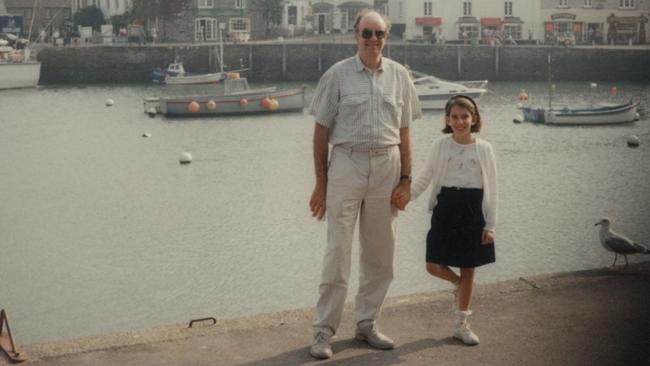

In my favourite photograph I have of my father and me, we’re on a family holiday in England. I’m nine years old and I’m standing in the middle of a fishing village in Cornwall perched on one leg, like a flamingo.

I had resolved that year to stand on one leg in photos because I thought it was a good look. It was not. But Dad is holding my hand and smiling.

He was bemused by my flamingo phase but he always stood beside me, even through my more ridiculous whims.

My father was also incredibly brilliant. His PhD theorised the movement of particles in fluid. When I open up my faded copy of his thesis, I am astonished by page after breathtaking page of complex equations and intricate, beautiful diagrams of genius I will never fully comprehend.

Dad’s intellectual curiosity was endless and infectious. His idea of a relaxing road trip was to try to teach me to solve algebraic equations from behind the wheel.

He taught himself computer programming. He wrote software. He took apart computers and put them back together again just for the hell of it.

He played the piano, and composed piano concertos in the evenings as a hobby. He read voraciously: he always had a volume of Churchill’s A History of the English-Speaking Peoples or a Wodehouse novel on the go. Above all, he taught me to love the life of the mind.

I have never known anybody who loved working as much as my Dad. His favourite saying was, “it’s only work if you don’t enjoy it”. His brain never stopped — until it did.

Dad was shattered when he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s at 64. As someone who’d always been highly intellectually active, he was devastated and frightened by his diagnosis.

Because he remained highly intellectually active, he managed to stay at home with my mother for longer than most: 14 years. During that time, he even taught himself to play the harmonica, and published some peer-reviewed research. But eventually his falls became too frequent, his needs too complex and in 2015, after a steep physical decline, my mother and I reluctantly moved him into care.

We chose the best place we could. It had lovely gardens. Spacious rooms with porches. A little cafe. It seemed civilised.

We had seen so much worse when viewing the alternatives: stark concrete buildings that looked more like minimum security prisons than nursing homes.

Dad found the transition into aged care very hard. He was one of the most high-functioning residents, and he was frustrated, depressed and bored.

Mum and I tried to find ways to brighten his days. We brought in huge stacks of books. We installed an electric keyboard for him to play. We visited daily. But the problems at Dad’s facility started almost immediately. He was frequently dishevelled. I would often find him with dried food caked on his face. He would be wearing stained clothes. It was unclear whether he had been showered.

He had grazes, cold sores, infections and other injuries that went untreated because nobody noticed them. Mum and I became de facto care managers. We had to exercise constant vigilance to ensure Dad got the care he needed.

Even worse, Dad’s vital Parkinson’s medication, Madopar, wasn’t being reliably dispensed on time. Madopar reduced Dad’s symptoms, including tremors, involuntary tics and lack of co-ordination, and increased his mobility. When it wasn’t administered at exact intervals, Dad would experience huge fluctuations in his co-ordination. As a result, he fell frequently. We raised this issue repeatedly. We got hollow apologies but nothing changed.

I was shocked at how few staff there seemed to be, too: a handful of carers for a whole wing. I would walk the length of Dad’s building to try to find somebody, and then discover that the carers had all taken their tea break together at the same time. I would hear motion sensors pinging, but no one coming to help.

Then Dad was mistakenly prescribed medication that completely negated the benefits of his Madopar. Nobody noticed. For more than five months, he was effectively without medication for his Parkinson’s. He had a serious fall and broke his hip. He was rushed to hospital. The doctors gave Dad a hip replacement but told us it was likely Dad would never walk again.

They were right.

Sadistic abuse

Now confined to a wheelchair, Dad returned to his facility. The pattern of neglect and unreliable care continued.

Then, one morning, Dad was wheeled to breakfast and the staff saw a huge, bright red, tennis ball-sized swelling in his elbow. He was rushed to hospital and diagnosed with a raging infection. The doctors were very concerned that it hadn’t been noticed and treated sooner. Mum and I began to ask questions about how the infection had been missed.

A whistleblower came forward and told us that the woman responsible for Dad’s showering had been deliberately and sadistically abusing him. She had seen the carer leaving Dad in distress in soiled incontinence pads on purpose. Moving his wheelchair away from the bed so that he was immobile. Closing his door and telling the other staff he was sleeping, when in fact he was awake and desperate for a shower. Leaving fresh incontinence pads out of reach and telling him to get them himself, knowing full well he could not. Taunting him verbally and telling him she was “sick of his shit”. Victimising a man whose quality of life was so diminished already.

The whistleblower told us she had come to Mum and I because if she’d gone to the facility’s management, nothing would be done. I was enraged and sickened. I was also haunted by the thought of what else the abuser might have done to Dad. She worked the night shift and was frequently rostered alone with him for long periods.

I’ll never know what else may have happened to Dad. I expected the facility to fire Dad’s abuser immediately. What happened next shocked me to my core.

Stonewalling

Mum and I attended a meeting with the management. The meeting was on St Patrick’s Day. I remember this vividly because when the facility manager walked into the meeting room to discuss Dad’s abuse, he was wearing a huge, lurid green mardi gras-style shamrock necklace. He hadn’t even seen fit to attend the meeting in attire that reflected the gravity of the situation. It was utterly surreal. As I was trying to express my rage and sorrow at what Dad had endured, my eyes kept snagging on the necklace. It said it all.

The facility manager wasn’t upset about what had happened to Dad. He was upset the whistleblower had come to us and not to him. He kept asking us who the whistleblower was.

The manager offered to move Dad’s abuser to another wing of the facility, away from Dad. But I couldn’t sleep, knowing she would likely be victimising other vulnerable residents. The facility stonewalled me. It was interested only in identifying the whistleblower.

I was distraught. I went to the police. I went to Elder Abuse. I went to the regulator, the Aged Care Complaints Commission (ACCC), and made a formal complaint.

I was shocked that none of them — not even the ACCC — had the power to pursue the abusive carer. It was a lonely and exhausting time. Nobody seemed interested in the most worrisome aspect of the story: that Dad’s abuser was still in the system, entrusted with caring for some of the most vulnerable people in our community.

I was stunned by the lack of rigour and transparency in the way the ACCC handled my complaint. Everything was conducted over the phone. The complaints officer assigned to my case relayed the facility’s response, which sounded like a bunch of corporate jargon to me: it said it would undertake “toolbox sessions” and retraining. Nothing substantive. When I pushed back and said that I was alarmed at the idea Dad’s abuser might be victimising others, the complaints officer said the ACCC didn’t have the powers to do more.

I got the impression the ACCC was more interested in closing Dad’s case than in holding the facility accountable.

I later learnt that the regulator had earmarked Dad’s case as “suitable for early resolution’”— despite the fact they had rated it as of “major” concern, due to the imminent risk to Dad and others. The explanation the ACCC gave for this inexplicable decision was that there was no related history of complaints at Dad’s facility. This infuriated me. I got the impression that the regulator waits for the complaints to pile up before taking serious action.

After weeks of lost sleep and a constant roiling in my stomach, I begged the whistleblower to go on record, which she did, under great fear of retaliation.

Finally, the abuser was sacked from Dad’s facility.

After my ACCC complaint was closed, I learnt that a full week after the whistleblower had come forward and the facility had sacked the carer, it misled the regulator by saying “no staff could substantiate” claims of abuse. If the regulator had made even a cursory investigation, it would have known that wasn’t true.

Anything goes

I wish Dad’s story ended there. It doesn’t.

Instead, in the two years since, Dad has suffered six broken ribs from falls, including two left undiagnosed and untreated. Once, I even found an unaccompanied corpse covered by a blanket on a gurney just lying in the hallway.

There have been countless instances of neglect, minor and major. Injuries and infections not properly treated. Meals Dad has had to choke down without chewing because staff have forgotten to put his dentures in. Hygiene issues. UTIs from being left too long in wet incontinence pads.

Dad’s still living in the same facility to this day. He’s far too frail now to be moved. My mother and I still can’t relax about his care, because the same issues of subpar clinical observation and low staff numbers are ongoing.

None of this is pleasant or easy to share. It’s sickening. It’s been heartbreaking for my family to live through, but it’s the reality of aged care in Australia today: toothless regulators, no minimum staffing requirements and inadequate protections for our most vulnerable enshrined into law.

It’s the wild west of healthcare: anything goes.

Preparing to testify about what my Dad has endured was harrowing. I felt tired in my bones. But walking into court, I was thinking of him — and I was aware the weight of responsibility he once shouldered has now passed to me.

Our elders deserve so much better. They are our grandparents and parents, our neighbours, colleagues and friends. We owe it to them to demand a kinder, more compassionate sector that is robustly regulated and adequately staffed. We owe them real accountability and oversight. We owe them dignity.

My father always used to say he would rather die than go into a nursing home. I hear that sentiment often. But the reality is as our life expectancy increases, more of us will need care in our final years.

We owe it to all those in the system today — and all those yet to enter it — to fix it for good.

Sarah Holland-Batt is an associate professor at the Queensland University of Technology. This formed part of evidence she gave at the aged-care royal commission this week.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout