Family’s lives lived well, but life expectancy just got a little shorter

New forecasts on life expectancy cast doubt on whether we’ll continue to live longer lives.

Melbourne retirees Joe and Talya Pasmanik did what we all should do: they gave up the cigarettes years ago and judiciously watch what they eat and drink.

Aged 72 and 68 respectively, the couple plan to be around to see a fourth generation of their family grow up.

But new forecasts on life expectancy cast doubt on whether Australians will continue to live longer and healthier lives.

By the time their two grandkids and grand-niece, Tara, 2, are old enough to have children of their own, life expectancy will be in decline, reversing decades of advances that pushed average longevity past 80 in this country.

A baby boy today can expect to live for 80.5 years and a girl 84.6 years, putting Australia in the top tier of world life expectancy.

However, rising obesity and high rates of road accident death and suicide among young people are predicted to overwhelm future gains in medical science that should allow Australians to live even longer.

This has compelled the Australian Bureau of Statistics to wind back long-term life expectancy projections, the first time the index has dipped.

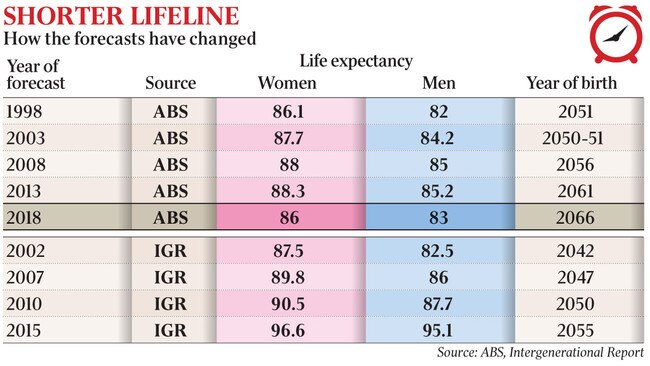

Under the 2013 outlook, boys born in 2061 could expect to live, on average, to 85.2 years and girls to 88.3 years. But late last year the ABS quietly revised down its forecasts to 83 for boys born in 2066 and to 86 for girls — an unprecedented turnaround in life expectancy that would have an impact not only on population projections but planning for health, aged care and retirement.

For the Pasmaniks, this was sobering news, puncturing their expectation that medical advances and increased lifestyle awareness would inevitably boost the prospects of future generations. The big, exuberant family from Elsternwick in Melbourne’s leafy east is a case study in how Australians are getting more out of life.

Egypt-born matriarch Heddy is still going strong at 92, independent and active, cooking her own meals in the home where the four generations gathered yesterday.

Her daughter, Talya, a retired social worker, eats vegetarian and addresses her mum’s four-cheese macaroni gingerly. “It’s lethal,” she joked.

Talya and husband Joe, a former finance manager, have three daughters, Michelle, 40, Davina, 38, and Nicole, 34, and two granddaughters, Mali, 7, and Poppy 4. Toddler Tara, recently turned two, rounds out the generation that will have to come to grips with the reversal in life expectancy.

Mr Pasmanik is not convinced it will happen. “People are living longer than they used to and one of the major factors is that medicos are keeping them alive … that’s not going to stop,” he said.

And, as his wife points out, you live and you learn. In their younger days they smoked, had a drink too many on occasion and paid less attention to diet than their daughters now do.

“I’m an optimist about people being educated … I think there will be a groundswell of active parents who are more sophisticated about advocating for what they choose to eat,” Ms Pasmanik said.

University of Melbourne laureate professor Alan Lopez, an authority on the global burden of disease, has warned that Australia will start to fall down the life expectancy rankings if more people don’t heed warnings about lifestyle abuses.

He said the long-running gains in life expectancy began in the 1970s and accelerated in the 80s and 1990s, fuelled by public health measures such as anti-smoking campaigns, good diet promotion and efforts to reduce the road toll. These, plus advances in medicine, brought a dramatic reduction in premature deaths, particularly due to cardiovascular disease.

“In about 2010, however, that long-term decline in cardiovascular mortality stopped in Australia,” Professor Lopez said. In places such as the US, Britain and Canada, cardiovascular mortality rates had started to rise again.

Professor Lopez suggested that rising rates of obesity were a major contributor, along with stubborn rates of smoking. Separately, there has been a concerning rise in youth suicide in recent years and difficulty reducing the road toll.

“We don’t really understand why, but if we don’t do something about that then the prospects for significant increases in life expectancy in Australia in the next 20 years are very slim,” he said.

Documents obtained by The Australian under Freedom of Information laws show that at a Population Roundtable in January, Treasury officials acknowledged that the 2015 Intergenerational Report that guides government spending on social services “assumes greater improvements in mortality than recent ABS projections”.

That report was released by then treasurer Joe Hockey as he proposed an increase in the retirement age, since abandoned by the Morrison government. At the time, it was predicted that boys born in 2055 would live to 95.1 years and girls to 96.6 years — not only far longer than the ABS has forecast but roughly six years more than Labor’s Wayne Swan as treasurer in 2010 had predicted for those born in 2050.

Actuary Richard Boyfield, the retirement solutions leader for Mercer, said the change in life expectancy for younger, and possibly future, generations warranted further analysis and should focus on the significant variation within the community.

“A lot of the work that has been done on mortality around the world has highlighted that those with healthier lifestyles and better access to healthcare — generally speaking, those who are more affluent — tend to live healthier and longer,” Mr Boyfield said.

He said the average lifespan would affect the provision of social security, aged care and the pension, alter healthcare demands and have a knock-on effect for population demographics.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout