False tale of university rape exposes the dark side of the #MeToo legacy

An awkward sexual encounter, some doctored text messages and a practiced liar was all it took to put Jacob frighteningly close to prison. Proving the truth took bravery — and extraordinary legal skill.

Tom Molomby rises slowly to his feet. Twelve pairs of hostile eyes follow him.

The prosecution has just laid out its case against the 22-year-old defendant sitting in the dock.

It’s an ugly picture that has clearly left a mark on the newly empanelled jury.

The prosecutor has not spared them explicit details. How the young man lured the victim to his college room, tore off her shorts and underwear, repeatedly raped her as she begged him to stop, slapped her across the face and then contemptuously kicked her out of his room.

Now Molomby is opening for the defence. He turns to meet the cool gaze from the jury box.

“Members of the jury, what you have heard outlined by the crown prosecutor isn’t a very pretty story,” he begins. “But not for the reasons he’s outlined.”

The veteran barrister was once a television and radio journalist: he knows how to hook an audience.

“The defence case is that this young woman’s story is a complete concoction, a malicious series of false allegations,” Molomby tells them bluntly.

“This is not a case of mistake or misunderstanding; this is a deliberately false story.”

That’s not what they were expecting. Molomby lets the thought settle in.

Over the next few minutes he tells the jury about “the general landscape” of the case, but also makes it clear he’s not going to spell out the details. The truth is a jewel inside a parcel and they’re going to unwrap it together over the next two weeks of the trial: just pay attention.

Molomby needs them to come along with him on this journey, because if they don’t, Jacob, the young man in the dock, is heading for anything up to 10 years jail. The veteran lawyer has chosen a perilous course.

The easy route, the one he refuses to take, would be to suggest there was some kind of misunderstanding involved: mixed signals, wrong cues. That the woman we will call Sarah at least believed what she was saying.

No. She is a liar, Molomby says. Apart from the fact that there was sex, everything in her account of what happened in the room is a complete fabrication.

The words he will later use to describe Sarah, in a long, surgical dissection of the case, are: Ruthless. Remorseless. Shameless. Calculating. Cruel.

“It’s impossible to think of any reason why she could rationally have wanted to destroy Jacob’s life by sending him to prison for many years,” Molomby tells The Weekend Australian.

He believes there are more such people in the world than we would like to think.

“One wonders how such people come to be. The enormity of what they are trying to do to someone else does not deflect them.”

He knows it’s not a popular view. A global moral movement has been constructed on the premise that a woman must be believed when she says she has been sexually assaulted. Why would any woman claim to have been raped when she was not?

And what decent, self-respecting juror would doubt her?

Sarah’s account

Jacob was not expecting to hear from Sarah that night. They had met two months before, in February 2019, at the university in which they were both newly enrolled. He was 18; she 19. They immediately hit it off. They would often sleep together in the same bed but didn’t have sex. She said she had adopted Muslim beliefs and didn’t want sex before marriage.

But she drank and smoked and was excited about the relationship. There was much sexual innuendo between them.

“Do you want to lick my pussy by any chance?” she asks Jacob in one message. “I’m just out of the shower so I’m kind of naked,” she tells him in another.

It was a tumultuous relationship. Text messages show Jacob broke it off, or tried to, several times. On one occasion, she would later say, he had tried to have sex with her after the pair had a drunken night out and she rebuffed him. They had argued and he had left her room angrily, slamming the door behind him.

The relationship stalled.

On April 8, 2019, Jacob was in his room at the college with a mate and at about 10pm posted a Snapchat to his group of friends captioned: “Telling me bedtime stories.”

To his surprise, Sarah messaged back: “Can I come and tell you bedtime stories?”

Yes, he told her, but he was going to bed early. She arrived at his room about three hours later, at 1.15am. His friend had long gone.

What follows is her account of the visit.

Sarah says she was surprised to find him alone as she “had expected that there was some sort of social gathering in the room”.

She sat on the bed and they chatted. It was his birthday that day.

“Are you going to give me a birthday present?” he asked. Sex was the least she could give him, he suggested.

Sarah reminded him of her views on sex before marriage.

“Why do you look like a porn star but act like a virgin?” Jacob asked.

When she lay back down on the bed, Jacob lay down beside her and held her breasts with his hand, then took hold of her wrists and pinned them behind her head.

“I’m not an object,” she told him.

“You are an object, you’ve been teasing me for far too long,” he replied.

He pulled off her shorts and underwear, and tossed them across the room.

Sarah tried to get out her mobile phone but Jacob took it and threw that across the room too.

Then he pulled his own pants down and tried to push his penis into her.

As she struggled against him, he grabbed her by the hair and pushed his erect penis into her mouth, hitting the back of her throat. She pulled away.

“Please stop,” she begged.

Instead, Jacob pushed her back onto the mattress and penetrated her.

“Just let it happen,” he told her. When she continued to struggle, he slapped her across the face.

She jumped off the bed but he grabbed her and pushed her back down, pinning her on the mattress and penetrating her again.

She began to cry.

At this point Jacob, who had basketball practice at 6am, said she was “too much effort” and told her to get out.

She dressed, picked up her phone and fled, still crying.

It was a story she would go on to repeat, in varying form, to other friends, to a doctor, to the college master, to the police, and – ultimately – to a jury.

Slow fallout

At 3.30am, Sarah arrived at the room of a close female friend in the college, sobbing uncontrollably.

Jacob had raped her, she said.

Later that morning, Sarah went to the university counselling service, then to the hospital, which she left after being told she might have to wait for nine hours because of the number of people ahead of her in the queue.

That afternoon she spoke to the Master of the college. She told the Master she had received a text message from Jacob asking him to come to his room to tell him a bedtime story, but instead had been raped.

The college head decided she was telling the truth and told her: “I believe you”.

At the trial, the Master explained that under the college’s “trauma-informed approach … it is important to listen to a victim that comes to you and support that person and to believe them if what they are presenting is real.”

Back at the college, Sarah told a friend how the doctor who examined her at the hospital discovered the assault had been so violent it had split the skin of her vagina and had to be glued together.

She showed friends a text message Jacob had sent after she left, saying: “I don’t think it helped that I had to force you into sex.”

That single incriminating message seemed to end all doubt about what had occurred.

Sarah withdrew to her room, seemingly inconsolable.

The fallout reached Jacob slowly. Friends blanked him; moved to other tables in the dining hall when he sat down.

Rumours cascaded through the college: Jacob had done some “weird sexual rapey shit”.

He sought out a mutual female friend, desperate to work out exactly what Sarah was claiming had happened. The “friend” secretly recorded the conversation in a bid to get a confession that would help Sarah’s case.

But Jacob’s account of what had occurred was startlingly different to Sarah’s.

They had awkward, but consensual sex, Jacob said.

“She literally outright said to me, the intention of her coming to my room was so that she could have sex with me,” he told the woman, not realising she was taping the conversation.

“And, like, this is really awkward, but, like, because of everything that had happened, I just, like, I couldn’t ejaculate. I said to her multiple times, do you want me to stop? And then she’ll say no. Or she’ll say yes, and then I’ll stop and she’ll be like, why did you stop?”

“And then she just said, like, ‘What the f..k are you doing? What’s wrong with you, don’t you like me? Do you hate me?’ … she was just, she was really, really, really angry. She started yelling at me … Like, ‘do you not feel attracted to me?’”

They tried again, he says, but he still couldn’t climax. He also claimed this was the second time they’d had sex, and that Sarah had found it painful on both occasions.

It’s clear from the tape his interrogator doesn’t believe his account. Everyone knew Sarah’s beliefs about pre-marital sex.

The doctor who examined her handed a sexual assault investigation kit to police.

The wheels were now in motion. Jacob had still not been told anything of what was occurring.

A week after the incident, the Master summoned Jacob “for a chat” – then asked him to recount in detail, over a two-hour meeting, what had occurred, but refused to give him any information about the complaint beyond that it involved “sexual misconduct”.

“Basically, the Master asked me to come to a meeting already disbelieving anything I was going to say,” says Jacob.

A week later, he was expelled from college. Two months later, he was charged with sexual assault.

The case against the young student was compelling. There was CCTV footage of Sarah in the college corridor as she made her way to and from his room.

She had reported the incident to various people almost immediately, including the injuries she sustained. And there was that text, sent by Jacob himself – he had “forced her”.

Old-school lawyer

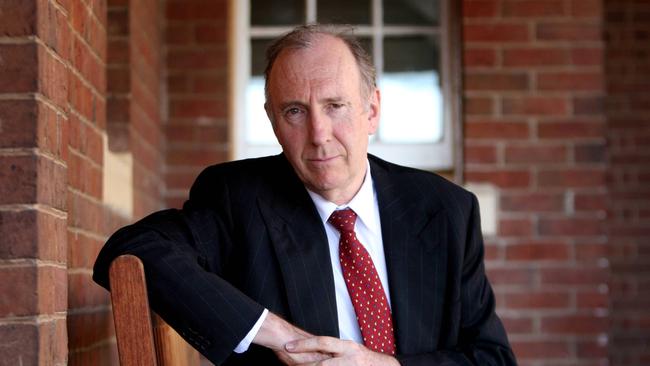

If you were ever falsely accused of a crime, Tom Molomby SC is the kind of lawyer you’d want in your corner – though not necessarily the most obvious pick in a case that involved unscrambling hundreds of text, Facebook and WhatsApp messages.

Molomby is old school. He’s never owned a mobile phone. In a recent defamation case, he joked with a judge that when it came to Facebook “I would describe myself as someone in the sandpit with the alphabet building blocks”.

A barrister for more than 30 years, Molomby began his career as a journalist with the ABC’s This Day Tonight program. His speciality – or inclination – is seemingly unwinnable criminal and defamation cases.

He has written four books on wrongful convictions, including a definitive account of the framing of Ananda Marga members for conspiracy to murder, following the 1978 Hilton Hotel bombing. One of the first defamation cases he defended was a lawsuit against himself by Richard Seary, the suspect informer in the Hilton bombing case. Molomby won.

More recently, when a blogger named Esther Rockett was sued by Universal Medicine cult leader Serge Benhayon, Molomby took on her defence and won, leaving Benhayon – who proclaimed himself the reincarnation of Leonardo da Vinci – forever branded “a charlatan who makes fraudulent medical claims”.

When Jacob’s case arrived at his door, Molomby didn’t hesitate.

Jacob says Molomby reminded him of Gandalf from Lord of the Rings: “very wise and intelligent, and with an almost whimsical air about him at times”.

“Having Tom on board ticked every box you’d want. It really felt like no one else in the world could have done the job like he did it.”

Frozen in time

Jacob’s trial, delayed several times by Covid, began on May 2, 2022, more than three years after the alleged attack. He had watched his friends move on with their lives. His was frozen in time.

“For me the idea of going anywhere near the city – and the university – gave me a sick feeling in my stomach and I was so scared of something happening that I just stayed home,” he says.

“I said to my parents during the case that I couldn’t remember what it felt like to live without it over my head.”

Sarah took the stand at the start of the case. The young woman answered every question the prosecutor asked, quietly but confidently. She recounted her story of the rape in grim detail.

Then Molomby began his cross-examination. She was an impressive witness, he says, by turns calm, distraught, assertive, tearful.

“She wept at times uncontrollably, asked for an adjournment because she felt faint, reacted to adverse questions with scorn, disbelief and indignation,” he says.

But gradually her story began to falter. Jacob and Sarah had had sex before. She had told friends about it. She described it to one as “awkward but not necessarily unenjoyable”. She even told the Master to whom she reported the rape allegation: “This wasn’t the first time I had sex with (Jacob). We had sex once before in my room. It was consensual, it hurt and I didn’t like it.”

Later she sent the Master another message: “Me and (Jacob) had hooked up once in the past leading up to this, and that’s the only time which was also a very uncomfortable scenario in itself.”

But in court she was adamant the pair had never had sex. She denied having told the Master they had. There was just some consensual “grinding”, followed by an unsuccessful attempt by Jacob to penetrate her, she said.

“Hooked up” simply meant kissing, she said, even though she’d previously acknowledged kissing him on dozens of occasions, even sending him pictures of hickies on her neck.

Facebook messages

Other claims fell apart. The remarkably clear CCTV footage of the corridor recorded Sarah as she left Jacob’s room but showed no sign of any tears or distress.

As Sarah’s friends filed in to court to give evidence it became clear that her story had evolved in the telling.

She told one friend that Jacob had strangled her, but that claim never appeared in the account Sarah gave to police or in court.

The skin of her vagina had not been split or glued. The doctor who examined her – a specialist in sexual assault cases – gave evidence and provided detailed clinical notes stating minor abrasions present could easily have been the result of consensual sex.

Sarah hadn’t even seen the doctor when she told her friend about how the horrific injury had been treated.

“One of the alarming things is how easily this woman took the whole system for a ride – the police, the prosecution – and I don’t blame them.”

- Defence barrister Tom Molomby

“Her enthusiasm for the story got the better of her,” Molomby says. “She spun it too early, before an essential element had actually happened.”

Sarah went overseas to visit her family for almost two months after first making her allegations.

When she returned, she gave police a statement and handed them her phone. All her text messages from before her trip had been deleted. Some Facebook messages appeared to be intact.

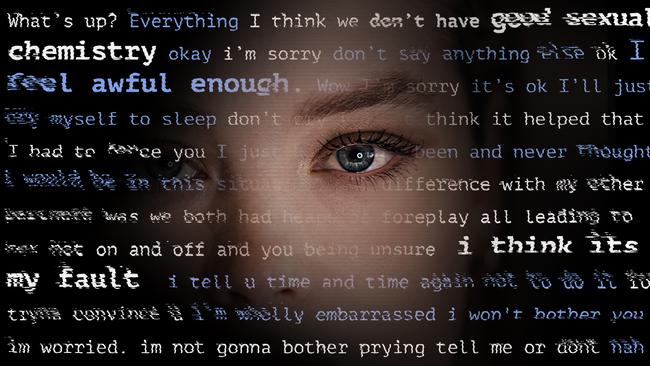

On the night of the alleged rape, Sarah messages Jacob at 1.54am, just seven minutes after she leaves his room.

“Jacob”, she flags.

“What’s up?” he replies.

Sarah: everything.

Jacob: I think we don’t have good sexual chemistry

Sarah: okay

Jacob: i’m sorry. my dick legit hurts and I can’t even get it hard now even when im truna jack off

Sarah: don’t say anything else

Jacob: ok

Sarah: I feel awful enough. Wow

Jacob: I’m sorry

Sarah: it’s ok I’ll just cry myself to sleep

Jacob: don’t cry

Sarah: I actually don’t know what to do lmao. i’ve never felt this shit, like ever, idk why I’m telling you this

Jacob: is there anything I can do

As Molomby says, questions swarm around this conversation, which would continue intermittently for more than an hour into the early morning.

“There is no obvious reason why a woman would contact the person who had just raped her, except perhaps to lodge a protest from a safe distance,” he says.

Molomby cross-examined Sarah about the exchange.

Q. You say that you just left a man who had raped you and who was angry. What are you hoping to get out of him by messaging him?

A. I was extremely stressed at the time and I didn’t know what to do. I was hoping there was some sort of justification for his actions.

Q: So you see him saying, ‘I don’t think we have a good sexual chemistry’ … wasn’t the answer to that: ‘How could we; you just raped me?’

A: No, like I said, you can’t determine how someone will feel. I was trying to justify what had happened.

The online conversation between Jacob and Sarah continued.

Jacob: I don’t think it helped that I had to force you into sex or at least the whole situation didn’t feel relaxed.

Sarah: I just have never been and never thought i would be in this situation.

Jacob: The difference with my other partners was we both had heaps of foreplay all leading to sex not on and off and you being unsure

Sarah: yeh but (name)

Jacob: i think its my fault

Sarah: i tell u time and time again not to do it

Jacob: for tryna convince u

Sarah: i’m wholly embarrassed i won’t bother you again. Dw (don’t worry)

Jacob: im worried. im not gonna bother prying tell me or dont

Sarah: nah i just i’m sorry that’s all

Jacob: im sorry too. I just hope ur alright. all is good on my end

Sarah: I am a literal mess. I beg u

Jacob: I have to get to sleep. we can talk tmoz

The messages end with:

Jacob: do u need anything

Sarah: nah dw

When the defence team starts going through the messages in Jacob’s Facebook, they realise the conversation is very different to the one from Sarah’s phone. The conversation doesn’t end – as it does in the version police downloaded from Sarah’s phone - with Sarah saying “nah dw”. It ends with Sarah telling Jacob: “have a good night romp tomorrow.”

At the trial, Molomby asks Sarah how those good wishes for his birthday celebrations came to be deleted from her phone:

A: I don’t know why that is there or not there. I still haven’t claimed this as my own conversation.

Q: You deleted this because you believed it didn’t fit your story of what happened that night.

A: You’re wrong. I do not admit to deleting that message and I will not admit to that because I didn’t do it or I don’t remember.

Q: You didn’t do it or you don’t remember?

A: Exactly.

As the defence team further compare the messages left on Sarah’s phone with those on Jacob’s, they realise whole slabs have been deleted, or in some cases, just a few crucial words.

Sarah messages Jacob again at 2.44am:

Sarah: i don’t know how to say this or whether i should say it at all but i just want you to know something, it’s not our sexual chemistry and it’s not about my religion, it’s about something that happened when I was 13 and nothing has been the same since, please understand that … i’m sorry”

Jacob: im sorry that happened

Sarah: nah i don’t need you to feel bad that’s not what i’m trying to do

None of those words appear in the messages that police downloaded from Sarah’s phone and which the DPP was using to prosecute Jacob.

But Molomby is in a bind. He can’t cross-examine Sarah about what happened when she was 13 because of the rules excluding evidence of past sexual experience.

The barrister can only ask if she remembers such a conversation.

Sarah says she can’t recall.

Q: Do you deny that you sent such a message?

A: No, I don’t recall. How can I confirm or deny something I don’t recall? How many times do I have to tell you?

Q: I’m suggesting to you that there was a message in those terms that you deleted from Facebook before you gave your phone to police.

A: And I disagree with you.

Q: Those messages were removed by you from your Facebook, weren’t they?

A: I don’t confirm or deny that.

Then the defence team stumble upon a completely separate conversation Sarah has been having that night.

While she’d been messaging Jacob online, Sarah had been messaging her mother, who was overseas, telling her what she says has just happened with Jacob.

Sarah refers to the traumatic event from her childhood: “It’s been this way ever since O---- ruined my life.”

Her mother writes back, suggesting Sarah has two options with Jacob: “(1) be honest. Say you had a panic attack due to something that happened with an ex boyfriend a long time ago (2) lie. Say you felt guilty about …”

The rest of the sentence is cut off. The partial exchange is only preserved because Sarah sent Jacob a screenshot of it during the volley of messages that night.

Sarah tells Jacob: “I always go with option two and I think it’s time to tell the truth for once.”

Jacob replies: “I’m glad you were honest. I just hope you’re alright.”

That exchange had also been deleted from Sarah’s phone.

The surgical excisions have changed the tenor and substance of the whole conversation.

The brutal man who has allegedly just raped Sarah and kicked her out of his room so he can get some sleep before basketball is still talking to her at three in the morning.

Sarah’s statement that she is “a literal mess, I beg you” wasn’t about the alleged rape but about a traumatic incident from her past.

Jacob’s apparently indifferent “I have to get to sleep” in response actually comes later, after she has begged him not to tell anyone, and he has responded: “I won’t.”

The messages fit with Jacob’s scenario of a sexual interaction that has gone wrong for reasons he’s puzzled by, but she isn’t.

The fragmentary phone records retrieved revealed something else. In the days after the alleged rape. Sarah had certainly been holed up in her room – pursuing exchanges on Tinder.

Grave risks

Jacob took the stand on day nine of the trial.

There are grave risks for any defendant, even an innocent one, in giving up the right to silence in a criminal trial. It meant the prosecution would be able to cross-examine him. But after years of enforced silence, Jacob was determined to have his say.

“I spent most nights for the three years leading up to my trial thinking about what I would say, imagining fantastical scenarios where I would stand up and proclaim my innocence,” he tells The Weekend Australian.

“And yet the trial is a very sterile and almost scripted affair where it is very much against your best interests to say anything extra than you need to say. I knew I had to keep my composure.”

Jacob’s account of the night mirrored what he’d said to Sarah’s friend, when he was unaware he was being recorded.

Sarah had come to his room and suggested they have sex. They had consensual sex, but he wasn’t able to ejaculate. She got angry. It was awkward. They tried again. It didn’t work. She left.

In two days of cross-examination by the prosecutor, Jacob’s story remained consistent.

In his closing address to the jury, Molomby begins with a story about moonboots.

Sarah had a part time job at a dental surgery but after a particularly heavy night of drinking, didn’t want to go to work. She texted her boss saying she’d broken her leg. But the next week she had a problem with how to explain the broken bone. So she advertised for a moonboot on Gumtree and wore it to work. She boasted about it, posting a photo of her foot in the boot captioned: “Ready for work tomorrow!”

In court, she claimed to have no memory of the incident.

The point Molomby wanted to make was not simply that Sarah was a liar, but that she was an extraordinarily good liar.

“You cannot tell by the way she gives her evidence whether it’s true or whether it’s lies, because she does it all the same,” Molomby told the jury.

“She can tell a blatant, flat-out, clear and important lie, that’s on this one, vehemently, assertively, confidently, just the same way she does everything else, and that means you cannot tell rationally whether it’s true or whether it’s false.

“This woman is a creative, self-serving, self-glamorising and dramatising liar,” he said.

The trial ran for 14 days. The jury were out for two hours.

When they filed back into court to deliver their verdict, Jacob knew the result before they took their seats.

“One of the men had his eyes locked onto mine and I sort of just raised my left eyebrow as if to say ‘well?’ and he gave a careful, slow and reassuring tilt of his head forwards which only meant one thing. I just looked up to the ceiling and at that point I knew it was all over.”

Moments later, the foreman confirmed it, announcing emphatically “NOT guilty” to all four counts.

The judge awarded Jacob a rare “certificate of costs”, meaning the prosecution would have to pay for some of the defence’s costs.

Such a certificate is only granted when a judge finds that if what was known at the end of the trial had been known from the start, it would not have been reasonable to prosecute.

Was the verdict a vindication of the system? Molomby’s not sure.

“If the young woman ever decides to try the same stunt against someone else, the defence will not be able to use her behaviour in the young man’s case against her,” he says. “Furthermore, because the protection of her identity continues after the case is over, despite having made a false complaint, the next person wouldn’t have any way of knowing her history.”

Nor would the next accused person necessarily have someone as tenacious as Tom Molomby in their corner; although he’s too modest to point that out.

Molomby makes no criticism of the trial prosecutor, who pursued what looked like at the start like an eminently winnable case.

“One of the alarming things is how easily this woman took the whole system for a ride – the police, the prosecution – and I don’t blame them. If I’d been the prosecutor, I would have prosecuted this case.”

But the veteran barrister is alarmed that such a case got as far as it did. He’s written a minutely detailed study of the whole case titled: #MeToo Could Be You, Too.

Jacob has lost three years of his life but knows it could have been much worse.

He now lives with his brother and two of his brother’s friends in a share house with two cats.

“I try to find happiness in the little moments in my life. It sounds juvenile but I like to sit outside and watch the cats in the garden sniffing at new plants, chasing birds and tentatively taking new steps into unexplored regions,” he says.

“It allows me to appreciate the world in a simpler light. I realised just now that perhaps the sense of innocence and curiosity I see in them is something that was stolen from me, and I crave that now.”

He says things are getting better in his life, but relationships with women are difficult. When’s a good time to tell your date you were charged with rape?

And there are trust issues. “It’s almost like you’re assuming something bad is going to happen before it happens – and that sort of defeats the purpose,” he says.

He believes that the #MeToo movement could be a powerful force for good, despite the damage it did him.

“The essence of the #MeToo movement is that when someone comes forward with a story, if you don’t believe them straight away, you’re seen as just a horrible person,” he says. “So everyone kind of had no choice but to believe what Sarah was saying.

“But I think the #MeToo movement still is important for actual victims of sexual assault, and I wouldn’t want anyone who experienced that to be scared about coming forward,” Jacob says.

The big question still haunts Jacob: why did she do it?

“I think she kept peddling the lie for the sympathy and attention and had a narcissistic, perhaps even psychotic disposition that caused her to essentially dig herself a hole,” Jacob says.

“I’m sure she reached a point where she was thinking she should come clean but at that point, how do you tell your friends and family and the police that you have been lying for months about such a horrendous thing.”

Molomby is less forgiving.

“There are ruthless, awful people who will make false complaints, just as there are ruthless, awful people who commit other crimes,” he says.

“And they will do it with a heartlessness and a remorselessness and an effrontery that most people find it really difficult to accept, because we all tend to judge by our own standards.

“That’s a logical mistake. Because if the person is making a false complaint, they’re not the sort of person you are.”