Economy ‘largely stalls’ as mortgage bill doubles

Australia’s mortgage interest bill doubled to $83bn in the past financial year, as soaring rates and cost of living crushed consumer spending and depressed the economy in the three months to June.

Australia’s mortgage interest bill doubled to $83bn in the past financial year, as soaring rates and cost of living crushed consumer spending and depressed the economy in the three months to June.

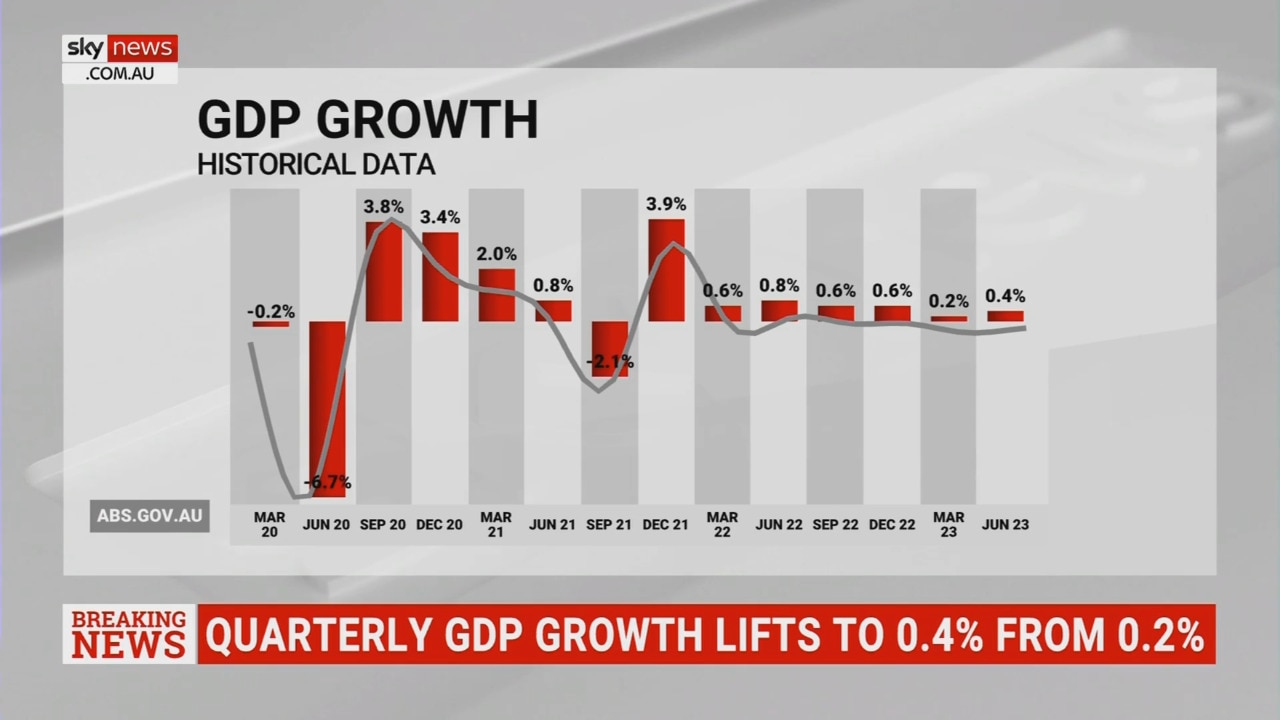

National accounts figures released on Wednesday revealed the economy continued to slow into the middle of the year, as annual growth in real gross domestic product decelerated to 2.1 per cent from 2.4 per cent in March.

The most aggressive rate hike cycle since the 1980s and high inflation flattened growth in consumption in the latest quarter, Australian Bureau of Statistics figures show, even as a strong export performance, robust business investment and a jump in government infrastructure spending propped up activity.

Real GDP expanded by a soft 0.4 per cent in the three months to June, the ABS data showed, unchanged from an upwardly revised 0.4 per cent in the March quarter.

After accounting for the bounce in population growth thanks to a resurgence of migration over the past 12 months, real GDP per capita dropped by 0.3 per cent – the second consecutive quarterly decline that reflected falling living standards for many households even as the overall economy grew.

KPMG chief economist Brendan Rynne said the national accounts confirmed “what most households and businesses … are already feeling: that economic activity is flat and growth has largely stalled”.

Jim Chalmers, however, told a press conference in Canberra that the overall picture from the national accounts was “a steady and a sturdy result in difficult circumstances”.

The Treasurer said he still expected the economy to “slow considerably over the next year” as hundreds of thousands of mortgage holders shifted off ultra-low fixed interest rates, and the global outlook became fraught as China stuttered.

Nonetheless, he remained “optimistic” about the future, saying Australia “was one of the fastest growing advanced economies through the year to June”.

“We face these challenges from a genuinely enviable position. We have an unemployment rate with a three in front of it still, remarkably, (and) wages growing around their fastest pace in a decade,” Dr Chalmers said.

Opposition Treasury spokesman Angus Taylor said there was “nothing steady or sturdy about these numbers” and Australian families were working “more hours to keep their head above water”.

“It is very clear now that Australia is in a per-capita recession. The economy is shuddering to a halt,” Mr Taylor said.

“We’ve had two quarters now where growth per person is negative. Indeed, the only thing propping up this economy is record levels of population growth.

“Take that away and the economy would be well and truly in recession.”

While the national accounts suggested the economy finished the recent financial year in relatively good shape, the figures pointed to the growing financial pressure on households.

Homeowners shelled out nearly $83bn in mortgage interest repayments in the 2022-23 financial year, double the previous year’s bill, the ABS data revealed.

As surging energy and grocery bills, alongside soaring interest payments and rents, smash household budgets, consumption scraped higher by 0.1 per cent in the quarter, from 0.3 per cent in the previous quarter.

Unsurprisingly, Australians saved less, with the household savings ratio falling to a 15-year low of 3.2 per cent from 3.6 per cent in March after last peaking above 19 per cent in September 2021.

Australia’s trade performance remained a bright spot for the economy, buoyed by the rapid return of international students and a near 20 per cent jump in tourism exports in the quarter, as the number of Chinese visitors ramped back up.

There was also a further steep decline in labour productivity, with GDP per hour worked slumping 2 per cent to be 3.6 per cent lower on a year earlier.

CBA senior economist Belinda Allen branded the productivity result “a shocker”, as unit labour costs – which tend to match inflation over the longer term – jumped by 5.8 per cent in the 12 months to June. She said the slowdown in nominal GDP would eventually flow through to the commonwealth’s finances.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout