Veil of silence on Korean War fighters’ fate

The destiny of nine Australian combatants from the Korean War has remained unknown to their loved ones since 1953.

The Australian government has known for nearly 66 years that missing soldiers and RAAF pilots presumed killed in the Korean War were believed to be alive in communist captivity when the conflict ended in 1953, declassified records show.

One of the nine missing men, fighter pilot Don Armit, is the subject of disputed claims that he was mentioned in secret Soviet communications about captured Allied flyers and taken to Russia for interrogation after being shot down over North Korea.

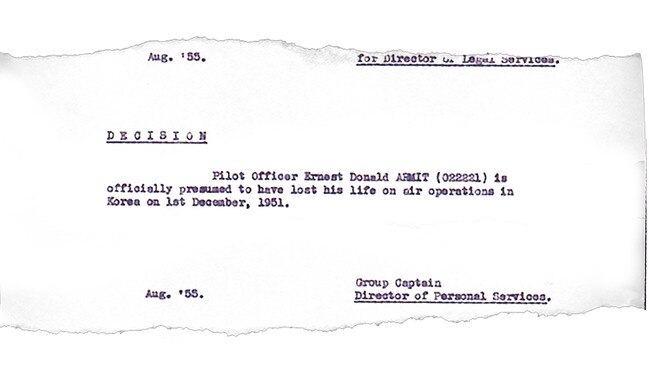

Despite the emergence of the new material, the RAAF is adamant there is no evidence to support a finding that any of the Australian MIAs survived the war as prisoners. The official record stands that they are missing in action, presumed dead.

And it rejects outright the possibility that Armit, 25 at the time he was lost in 1951, was handed over to the Soviets, insisting the “most probable conclusion” was he died when his warplane crashed.

“In the absence of further evidence, Air Force concurs with the US that the list of nine Australians ‘believed to be POW’ is not supported by any evidence,” the family of one of the missing men was informed this month, deeply angering them.

Philip Norrie, the Sydney GP heading the Armit family’s push for answers, said they were frustrated that the government had done “bugger all” to get to the bottom of what happened to the missing pilot.

“It’s still a mystery,” Dr Norrie said. “People contacted Don’s mother, Frances, for years telling her he was still alive, being tortured, and it drove her up the wall. Like anybody, we want closure.”

His wife, Belinda, who is Armit’s second cousin, said: “She never went out of the house. I think she really thought he would come home.”

Bit by bit, British and US archives have given up the secrets of what was known about the missing nine and the lack of effort by a supine Australian government to establish their fate at the end of the Korean War.

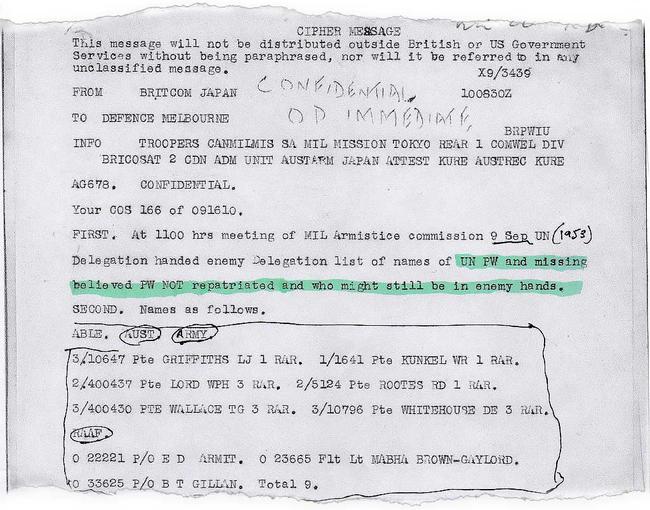

In late 1953, the British military command in Japan, Britcom, advised Defence in Melbourne that the names of the Australians “still in enemy hands” had been provided to North Korean and Chinese representatives involved in the negotiations to return POWs on both sides. The cable said the information had been exchanged on September 9, 1953 — 10 weeks after the armistice.

It named the nine Australians with their unit, rank and service numbers alongside British, Canadian and South African MIAs “believed” to be prisoners of war.

This was done under the auspices of the UN Command Military Armistice Commission. The list mirrors one that was prepared by US military intelligence and reported by the US Department of the Army Staff Communications Office in a secret document dated September 2, 1953.

It is not known whether this was shared with Australian officials, though some details were later reported in the Australian press.

The Britcom cable, however, is the first direct evidence that Canberra was formally made aware of the possibility that Australians could have been left behind in North Korea after the ceasefire came into effect on July 27, 1953.

Robert Menzies’s government evidently failed to act — either by taking up the case of the missing men or demanding that the Americans do so, given they called the shots during and after the Korean War, where the US-led coalition supporting the South Koreans fought under a UN mandate.

No effort seems to have been made at the time by Australia to establish the veracity of the intelligence used to put the lists together, which is now contested.

Instead, the running was left to the British, who concluded that the lists were “grossly inflated” and there were in fact only two pilots — one Canadian, the other British — whose plight was accurately depicted.

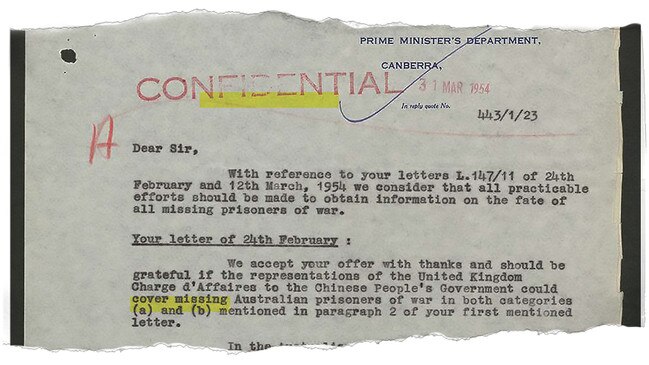

On March 31, 1954, the secretary of the Prime Minister’s Department under Menzies wrote to the British high commissioner in Canberra accepting the UK’s offer to make representations to the Chinese on the missing POWs.

The official, Allen Brown, also suggested the embassies of both Australia and Britain in Moscow approach the Soviets to secure any information about the missing men and that the Indian government be asked to play an intermediary role with the Chinese. Australia at the time did not have diplomatic relations with China.

“It is considered that no reference should be made to the medical condition or circumstances in which the persons were last seen, as such details might provide the communists with material to cover any wrongful act such as the killing of prisoners of war,” Sir Allen cautioned in the confidential letter.

In addition to Armit, whose Meteor jet fighter was shot down by Russian-made MiG-15s on December 1, 1951, RAAF pilots Bruce Thomson Gillan, 22, and decorated World War II veteran Mark Browne-Gaylord, 30, were listed as missing, presumed dead, after being lost on the same day in January 1952 air battles.

Among the six Australian Army MIA presumed dead but named as possible prisoners, Private Leslie John Griffiths and Private William Rudolph Kunkel were posted as likely killed during operations by 1RAR in November-December 1952; Private William Henry Lord and Private Thomas George Wallace of 3RAR were presumed killed in fighting on July 13, 1952; Private Dennis Whitehouse, also of 3RAR, was presumed killed on August 14, 1952; and Private Reginald Donald Rootes of 1RAR was seen to be killed in action on December 11, 1952, although his body was not recovered.

The quiet, determined courage of Armit and his fellow pilots is conveyed in a letter home to his cousin, Ted Chambers, in November 1951, eight weeks before he was shot down northeast of the North Korean capital, Pyongyang.

He recounted how the MiGs outperformed and outgunned the first-generation Gloster Meteor jets flown by the Australians, though “inferior pilots” were at the controls of the enemy planes.

“Their 37mm cannon is grimly fascinating to watch … when firing, it throws out a gout of flame about three feet in front of the nose of the aircraft whilst their 23mm’s give off a seemingly harmless twinkle,’’ the young man wrote.

On one mission, a cannon shell ripped through the port side of his Meteor, severing the cockpit heating line and a fuel pipe. “All this without exploding … I can’t understand how I didn’t get a fire with all that fuel thrown at a motor that had the taps wide open,” Armit marvelled.

His luck ran out on one of the blackest days for the RAAF’s storied 77 fighter squadron, a frontline unit that is today in the process of converting from F/A-18 Hornets to the stealthy new F-35 Lightning II.

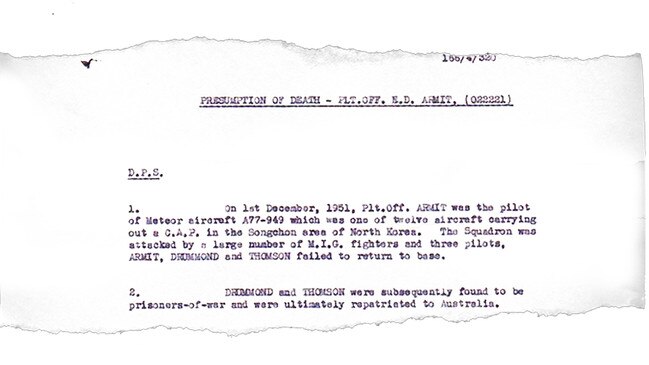

Armit, an admired flight leader, was lost with two other Australian pilots after the squadron was bounced by a swarm of MiGs. What they didn’t know was that they were probably up against crack Russian pilots who had been secretly deployed to bolster the North Koreans and their Chinese allies.

Flying officer Bruce Thompson and pilot officer Vance Drummond safely ejected and were picked up by the North Koreans, but Armit was never seen again.

Speculation that he survived the crash and ended up with the Russians has been kicked along by the emergence of a secret Soviet combat report sourced by the US Defence POW/MIA Accounting Agency, describing how the “flyer of a downed enemy Meteor was taken prisoner” on December 1, 1951, the day Armit and his squadron mates came to grief. This document, known as the Soviet #381 action summary, was forwarded to RAAF investigators and recently made available to the families.

It suggests the pilot was interviewed by Russians soon after he was captured. Innisfail lawyer Bruce Gillan, the nephew of Bruce Thomson Gillan, of 77 Squadron, who was shot down eight weeks later on January 2, 1952, is convinced the man could only have been Armit.

Mr Gillan says this is because neither Drummond nor Thompson reported encountering Russian personnel after they were eventually freed and, further, the Soviets had been at pains to keep secret the presence of their pilots in Korea. If they did question an Australian pilot, it was unlikely they would have allowed him to go, such were Cold War tensions.

“There was only one pilot interviewed by the Russians of the three shot down, so it has to be Armit,” Mr Gillan, 62, said.

His theory is rejected by retired RAAF wing commander Grant Kelly, who works with the air force’s Historic Unrecovered War Casualties section and liaises with the families.

In a July 10 email, he advised Ian Saunders, the son of a missing Korean War soldier not on the suspected POW lists, that the pilot described in the #381 action summary was more likely to have been Drummond, who had reported that he was “corkscrewing around” Armit’s plane prior to ejecting. “There is nothing to counter the 1955 Presumption of Death decision that Armit died in the combat action on 1 December, 1951,” Mr Kelly said.

See the document in full (PDF)

Citing a 1994 study by the Rand organisation, a think tank entrenched in US defence and strategic decision-making, Mr Kelly quoted the author, researcher Paul Cole, as concluding that Soviet intelligence services such as the then KGB did not take UN personnel on “one-way trips” to the USSR.

As for the other eight missing Australians named as possible unreturned POWs in North Korea, Mr Kelly said: “The 1994 Cole Rand report concluded the evidence of why personnel were placed on the 1953 UNCMAC list of ‘believed to be POW’ has not been located and may not exist.”

Away on a recovery mission for the military, Mr Kelly did not reply to questions from The Weekend Australian.

Mr Gillan is demanding that the Australian government, through Foreign Minister Marise Payne, approach the Americans to access the crucial intelligence.

“You have to go to the top of the tree,” he said. “There has to be documentation with some information on why my uncle and the other men went on that list. Now that information could have been erroneous. Fine. Show it to us and let us see for ourselves.”

Speaking on behalf of the Armit family, Dr Norrie, 66, said: “We would like to believe he died on site and wasn’t tortured. But unfortunately, anything is possible.”

In a statement, Defence said it was not known how the nine Australian names were added to the list of presumed POWs at the end of the Korean War and “extensive archival research has not yet confirmed” that process. “What is known is that it was no secret to the Australian government at the time, as formal advice was provided to Defence at the time the names were on the list,” it said.

“It was no secret to the Australian public, as the names of all nine men, classified as “missing, believed prisoner” were published as such in newspapers at the time.”

Senator Payne said: “The unknown fate of those missing in the Korean War continues to be a source of pain and frustration for their families.

“Australia continues to work closely with both the US and South Korea to uncover the fate of those missing in action to recover remains from the Demilitarised Zone and in North Korea.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout