Turnbull sees new opportunity to grow the US alliance

Malcolm Turnbull’s late-February visit to the United States has set the ground for fundamental change to our security alliance.

Malcolm Turnbull’s late-February visit to the United States has set the ground for fundamental change to our security alliance and Mr Turnbull’s emergence as a Prime Minister with solid national security credentials and a plan for stronger Australian defence leadership in the Asia-Pacific.

For defence policymakers, there is a heady mix. In Donald Trump we have (to be kind) a quirky leader who, despite his election rhetoric, is pressing for stronger alliance relationships in Asia.

In Mr Turnbull we have a Prime Minister worried about stability in Asia, wanting Australia to play a stronger leadership role in the region and with a blueprint for reshaping the defence and intelligence alliance relationship.

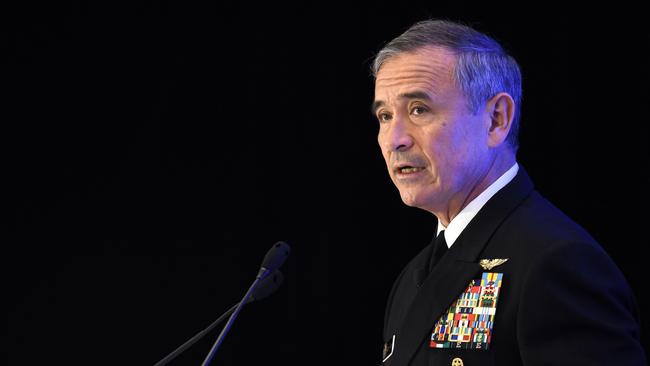

And in President Trump’s nominee as US ambassador to Australia, Admiral Harry Harris, chief of the US Pacfic Command, we have a whip smart, tough-minded and unafraid individual with the capacity to speak directly to the President and the Prime Minister.

Taken together, the strategic trends and combination of personalities steering the alliance suggest that we are about to see a fundamental remodelling of the relationship. There is no time to lose.

When Mr Turnbull became Prime Minister in September 2015, he was, to be frank, regarded by many in the national security business as flaky on defence.

Japanese and American colleagues pressed me for assurance that Mr Turnbull wasn’t soft on China and that, having never sat on the national security committee of cabinet, he would put the right priority on security.

When Mr Turnbull launched the defence white paper in February 2016, it wasn’t immediately clear the government fully understood what it was signing up to.

The classified work and key cabinet discussions on the white paper happened while Tony Abbott was prime minister. Mr Turnbull arrived fresh to the task and was within his rights to reconsider what was being put to him but the policy stayed the same on the fundamentals.

The white paper’s strategy to defend Australia is built around two central ideas, the first of which is a radical return to a forward-defence posture. In slightly coded language, the policy says: “We cannot effectively protect Australia if we do not have a secure nearer region, encompassing maritime Southeast Asia and South Pacific.’’

The government’s $200 billion plan for submarines, ships, aircraft, armoured vehicles and the rest will equip the Australian Defence Force to fight in “maritime Southeast Asia’’ – a region the rest of the world knows as the troubled South China Sea.

The other central idea of the white paper is the US alliance, which is not only Australia’s strategic Plan A but also Plans B, C and D. People have observed that the phrase ‘‘rules-based order’’ appears like a metronome in the white paper 56 times. That’s nothing: the United States is named on no fewer than 115 occasions.

The white paper sets out a step-change in the Australia-US alliance. If the plans are fulfilled we will have an ADF able to seamlessly operate with the American military, substantially boosting essential allied anti-submarine capabilities in the region and drawing great value from a shared intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance system. In every area, from Special Forces to amphibious strike, air combat, force projection and ballistic-missile defence, the Australia-US alliance would lift to a new level of integrated military capability.

To be clear, a dynamic alliance with the US doesn’t reduce but strengthens Australia’s independence. As Mr Turnbull said in the US the alliance “is a means for maximising our manoeuvrability and independence, not constraining it’’.

Whatever the reality at the time of the white paper’s launch, it’s clear that Mr Turnbull gets the central importance of the alliance now. Mr Turnbull’s recent speeches show that he is acutely aware of the deteriorating state of regional security and the need for concerted policy responses.

Speaking to the National Governors Association in the US on February 25, Mr Turnbull even hinted at the possibility that the target of spending 2 per cent of gross domestic product on defence by 2020 might not be enough. We are on track to reach that goal, he said, “and in these uncertain times we should all be thinking about what more we might contribute’’.

Mr Turnbull is also confident that he has established an effective relationship with Mr Trump. That famously testy phone call a year ago may well have been a blessing because it cemented in Mr Trump’s mind the idea that Mr Turnbull was a tough negotiator, focused on the art of the deal.

Mr Turnbull has adroitly followed that up by emphasising the so-called ‘‘hundred years of mateship’’ that’s claimed to mark defence co-operation between the two countries.

My own experience of shaping defence engagement between the two countries is that the reality of the business has less moist-eyed emotion and a sharper focus on the value of a dollar and the credibility that only comes from really turning up to do the hard yards in East Timor, Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria and wherever the next flashpoint may be.

This points to one of the risks in Mr Turnbull’s strategy. It’s welcome to hear the Prime Minister tell an American audience that Australia is committed ‘‘to a far more active role in shaping the future of our region’’, but now we have to deliver on the rhetoric.

It’s hardly surprising then that Mr Trump reportedly pressed Mr Turnbull to get Australia to do a freedom of navigation operation (FONOP) in the South China Sea, the point of which is to show China that Australia, along with most other countries does not acknowledge Beijing’s claim of sovereignty over reefs and reclaimed islands in the region.

To this point, Australia’s policy on FONOPs has been as spineless as the sea cucumbers that wriggle around China’s freshly-constructed South China Sea airbases. The government claims that our ships and aircraft do transit the region, but the only way to accurately show opposition to China’s claims is to sail within the 12 nautical miles sovereign zone of a contested island.

This Canberra has resolutely refused to do. In October 2016, when Labor pressed the government to authorise a FONOP, Foreign Minister Julie Bishop said that such a move would “escalate tensions’’. While the Obama administration could never work out how to respond to Beijing’s sovereignty grab in the South China Sea, the tougher-minded Trump administration has regularly sent aircraft carriers and other ships on FONOPS through the region.

Mr Turnbull has much to lose in terms of his newly-won alliance credibility if he does not authorise a FONOP now. It’s a pity that our tardiness in conducting a FONOP, which is very much in our national interest given the importance of the South China Sea as a trade route, means it will be seen by some as responding to alliance pressure.

Mr Trump’s wish to press China on freedom of navigation in the South China Sea is a positive affirmation of American strategic interest in Asia. Mr Turnbull said in Washington that Mr Trump’s “national defence strategy signals a reinvestment in American hard power and the alliance system which amplifies its reach. President Trump’s nomination of Admiral Harry Harris as ambassador to Australia underscores this message.’’

While China’s President Xi Jinping removes the last threadbare restraints to assuming an absolute personal dictatorship over America’s only ‘‘near-peer’’ strategic competitor, the challenge for those countries in the Asia-Pacific who won’t bend to this authoritarianism is to get our defence and security thinking in order.

What should Mr Turnbull do to start the process of alliance renewal? First it’s time to remodel AUSMIN, the rather genteel annual meeting between our foreign and defence ministers with the US secretaries of state and defence.

A six to eight-hour annual meeting will not aggressively drive the agenda for change. Mr Turnbull should propose an annual alliance meeting with the President to turbocharge alliance activity. AUSMIN should follow six months after that with a direction to push implementation across all aspects of defence and security.

Next, Mr Turnbull and Mr Trump should create a bilateral strategic innovation commission, bringing together smart lateral thinkers to identify the new technologies and approaches that will shape our military forces an intelligence apparatus into the future. Celebrating 100 years of mateship is all well and good, but a focus on the future is needed to blow some cobwebs out of the system.

Third, Australia and the US need to talk more about the strategic elephant in the room — China — and to make sure that we are on common ground in responding to Beijing’s persistent intellectual property theft and attempts to shape our internal political debates. There is a central role for our new Home Affairs department here.

Finally, as Mr Turnbull said in Washington, “we want the integration of our defence industry supply chains to match the interoperability of our armed forces’’. This is the key to sustaining high-technology military forces and getting it right requires taking another look at the mostly cultural barriers preventing genuinely closer co-operation between Defence and industry.

This is an ambitious agenda and one that needs broad bipartisan support because it inevitably will have to survive changes of ministers and governments. Mr Turnbull’s Washington visit shows that he now gets the importance of boosting the alliance and the signs are that the Trump administration agrees.

Peter Jennings is executive director of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute and a former deputy secretary for strategy at the Department of Defence.

More Coverage