Morrison reset Australian defence structure by planning AUKUS

What drove Scott Morrison to create AUKUS and ditch an agreement for French-built submarines for a nuclear option? Read on.

It was late into the afternoon of May 13, 2021, when Scott Morrison finally took his plan for AUKUS, which had been more than a year in the making, to the National Security Committee of cabinet.

While it was Morrison’s secret brainchild, it would never have been envisaged had he not already known there would be a receptive ear from Britain and the US, should Australia come calling.

British prime minister Boris Johnson was across the concept – having been briefed by his own defence chiefs. He had sent Morrison a cheeky text prior to the first official call to seal the deal: “I hear there is something exciting.”

But Morrison had resisted engaging in high-level discussions without the full knowledge of not only the defence and security apparatus but his most trusted political colleagues. Fresh from receiving approval to make the official calls that Thursday afternoon, Morrison and his treasurer, Josh Frydenberg, bolted to the House of Representatives chamber, where Labor leader Anthony Albanese was on his feet delivering his budget-in-reply speech.

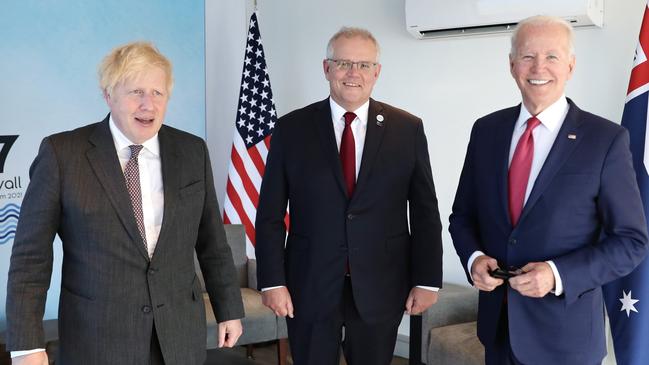

A few days later, Morrison phoned Johnson for the formal discussion. The British prime minister was as supportive as Morrison anticipated, and would be pivotal in setting up a historic meeting with US President Joe Biden in the weeks ahead, in which they would secretly formalise the most significant defence agreement since World War II.

Morrison and Johnson had joked that the first working name for AUKUS would be “Project Freedom”.

HOW IT UNFOLDED

An edited extract from Plagued, Australia’s Two Years of Hell – the Inside Story by Simon Benson and Geoff Chambers

The genesis of AUKUS traced back to an informal conversation Scott Morrison had with his defence adviser, Jimmy Kiploks, in late 2019, several weeks after Morrison’s August visit to the French town of Biarritz for the G7 summit.

He was interrogating Kiploks on the delivery of the myriad defence contracts he inherited as prime minister.

Some of the contracts had significant challenges. None more so than the $90bn French deal for twelve Attack-class subs, signed in 2016 by Malcolm Turnbull and then defence industry minister Christopher Pyne.

Morrison wanted to reassure himself of the commercial rigour around the project, with all its delays, jostling and cost blowouts.

Above all, he wanted to test whether it was still the right strategic decision. The reassessment of China’s gambit and Australia’s need for a revised defence strategy that swung the force posture away from the multiple theatres of operation it had been engaged in for the past two decades, and towards a more potent Indo-Pacific focus, had hardened.

Morrison asked Kiploks to make some discreet technical inquiries of Defence. He wanted to know whether there was any prospect of a nuclear-powered option with the US. And if so, how that could happen. Defence officials had discouraged both Morrison’s predecessors (Tony Abbott and Turnbull) from pursuing it because at that point there was no confidence the US would ever share its nuclear technology.

When Turnbull struck the French deal, the economic industrial imperative, and the importance of naval shipbuilding capability, was a big part of the equation. Sovereign capability was central to the vision.

But to Morrison, several years later, these considerations did not trump the strategic issues he saw Australia was now facing. Circumstances had dramatically changed by the time he found himself posing these questions. Not only had the great power competition accelerated but technology had also changed. Morrison’s primary concern was that the conventionally powered French submarine capability would be redundant by the time the vessels got wet.

Morrison had even more questions: what strategic benefits a nuclear-powered submarine platform would provide for Australia, and would Defence be prepared to have a good look at it?

Kiploks came back with an unexpected initial response: nuclear submarines were worth exploring. This was a significant shift in only a few years and Morrison later admitted he’d been surprised to hear Defence’s change of heart.

Surprise or not, the shift in thinking put in motion a series of secret negotiations that would crystallise Morrison’s overarching strategy and set Australia on a new course. A significant reason for the development was that a key technological and political barrier had been overcome: the new US nuclear reactor platforms required no servicing for the entire life of the boat. This meant Australia could itself operate a nuclear-powered naval fleet without the need for a domestic nuclear industry.

While the French also had a nuclear boat to offer, (Peter) Dutton, as defence minister, would later simply dismiss it, claiming the French nuclear option was “not superior” to the US/UK options.

The larger question was US willingness to share its tightly guarded nuclear propulsion technology. This had occurred only once before when, under the 1958 US-UK Mutual Defence Agreement, the US supplied a single nuclear submarine propulsion system to the UK under a broader nuclear technology-sharing pact.

‘HOLIEST OF HOLIES’

It was time to look at options. Defence Department secretary Greg Moriarty was asked to form a top-secret technical group advised by experts including former chief scientist Alan Finkel. Before long, it reported back that a nuclear submarine option might be workable, and continued to sift through mountains of detail.

It wasn’t until the Biden administration that any serious discussions were engaged in at a political level. This was not something Morrison had ever discussed with (Donald) Trump.

By early 2021, Kiploks and Morrison’s international adviser, Michelle Chan, began a dialogue with US and UK officials: Kurt Campbell, White House coordinator for the Indo-Pacific; Joe Biden’s National Security Adviser, Jake Sullivan, and; the UK Secretary of Defence, Stephen Lovegrove, who Johnson appointed as his national security adviser in March of that year.

AUKUS started taking shape for Morrison at the start of 2021, when it became clear Australia should be looking at capabilities beyond just submarines.

This included precision-strike guided missiles, cruise missiles, hypersonic missile capability, cyber warfare, undersea drones, space, artificial intelligence and quantum technology. Some of the missile technology on offer, including the Tomahawk cruise missiles, had been approved by the US more than a decade before but had fallen out of previous Defence white papers.

Morrison had come to the conclusion Australia was now shopping for something broader than just submarines, even though there was a view within Defence that it should limit itself to upgrading the submarine capability.

Reflecting that it had taken a year just to resolve the submarine issue, Morrison wanted to avoid future Australian prime ministers being saddled with the same limitations every time they wanted to do something innovative or add a new technological capability.

This was about getting in on the ground floor and going beyond the concept of a treaty.

When Morrison had specifications drawn up and costed for his vision, the price tag was hefty: an annual Defence spend above 2.5 per cent of GDP. If passed, it would be the highest Defence spending in Australian history.

After the US indicated it might be prepared to offer Australia the “holiest of holies”, as Morrison described the US nuclear submarine technology, he met with the chief of the Defence Force, Angus Campbell, and asked him bluntly: “Should we do this?”

“Yes, Prime Minister, we should do this,” Campbell replied.

Again, Morrison sequestered himself in his study to consider the relevant facts. Past assessments were that the French sub was the right sub, and the safest for Australian submariners: safety was always a major consideration.

Morrison, however, was now looking at Australia’s defences from different angles and three questions arose: If Australia stuck with a conventionally powered submarine, could its navy deal with a situation beyond the Indonesian archipelago? Did Defence have options that didn’t involve subs? And could the risk of armed conflict in the Indo-Pacific be managed without a strategic submarine capability?

The answers kept coming back to Morrison: “No.”

Morrison knew his expanded vision would get a positive reaction from Johnson and was convinced Biden would be amenable too. Thus began the pitch for a framework that would develop a cradle-to-nurse for not only the nuclear submarine project but other projects as well.

By the time Dutton had been appointed defence minister in March 2021 … much of the technical planning for the ambitious new project was already in place.

Morrison was then ready to formally take it to the National Security Committee, so as to brief other ministers on the plan and get approval to take the next step: to engage in the necessary political discussions with Johnson and Biden.

FRENCH FRUSTRATIONS

While all three parties to the discussions regarding a nuclear option kept the French government in the dark, there were growing and very public frustrations over the submarine contract with Naval Group, a majority French state-controlled company, with deliverables already overdue.

An early clue that the ground was shifting in Australia’s maritime defence arena came in early June. Moriarty revealed to a Senate estimates committee hearing that Defence had been working on other options in the event the French project fell over.

The French had been given plenty of hints that there were serious concerns with the project and those concerns had been raised for some time.

GAME-CHANGER

Biden’s international posture leaned heavily towards the Indo-Pacific, with his commitment to the pivot more concerted than (Barack) Obama’s. This was the impetus for reactivating the Quad.

Morrison was mindful that the last time the US went passive in the region, China built installations in the South China Sea. No one had stopped them.

Biden’s assessment was based on the US’s national and strategic interest. Its most important strategic focus was no longer post-war Europe. It was no longer the Middle East. The US had formed the view it was now the Indo-Pacific. The US was also reassessing what capabilities were required to address its interests there.

Australia’s role would be a critical element. That involved the concept of “integrated”, or collective, deterrence in which the US saw increased military integration with allies or partners in the region to address the direct – as well as the grey-zone – threats posed by China. The attraction for the US in a submarine deal under AUKUS was the networked capability it added to its Indo-Pacific interests via its closest ally in the region.

At the same time, the UK was looking for partnerships post-Brexit. It had already been expressing more interest in this part of the world. And Morrison believed a third partner in the arrangement was vital. By mid-June, the AUKUS deal was clinched after Morrison, Johnson and Biden met at the G7 summit in Cornwall. Three months later, it would be unveiled to the world.

‘QUELLE HORREUR!’

Morrison was prepared for a hostile reaction to the new defence initiative both from critics at home and from the French. For two days prior to the announcement of AUKUS on September 16, the French President had refused to take his calls.

Eventually Morrison was left with no option but to text Macron, attaching a letter that explained the decision. The reaction was both immediate and intense. France, incandescent with rage, recalled its ambassadors in Canberra and Washington DC.

When the Japanese had lost the original bid to the French, they too had been sorely disappointed but made no accusations of betrayal.

Undoubtedly, losing the deal was a blow to French pride and would come with substantial commercial fallout for French interests. Weapons sales to other nations was a major plank of France’s defence strategy: it had the double benefit of maintaining its sovereign defence manufacturing capability.

Morrison had balanced all this against Australia’s ability to respond to an existential threat. To him there was no comparison.

The argument that Australia should not have gone ahead with AUKUS to avoid upsetting France was naive. It boiled down to the national strategic interest, and here Australia and France did not necessarily align. For Morrison, the French being unable to see why Australia needed to head in a different direction reflected their lack of clarity on what the issues in the Indo-Pacific actually were.

LABOR ON BOARD

Labor backed the agreement on conditions, but they were conditions the government had already met: no nuclear weapon capability, no civil nuclear industry needed to service the boats and no clash with nuclear non-proliferation obligations.

Despite being from the Labor Left, (Anthony) Albanese was a staunch supporter of the Australia–US alliance. He recognised the political peril of opposing the submarine deal and AUKUS arrangement, conscious the ALP would inherit it in government.

With an election due within six months, Albanese would not allow Labor to be wedged on national security, defence and China.

Morrison also countered, including assuring Australians domestic political dynamics were not a consideration when he had embarked on the process. Nevertheless, he acknowledged that as well as solving difficulties, AUKUS had also presented new ones.

In a private moment with attorney-general Michaelia Cash, he confided, “Sometimes you have to decide whether there is a hill you are prepared to die on (politically)”.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout