Korea summit: families’ plea to bring our MIAs home too

The families of 43 Australian servicemen listed as MIA in the Korean War are hopeful they might at last get answers.

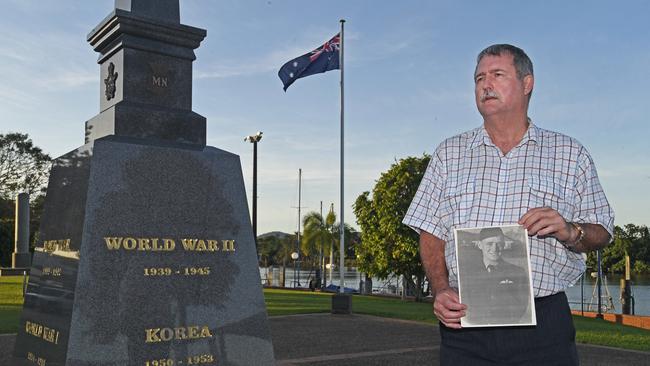

Craving to know what happened all those years ago to his dashing uncle over North Korea, Bruce Gillan and his family are hopeful they at last might get an answer.

Flying Officer Bruce Thomson Gillan — Mr Gillan was named after him — was reported missing in action after his RAAF Meteor was shot down in January 1952 near the port of Haeju, north of what’s now the demilitarised zone between the two Koreas.

The family were told the young pilot ejected from his smoking jet fighter, but Gillan’s parents and his only brother, Jim, Mr Gillan’s father, went to their graves not knowing whether he survived to be taken prisoner by the North Koreans and, if so, how long he had lived in captivity.

The families of the 42 other Australian servicemen listed as MIA in the Korean War endured the same torment — and now, finally, there’s the promise of emotional closure in the deal between Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un to roll the repatriation of the remains of US war dead into their historic peace plan.

GRAPHIC: Aussie diggers missing in action in Korea

Mr Gillan, 61, is hoping that Australia can piggyback on the tentative denuclearisation agreement reached by the US President and the North Korean leader on Tuesday in Singapore to end the uncertainty that has haunted the family for two generations. The call for closure has been taken up by others in the same harrowing predicament.

Former veterans’ affairs minister Stuart Robert, who has taken up the campaign by the families of the Korean War MIAs for answers, said the wheels were already turning for Australia to join the US and get boots on the ground in the communist North to find our war dead.

He spoke yesterday to Foreign Minister Julie Bishop about having the Americans extend the deal to cover Australia’s MIA. “I simply said to her, ‘Jules, we need to be in that discussion’,” Mr Robert told The Australian. “And she said, ‘Yep, we are already there … we are on it.’ Julie was ahead of the curve on this, to her credit.”

Ms Bishop later revealed she had made “numerous representations” on the issue, but none had been acknowledged by the North Koreans. “The fact that it was raised by President Trump and it has been agreed by North Korea gives us some hope that Australia will also be able to make representations to North Korea for the return of our war dead,” she said.

But Veterans’ Affairs Minister Darren Chester sounded a cautious note. “I think it gives some hope. It’s a step in the right direction, but it’s no reason for us to think it’s going to be easy from here on in,” he said.

Flying Officer Gillan, 22 at the time he went missing, was one of 18 Australian pilots who disappeared over North Korea or over the sea off the hermit kingdom during the bloody 1950-53 war that claimed 339 Australian lives.

All but one of the army’s 22 MIAs, including Ian Saunders’ father, John, were lost in the DMZ that still separates North Korea from the South. Two MIAs were navy personnel while the 43rd missing man, John Rodgers Hall, disappeared from a troop ship en route to Australia.

Mr Gillan said his uncle’s death cast a long shadow over the family. “I can tell you that at a very young age I could work out what my father was doing: he was trying to compete with the ghost of his lost brother in their mother’s eyes,” he said. “It was as if he was always trying to make up the difference or do better to please her because he was gone.”

On the day Gillan went missing in 1952, Mr Gillan’s father had an experience that would stay with him for the rest of his life. “Dad was at home with his mother, my grandmother, and he thought he heard someone call out, ‘Jim, I need you’,” the Innisfail solicitor recalled.

“He went around and asked her, “Mum, did you want me?’ And she said, no.

“Then, two weeks later they got the communique that Bruce had gone missing in action at that precise moment. It was chilling and it just added to the sense that they needed to find out what had actually happened to him.”

In addition to being named after his uncle Bruce, who had been vice-captain of Canberra High School and played rugby for the First XV before joining the RAAF in 1949, Mr Gillan obtained his pilot’s licence partly “to understand more about him”, he explained yesterday.

His uncle’s war record was impressive. He had flown 63 missions before taking off on the fateful January 27, 1952, sortie from Kimpo airfield near Seoul. He and his wingman strafed the North Korean air base at Chujin and were following the railway line towards Haeju when the anti-aircraft fire opened up, hitting his plane. Smoke was seen billowing from the stricken jet as it lost height, with the young pilot radioing that he would try to make it back to base.

When his wingman drew alongside, the cockpit was empty; Gillan had evidently ejected. A subsequent aerial search of the snowy landscape failed to find any trace of him. Mr Saunders said his father, Private John Saunders, was one of 13 soldiers with 3RAR killed or taken prisoner on January 25, 1953, while patrolling on the North Korean side of the DMZ. It was his fifth birthday.

Now 70, Mr Saunders co-ordinates the effort by the families to keep the issue alive.

He has never given up on finding out what happened to his dad, and yesterday wrote to Chief of the Defence Force, Air Chief Marshal Mark Binskin, to urge that Australia join the US repatriation mission.

Mr Saunders believes his father’s remains may be in an unmarked grave in the British Commonwealth section of the UN war cemetery at Pusan in South Korea, and he has campaigned for those graves and unidentified remains held by the US military in Hawaii to be DNA tested in case any of the missing Australians are among them.

“It’s phenomenal,” Mr Saunders said of the agreement between Mr Trump and Kim. “I have always stressed the point that we must exhaust all avenues in Hawaii and Pusan and, when that happened, we’d know that the missing remains must be in North Korea. Now, all the bases can be covered.”

Mr Robert said Australia had had no formal diplomatic contact with North Korea since it closed its embassy in Canberra a decade ago. But while he was minister, the Defence Department had sent to the Chinese, who entered the Korean War late on the North’s side, details of the Australian MIAs in the hope that leads could be turned up. DNA data had also been collected.

“We did all we could to get ready for this moment,” an enthusiastic Mr Robert said. “So … we are reaching out very strongly to the US … to say, hey, we want to be involved, we want to be there with our people, with our lists, to look for these Australians that we have not had the opportunity to bury properly.

“It’s very significant for the families who have been waiting all this time.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout