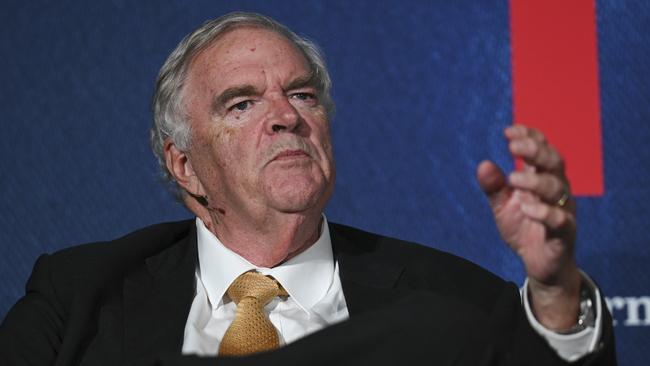

Defending Australia: Kim Beazley says Australia can no longer defend itself without US

Kim Beazley says Australia’s military could not defend the nation from invasion without the US, in a backwards step from the time he was defence minister.

Former Labor leader Kim Beazley says Australia’s military could not defend the nation from invasion without the US, in a backwards step from the time he was defence minister in the Hawke and Keating governments.

Addressing The Australian’s Defending Australia summit in Canberra on Tuesday night, Mr Beazley said: “We could not defend ourselves now without the Americans. When I was defence minister, absolutely we could defend ourselves.”

But Mr Beazley, a former ambassador to the US, also said Washington had “never in my experience been more dependent on Australia”. He said the American defence budget was stretched while Russia’s spending on defence had grown back to the level during the Cold War. He said Australia should focus on transforming its air bases across the north in a way that might be able to assist US deployments, and also reduce American reliance on China for critical minerals.

“We have enormous amounts of critical minerals,” Mr Beazley said. “Take battery minerals. We have twice the reserves of China.”

Delivering a keynote speech at the summit, Defence Minister Richard Marles said AUKUS was essential to defence strategy, as China was trying to “shape the world around it”. Mr Marles said principles such as freedom of navigation were being challenged by Beijing’s new-found ambitions, which were injecting a “greater sense of strategic contest” into regions including the Pacific islands.

Reflecting on his time in the US earlier this year, Mr Marles said there was increasing awareness of the “flash point” in which the world now found itself.

“We sit here tonight with the sense that escalation is possible,” he said. “We face ... the most threatening strategic circumstance since the end of World War II.”

Also at the summit, former Defence Department head Dennis Richardson warned there was “no real consensus” on defence “across the body politic” including the two major political parties. The former head of ASIO and a previous Australian ambassador to the US, said it would “take the body politic to be equally committed” to realise the AUKUS vision. He also warned neither side of politics was being “entirely honest” about how much defence spending would need to increase to make nuclear submarines a reality.

Mr Richardson echoed comments from Paul Dibb – seen as the father of Australia’s modern defence policy – that the defence force was too small. Professor Dibb, a former Defence Department deputy secretary, said Australia only had a “very professional ... peacetime defence force” rather than one ready for a war era.

South Australian Premier Peter Malinauskas said at an earlier session of the summit that AUKUS was at risk of being undermined by the competition between federal Labor and the Coalition to slow the immigration rate.

The South Australian Labor leader said proposed migration cuts overlooked the need for a massive influx of skilled workers to “backfill” positions vacated by Australians who were needed to build nuclear submarines.

He said South Australia alone needed to double the size of its defence industry workforce to at least 30,000, to be in a position to build the submarines in Adelaide.

While workers from non-AUKUS countries will not be able to work on the submarine program for security reasons, Mr Malinauskas said skilled foreigners would be needed to fill shortfalls across the economy.

“We need sparkies, we need plumbers, we need fitters, we need turners. We probably need butchers, bakers and candlestick makers,” Mr Malinauskas said.

“And as we seek to recruit those from existing industries, who is going to backfill that labour?”

Labor unveiled deep cuts to immigration numbers in the May 14 federal budget, pledging to wind back the net overseas intake from 395,000 this financial year to 260,000 in 2024-25, and then 235,000 in each of the following two years.

Peter Dutton vowed to cut even harder, reducing net overseas migration to 160,000. The promised cuts have been driven by housing shortages in capital cities that have driven up rents to levels beyond the reach of everyday Australians.

Mr Malinauskas said Australia had a housing problem, not an immigration problem, “and it is incumbent upon each and every one of us to make sure we focus on the main game when it comes to increasing housing supply, rather than a retrograde step to a policy debate that leads us nowhere”.

“So I will say to my Canberra colleagues that AUKUS must be a consideration in deliberations over Australia’s skilled migration program,” the Premier said.

British High Commissioner Vicki Treadell warned the Albanese government it was “no time to nick a few Brits” to build Australia’s submarine workforce.

“This is not the time for poaching, otherwise you will not get what you want,” Ms Treadell told the summit.

“Because you will strip out our capability to transfer that very knowledge and skills. This is a joint endeavour to grow our industrial base. This means growing the talent together.”

Ms Treadell said AUKUS was a statement by Britain of its “absolute trust” in Australia, opening the way for the UK to share 70 years of expertise in building nuclear submarines.

“So when people talk about joint venture, it will become one in the future. But it begins by what we transfer to you,” Ms Treadell said.

“But more than that, AUKUS must be a consideration in just about every area of policy.

“When we think about housing, what does it mean for AUKUS? When we think about infrastructure, what does that mean for AUKUS? When we think about education, health and innovation policy, what does that mean for AUKUS?”

BAE Systems Australia chief executive Ben Hudson said there were “a lot of skills that will come overseas” for AUKUS agreement. “There will be an influx... there has to be,” he said.

Opposition defence spokesman Andrew Hastie warned that “if we fail to maintain the bipartisan position on AUKUS then AUKUS will fail”.

Mr Marles said Australia, as a middle power, was “never going to be a peer competitor or a peer of China or the United States”.

“That is obviously not a strategic problem that we are seeking to solve,” he said.

But he said that was not to say Australia would be irrelevant in the context of a conflict. He said the nation needed to think about the Defence Force in a world that might be “far less certain”.

The key question was how Australia would create a “defence force that enables us to resist coercion”.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout