Criminal justice system faces trial as Diggers investigated for ‘war crimes’

The AFP will need a team of specialist investigators as it prepares for the first prosecutions on home soil of alleged atrocities by Australian troops.

The Australian Federal Police will need a team of specialist investigators as they prepare for the first prosecutions on home soil of alleged atrocities committed by Australian troops at war.

Former NSW deputy police commissioner and international war crimes investigator Nick Kaldas said the plethora of new criminal inquiries stemming from alleged crimes committed in Afghanistan would take police into new territory.

“I would suggest that the AFP, which has considerable experience, may need to look outside their own organisation to more traditional homicide investigators who have different skills in homicide, forensics, evidence collection and cognitive interviewing as well as people,’’ Mr Kaldas told The Australian.

Mr Kaldas’s remarks come as the AFP gears up to investigate a string of potential war crimes committed by Australian soldiers in Afghanistan.

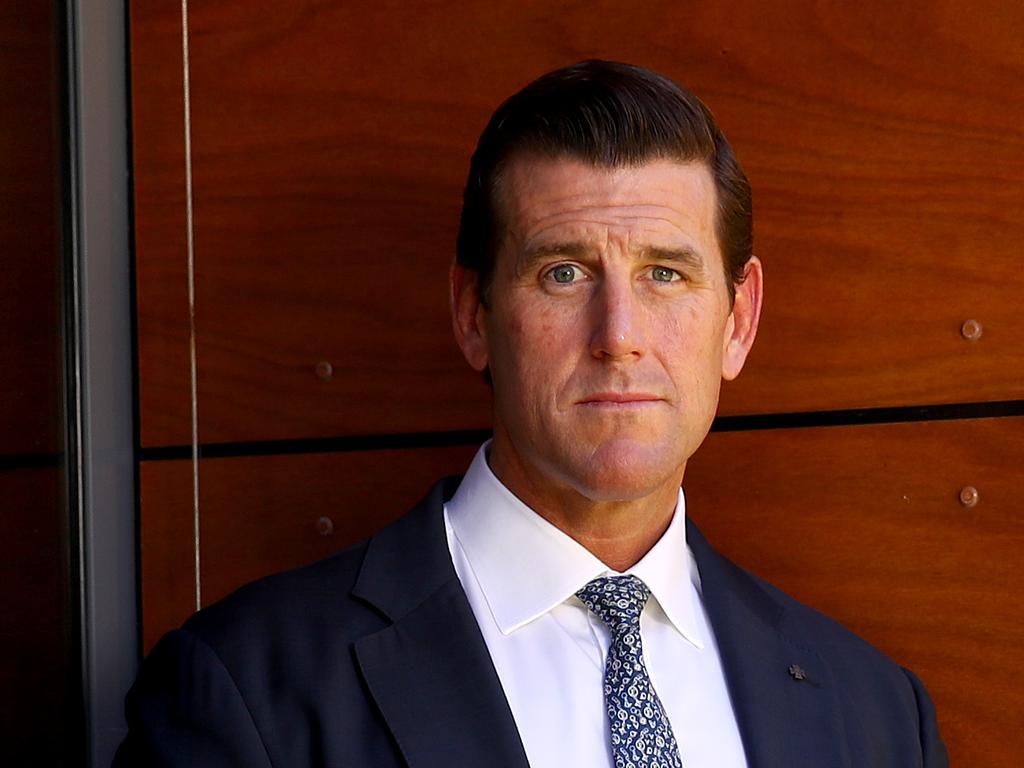

The AFP is investigating two alleged war crimes: the case of Victoria Cross recipient Ben Roberts-Smith, accused of ordering the execution of an Afghan prisoner, and that of “Soldier C’’, a Special Air Service Regiment operator who was filmed shooting an unarmed Afghan as he lay prone in the grass in May 2012.

Mr Roberts-Smith has not been charged and vehemently denies any wrongdoing. Soldier C has yet to publicly respond to the claims.

Regardless of the outcome of the cases, more investigations are likely, with the four-year military inquiry into possible war crimes expected to implicate other soldiers. The cases, when they come, will test the criminal justice system and require it to do something it has never done before: prosecute an Australian soldier for a crime committed in the service of his country.

University of Tasmania dean of law Tim McCormack, an expert in war crimes cases, said while war crimes prosecutions had occurred sporadically throughout Australian history, he could not recall a single instance where an Australian soldier was tried in a domestic court for breaching the laws of war.

“I’m not aware of any since Breaker Morant in the Boer War,’’ Professor McCormack told The Australian, which has spoken to lawyers, investigators and former military officers to examine the difficulties associated with investigating and prosecuting wartime atrocities. They point to problems gathering evidence in war zones, the unreliability of local witnesses and an untested criminal code.

Rodger Shanahan, a Middle East expert at Sydney’s Lowy Institute and a former military officer who has conducted operational inquiries in Afghanistan, said while he would not be surprised if Australian soldiers were charged with war crimes, “the prospect of success would be difficult’’.

“The difficulties are going to be getting reliable witness accounts, particularly with the passage of time,’’ he said. “It’s difficult to get reliable eyewitness accounts. You get people who say they were eyewitnesses but how do you prove that to be the case?’’

Mr Kaldas, who led the international investigation into the 2005 assassination of Lebanese prime minister Rafik Hariri, said even establishing the identity of witnesses could be difficult in countries where birth certificates are not universally issued. Cultural nuances, translation difficulties as well as coercion from hostile forces — in this case the Taliban — could also distort evidence, Mr Kaldas said.

“It many cases it may be rude not to answer so they give you something that’s not truthful,” he said. “In most Middle Eastern cultures it’s rude to refuse.’’

Mr Kaldas said that in most homicide investigations a witness’s story must be reconciled with the physical landscape, something that was not always possible in a war zone. “Somebody might say they saw something occur at a particular place and you get there and it’s not physically feasible. It’s quite important to have a look at where things are alleged to have occurred,’’ he said.

Both men agreed police would need to lean heavily on insider accounts from within the army, although Mr Kaldas said this was not without difficulty either.

In the case of the SASR, which has been riddled with jealousies and infighting, picking apart personal agendas could be particularly treacherous.

“It is absolutely incumbent to factor in people’s motivation, perspective and their agenda. That’s not to say you doubt their veracity, it’s just a duty on every investigator to factor in where is their evidence coming from?’’ he said. When charges are filed, they will be prosecuted under the Division 268 of the Commonwealth Criminal Code, an area of Australian law as obscure as it is untested.

Under Division 268, Australian soldiers serving abroad can be tried for crimes that would have been illegal had they occurred in the Jervis Bay Territory, on the couth coast of NSW, which, in a hiccup of Australian history, was surrendered to the commonwealth in 1915 and which now falls under the legal jurisdiction of the ACT.

The crimes include murder, inhumane treatment of a prisoner or civilian and killing a person hors de combat — after the fight is over. They mirror offences described in the Rome Statute, the body of law that gives force to the International Criminal Court, to which Australia is a signatory.

Most offences carry a prison term of 25 years to life. Any charge must be endorsed by the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions and authorised by the attorney-general.

If Australia does not properly investigate allegations on its own, it opens the way for the ICC to conduct its own criminal probe.

ANU international law professor Don Rothwell said trying these offences would test the legal system as much as it would test the police. “It’s decades since we’ve seen war crimes prosecutions in Australia,’’ he said. “There’s no corporate knowledge.’’

The 2011 trial of two Australian commandos accused of manslaughter after a grenade attack on an Afghan village that left five children dead, is about as close a modern precedent as you’ll get.

The trial was discontinued and, unlike the cases currently with the police, were filed under the Defence Force Discipline Act, the military’s own code of justice.

Professor McCormack said the last war crimes prosecution in Australia was the case of Ivan Polyukhovich, a Ukrainian migrant charged with participating in the mass execution of 800 outside a small town in northern Ukraine during World War II.

On the face of it, the case against Polyukhovich was strong.

Witnesses gave detailed accounts of the massacre that were backed by forensic evidence. One witness spoke of a victim with a prosthetic leg, a find that was corroborated during the excavation of a mass grave.

But it was not strong enough. Nine weeks after his trial began in April 1993, Polyukhovich was acquitted.

Before that, Australia had conducted 300 war crimes trials from 1945-51, mostly against Japanese soldiers. The trials were conducted in Morotai, Wewak, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Labuan and Manus islands.

None involved Australian defendants. The last Australian to be tried for war crimes committed during service appears to be that of Harry “Breaker’’ Morant.

In 1902, Morant and his co-accused, lieutenants Peter Handcock and George Witton, were found by a British court martial to have executed 12 Boer prisoners of war. The resulting sentence, death by firing squad, provoked an outcry in the newly federated Australia, no doubt foreshadowing the controversy that is sure to arise once the Australian legal system moves against its own.