Anzac Day: the indigenous fight after war to find lasting peace

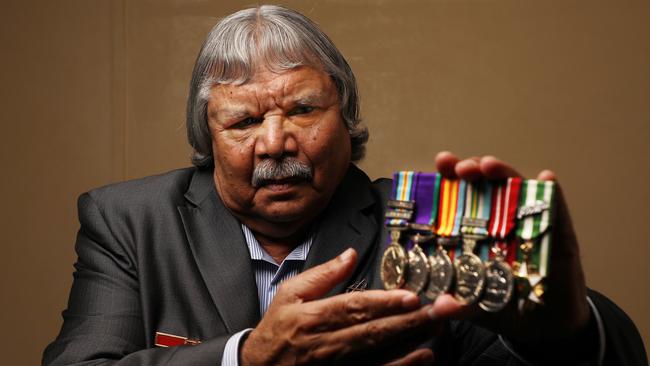

War has many complexions, and Aboriginal Digger Dave Cook has seen more of them than any man or woman deserves.

War has many complexions, and Aboriginal Digger Dave Cook has seen more of them than any man or woman deserves.

Taken from his parents as a child, and put into the Stolen Generations brutality of the Kinchela Boys Home in northern NSW, Cook began a long series of lessons about self-identity through an institutional war being waged on indigenous Australia.

Even today, he’s furious about it, in the contemplative kind of way that only age and reflection can bring. Kevin Rudd’s 2008 apology for the damage it caused he holds in utter contempt: “Any man can get up and say sorry for this and that, but the actions he took afterwards were next to nothing.”

Cook came to think of himself as not even really Aboriginal, and by the time he signed up to the army, serving as an engineer in Borneo during the Indonesian Confrontation, and then two tours in Vietnam, there was little difference in his mind between black and white.

On his discharge, things changed for Lance Corporal Cook. Post-traumatic stress disorder and the loss of a regulating force that had governed almost his entire life saw the start of a new war.

This one could be characterised as Cook versus the state, and — with its defining feature being a total of about six years’ jail for violent crimes — it’s fair to say the state was winning.

Cook says he was targeted. “When I got out of the army, I discovered the lie about being black and white, which is that the ones with the power to define which one you are the law, the police and the politicians,” he says.

“They were trying to knock me down to be the Aboriginal they said I was, and they did anything they could to put charges on me.”

There’s an irony in the fact his years of having the ability to love beaten out of him, starting at Kinchela and continuing on the battlefield, were linked to Cook’s redemption. Released from jail, he reconnected with the siblings who had been scattered from their parents under government policy.

Now 72 and settled in Raymond Terrace near Newcastle, he credits that reunion with turning his life around, although he freely admits relations with his own children are difficult.

“It’s a bit because of both my childhood and my Vietnam trauma,” he says now. “Everything is thrown in together, but it’s mainly because I’ve got no love in my body. I can’t love anybody; I’ve got no feelings for anybody.”

Love, though, is different from compassion, which is what drove him in recent years to put his army engineering skills to work on a volunteer landmine removal program in Cambodia.

These days, Cook’s wars are in the past, in memories shared with old comrades on Anzac Day. But it’s been a long fight to get there.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout