Death-rolled by a crocodile and for the first time, telling the tale

Johnny Banjo escaped a crocodile’s jaws of death after minutes of wrestling for his life. After poking the crocodile in the eye, Banjo grabbed his shirt and a loose can of beer before legging it on land. As it turns out, crocs are fast there too.

Stories don’t end when they hit the news. For The Australian’s 60th birthday, Fiona Harari retraces a story for each of the past six decades.

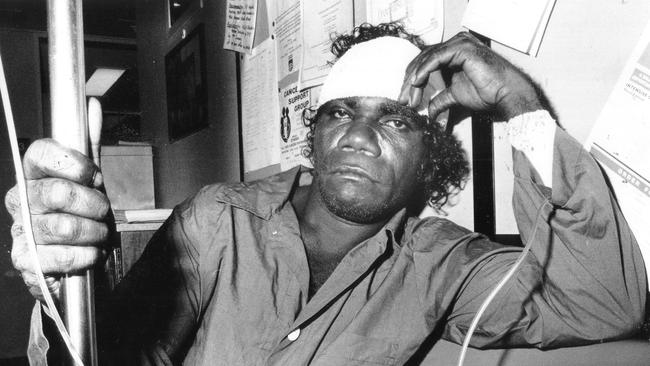

The story of Johnny Banjo’s life can be read across his body. His flowing white hair hints at the 68 years since he was born at the NT’s Tipperary Station, a massive pastoral land near the top of the continent.

The scars across his chest, which he calls his “dreaming”, date back to his childhood, when he was taken, aged five, to the Daly River mission to be schooled in the ways of another world, and his strong hands are a legacy of the years he worked as a carpenter.

But it is the pronounced gouge in the middle of his forehead that tells the most unexpected tale.

For 34 years, it has been a constant reminder of an otherwise unexceptional day when an enormous black crocodile grabbed him by the head and hurled him into a death roll.

“I think the croc saw me from far away,” Mr Banjo says now from his small home near the Daly River, the setting for much of his life, and the backdrop to the event that nearly ended it.

Growing up at the riverside mission, the nearest coastal swim a long and mostly inaccessible drive away, going for a dip locally didn’t always seem as hazardous as it does today. Crocodiles were a threat, especially after rains, but they could also be shot legally, and often were.

Locals like Mr Banjo were still wary of them.

“They tell us (to be) watching out for them crocs, don’t stand on the edge of the water or a billabong; there’s something in the water.” But only so much.

More than a few slayings acted as a safety net and a confidence booster: some residents of Nauiyu recall swimming carnivals held in the nearby Daly River.

So Mr Banjo was not overly concerned about anything lurking in the water when he decided to enter it late one afternoon at the start of 1990, on his way home from the pub. As he says: “We used to swim before – but there wasn’t any crocs before.”

Reports would later assert that he was only washing his face. He maintains now that he actually went for a swim late on that wet season day, discarding his shirt by the river bank, plunging into the refreshing water and then briefly lying on a log when he felt an excruciating blow to the back of his head. “I thought someone grabbed me from behind. Then I put my hand around …”

To his horror, he discovered that he was in the clutches of a 3m crocodile, its massive jaw clamped on to his head, with several enormous teeth digging deep into his forehead.

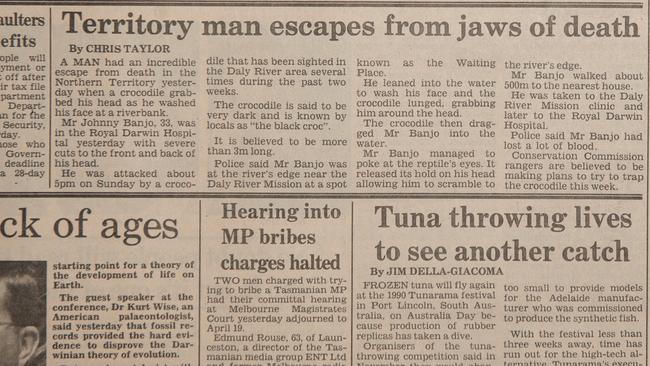

In intense pain, bewildered and unable to see the beast because it had attacked him from behind, Mr Banjo was thinking only about how to escape from what The Australian would later headline as the “jaws of death”.

“It took me down from the log and took me to the middle of the water and we started wrestling,” he recalls of being dragged under the river, his bloodied head remaining painfully in the croc’s clasp.

“We went to the bottom (of the river). I put my foot on the ground and it took me back up – so I could breathe again. Then he took me back to the other side of the river. He tried to death roll me.”

Because crocodiles cannot chew, they perform a frenzied manoeuvre to break down their prey, as Mr Banjo experienced over several frightening minutes.

He attempted to save himself by grabbing on to some low hanging tree branches, but was overpowered. “He tried to bang me on the tree. And he took me back in the middle (of the river) again so we were wrestling and twisting.”

Eventually Mr Banjo managed to move an arm behind him. “I found an eye – and I poked.”

Having been struck in one of its most vulnerable areas, the crocodile dropped its prey.

“It released its hold on his head, allowing him to scramble to the water’s edge,” The Australian reported of Mr Banjo’s escape on Tuesday, January 9, 1990.

That was not the end of his terror. Shaken and bleeding badly, he found the river bank, hoping to outrace the predator on dry land but the crocodile reached for him again, swinging its tail with a mighty thwack.

This time, and only just, the reptile missed. “So I got my shirt and a loose can of beer and I took off.”

He staggered a few hundred metres to the local clinic and later that night, with severe lacerations to the front and back of his head, he was transferred to Royal Darwin Hospital, his wounds comparatively minor given the extent of his ordeal.

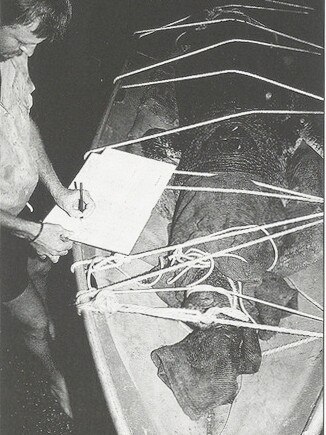

Around that time, a floating cage trap was baited in the Daly River, and Ross Belcher, the head wildlife ranger for the NT’s Conservation Commission, was summoned to remove the beast.

“I remember we were saying how ridiculous it was and totally avoidable,” says the now NSW-based Mr Belcher, 70, initially siding more with the reptile than the human who had opted to dip into its territory. “Crocs are fairly predictable; you know where they are,.” he said.

For this specialist called to capture the rare and territorial black crocodile, however, the high jinks were not over. Although he would eventually spend 16 years catching and tracking crocodiles in the NT (“We were pretty busy”) before heading to Antarctica and later working with wildlife in other parts of Australia, Ross Belcher still remembers this particular specimen.

For its successful removal, it needed to be captured in the floating trap, removed from the cage and strapped to a board – sometimes with a series of car seat belts – before being sedated and transferred to Darwin.

Wildlife, however, is not always compliant.“We were getting it out, we had it tied up by the snout and it broke loose and chased me around a tree.”

It was a narrow escape. With the score two-nil in favour of the humans, the crocodile was eventually sedated and taken to a breeding farm in Darwin. By then, Mr Banjo was recovering, although decades on the scars of that day still linger in multiple ways. He remembers, still, his sense of fear, the terrible thrashing, and the horrendous breath of the beast in whose clasp he was so terrifyingly held.

He has remained in Nauiyu, near the Daly River, in the years since, working as a carpenter and raising a family but he has not fished again in the decades since he returned home from hospital in Darwin, opting to let others catch his dinner. “My old lady used to fish for turtles and barramundi,” he said.

And mostly he has avoided swimming, going for the occasional dip only when others entered the water before him. “Every time they tell me to go for a swim, (I say) ‘No, I’m alright’.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout