Coronavirus and the slippery slope for civil liberties

The most radical assault on our civil liberties is raising concerns.

It had an innocuous title: “Keeping the tools we need to continue the coronavirus fight”.

But the statement from Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews, that he would seek to extend state-of-emergency powers by a year, has become a lightning rod for fury at his heavy-handed lockdown measures.

Civil liberties have fallen this year as quickly as the virus has spread.

A state of emergency was first declared in Victoria on March 16 to support two measures: a ban on mass gatherings and self-quarantine for returned travellers.

Now, Melburnians can leave their homes for only one hour a day, they can travel only 5km, they still face an 8pm curfew, they can visit their workplace only if it is on a “permitted” list and they can have police enter their homes without a warrant. There has been no effort to pare back any of the restrictions despite daily new COVID-19 cases dropping from a high of 692 cases on August 4 to 148 on Tuesday.

There have been other, quieter assaults on civil rights.

Military drones would have been used to spy on people if Victorian police had their way. When Defence rejected the request, police used their own drones to monitor outdoor areas.

Melbourne journalists have had to log the places they visit and the times as a condition of their “permitted worker permit”, causing concern about protecting confidential sources.

Of course, the virus is not confined to Victoria. Since the pandemic took hold in mid-March across the nation, state borders have slammed shut, Australians have been banned from travelling overseas and parliamentary sittings have been reduced drastically.

Legal experts do not take issue with what decisions have been taken in the interests of protecting the population; that has been more a question for health and economic experts. Rather, they have serious questions about how the decisions have been made and the lack of opportunity to scrutinise the most radical assault on human rights in Australian history. Some worry about setting a precedent that could make it easier to wind back rights in future.

Constitutional law professor Cheryl Saunders is in her mid-70s and lives in Melbourne. She wholeheartedly supports strong measures to protect health.

“Frankly, I was really worried as the numbers started rocketing up,” she says. “If I’ve got a health professional who looks trustworthy who says it would be good to have a night-time curfew for six weeks, frankly that’s fine by me.”

Saunders nevertheless believes that when the dust settles, it will be time to have a good, hard look at emergency procedures. She says if Australia were more used to emergencies it would have better accountability mechanisms built in to its processes. The “most obvious” would be to include a greater role for parliament, she says.

“If we lived in a country that was a bit more familiar with the concept of emergency we would probably have procedures that involved legislatures to a greater extent than we do,” she says.

“Where would the legislature come in? We need to think about that … But I think the answer lies in at some stage requiring some sort of parliamentary authorisation for renewing the emergency at least. Maybe something more than that, and maybe something more nuanced,” Saunders adds, pointing to New Zealand, where a powerful parliamentary committee, chaired by the Opposition Leader, was set up to scrutinise the government’s pandemic response when parliament was suspended. “But that’s the obvious way to go I think.”

A state of emergency in Victoria, which gives Chief Health Officer Brett Sutton extraordinary powers to impose the lockdown and rules such as mask-wearing, can be extended by four-week blocks but only for a maximum of six months. Andrews wants to extend this time limit to 18 months

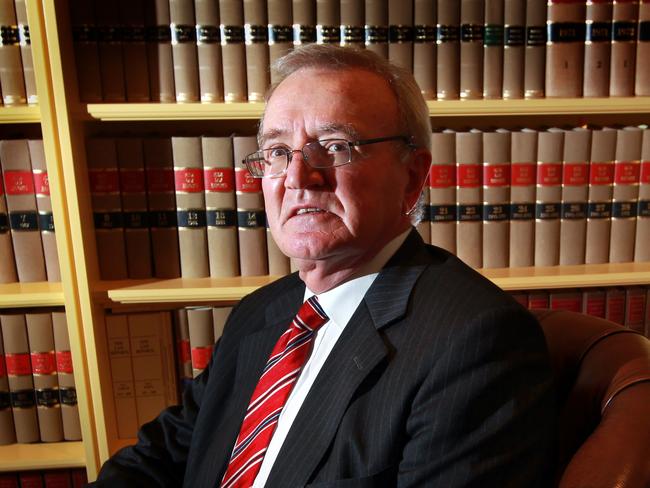

Rule of Law Institute Australia president Robin Speed is strongly opposed to the limit being extended to 18 months and is appalled by the lack of checks and balances applied to measures such as Melbourne’s curfew and 5km travel limit. He says health advice should have been released to justify the steps and the rules debated in parliament.

“Who says 5km is reasonable?” he says. “Where is the evidence? If you had to debate the matter in parliament, you would expect someone to stand up and say we think it’s necessary for health reasons, this is what our expert says and 5km is good, not 6km or 7km.”

The 76-year-old, who has cancer, says the nation’s leaders were meant to be focused on caring for vulnerable people like him.

“The worst thing for an old person is to die alone. Should an old person die alone, away from their relatives or not?” he says. “It’s a really major issue for me and anyone my age. If you come along and ask me, I would not want that to happen. That’s a community matter that should be debated. Where is the forum for debating it?”

The fact there have been so few parliamentary sittings and no debate by MPs erodes public trust, he says. “I think it creates the most dangerous precedent. I am alarmed that in Victoria there have been relatively no protests about what has happened.”

In Australia, there have been comparatively few voices questioning the pandemic response and even fewer legal challenges.

In contrast, in Germany there have been several court actions. Its constitution contains stronger protections for human rights than Australia’s Constitution.

In July, a court in western Germany overturned a lockdown in the town of Guetersloh, imposed to contain a major outbreak at a meatworks. It found that the measure was “disproportionate”. An earlier legal challenge had been rejected, but when the week-long lockdown in Guetersloh was extended for another week, a second challenge was launched and the court changed its mind — finding that authorities had had time to impose more targeted restrictions.

In Australia, mining magnate Clive Palmer has launched a High Court challenge to Western Australia’s border closure.

One of the few protections provided by our Constitution, relevant to this context, is that trade and commerce among the states and movement across state borders should be “absolutely free” (section 92).

The High Court previously has recognised this right can be restricted by laws that are reasonably necessary to achieve a legitimate end, such as protecting public health. The Federal Court, determining the key facts in Palmer’s case, this week found that the WA border closure was more effective in preventing the spread of COVID-19 than any other measure. This finding — which arguably has made Palmer’s task harder — will be relevant to the High Court’s deliberation on whether the laws are reasonably necessary and aimed at a legitimate end. The case is complicated by the fact the virus numbers keep changing.

Ironically, Victoria is the only state with a human rights charter. (The ACT and Queensland also have human rights acts.)

Speed says the Victorian Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities requires that any restriction on rights must be reasonable and justified.

“There is no point in having a charter if it can be bypassed at the whim of the government,” he says.

He says the real question for Victorian MPs is whether the state of emergency should be extended at all, not whether it should be extended by one or two months or six. “The first critical question is, has the government established that any extension is justified?” he says. “That is not simply what I say but what the Victorian Charter of Rights requires.”

Federal Liberal senator Sarah Henderson points out that under section 204 of the Public Health and Wellbeing Act anyone can seek compensation for losses caused by an improper use of emergency powers. She told parliament on Tuesday this was a “powerful remedy” that gave “every Victorian who suffered loss the right to hold the Chief Health Officer to account”, pointing to Jim’s Mowing, which had vowed to seek compensation for its franchisees and contractors caused by arbitrary rules that allowed council gardeners to work but not private gardeners.

Lockdown lawsuits

Two Melbourne legal centres — Flemington & Kensington Community Legal Centre and Inner Melbourne Community Legal — are examining whether there are grounds for pursuing legal action over the hard lockdown in public housing. Hundreds of police were deployed to contain about 3000 residents in Flemington and North Melbourne for at least five days. This caused extreme trauma for some residents who had already lived through war and persecution overseas.

Flemington & Kensington Legal Centre chief executive Anthony Kelly says policing during the pandemic has been “problematic”. He says some community groups have been targeted disproportionately to the outbreaks they have experienced and says Victoria Police has refused to release data to enable independent bodies to examine this.

Victoria Police also has refused to tell The Australian exactly how many times it has entered premises without a warrant since March. It says it has done so in a “small number of cases” with “authorised officers” appointed by Sutton. Under the state of disaster declared on August 2, police can enter homes without an authorised officer, but these powers have not yet been used, according to a spokeswoman.

Kelly wants more scrutiny of police to occur. “We’ve been calling upon all of the states’ various independent oversight bodies to have more of a role in monitoring policing during the COVID pandemic,” he says. “Some are more receptive than others.”

In Victoria, he says the Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission has been overseeing COVID policing. “We’d like them to be doing much more hands-on investigative work,” Kelly says.

University of NSW professor of law Rosalind Dixon says international law requires that any limitations on rights are necessary, proportionate and subject to continual review. “It’s incredibly important for us to see why this is necessary because it’s to protect the community,” Dixon says.

“For it to be appropriate and legal in international law, and to avoid a dangerous precedent, there has to be continued oversight and justification. What that means is, one, the Premier has to stand up daily and defend the measures based on evidence.

“Second, they have to justify why lesser measures aren’t effective; and third, they have to commit to continually reviewing the measures based on the evidence.”

As much health advice should be released as possible to justify the decisions that have been made, and the courts and parliaments also need to remain in operation to provide oversight, Dixon says. “Courts have adapted in a really impressive way and I think parliament should also adapt,” she says.

Parliament sacrificed

Saunders says it is a concern that parliaments have not met a lot during the crisis, although it has been understandable. Since mid-March, federal parliament will have sat for a total of 16 days by the end of this week — 13 fewer than it was supposed to. In Victoria, both houses have sat for 10 days, as opposed to the 19 scheduled.

A fallback is needed if MPs cannot meet physically, Saunders says. Changes were made last week to enable federal MPs to participate in debate remotely but not to vote. “There is nothing like having them face each other across the chamber,” Saunders says. “Facing each other across Zoom … (or) with a smaller number of people is not the same thing. So I’m not suggesting it as a replacement, but I do think we need to work out how these things can be done without sacrificing parliament.”

On the other side of the spectrum is Sydney property developer Robert Magid, publisher of the Australian Jewish News, who brushes aside slippery-slope arguments. He was born in China under Japanese rule and fled when the Communist Party took over.

He says he can’t think of any previous Australian government that would have abused its emergency powers and says he does not believe this is a serious future risk because of the exceptional strength of Australia’s democracy.

“I can’t imagine a serious abuse of power occurring in Australia,” he says.

No matter where people sit on the spectrum, no one wants governments to be denied the tools they legitimately need to continue the coronavirus fight.

But at the same time there’s no need to hand over a sledgehammer when a nutcracker will do or make it any easier for future leaders to wield those tools for less noble reasons.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout