Cops at odds over deadly Kumanjayi Walker shooting

By the time members of Constable Zachary Rolfe’s team found Kumanjayi Walker, two of them had been hunting him for days.

By the time members of Constable Zachary Rolfe’s immediate response team found Kumanjayi Walker in the remote community of Yuendumu, two of them had been hunting the Aboriginal teenager for several days. A third IRT officer had just returned from his honeymoon, and a fourth had been called back from leave.

All had seen body-worn video footage of the troubled youngster threatening police colleagues with an axe. Each had independently concluded, three of the four told Alice Springs Local Court this week, that Walker was dangerous and the axe incident just days prior could have been fatal for anyone involved.

When police received information Walker might be at Warlpiri Camp in Alice Springs, officers waited until an entire patrol group of six constables and a sergeant had assembled — “so seven police officers to affect the arrest of one man”, the court heard.

But by the time the IRT squad and a dog handler stumbled upon Walker on Saturday, November 9 last year, they were going house to house at dusk in poorly defined pairs, with no designated leader and no agreed plan about what to do if Walker appeared.

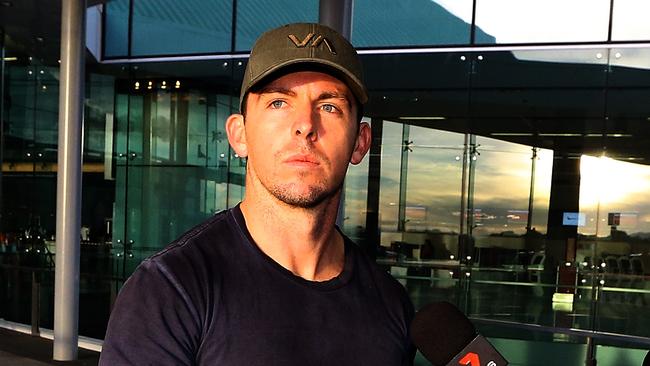

During three days of evidence at Constable Rolfe’s committal hearing — the decorated young officer and army veteran has been charged with and intends to plead not guilty to Walker’s murder — the court heard there was confusion about the group’s mission.

All five men had been sent an operational plan prepared by Yuendumu’s officer in charge, Sergeant Julie Frost. She told the hearing it asked them to concentrate on “high-visibility policing” (driving around) and give local officers a good night’s sleep.

“We had had a spate of unlawful entries in the community and also a number of riots in the community, and also there had been a funeral,” Sergeant Frost said. “I wanted them to conduct high-visibility policing throughout the community and where the nurses’ houses were, which had continually gotten broken into.”

Her arrest plan for Walker involved sending IRT members with a local officer called Felix Alefaio to try to pick him up at 5.30am the next day when he would be asleep. “I particularly wanted Felix to be present during the arrest … because Felix knows him very well,” Sergeant Frost said. “I said specifically … we want the dog to be utilised … we know he (Walker) will run.”

Experts praised Sergeant Frost’s strategy as a sensible means of minimising risk. But the three IRT witnesses denied receiving her email and contradicted her evidence about handing the group a printed version and briefing them personally.

Dog handler Adam Donaldson agreed he did receive the email and Sergeant Frost’s briefing. IRT member James Kirstenfeldt recalled seeing “some other email” about an early morning arrest but not the one shown to him at the hearing.

IRT members Anthony Hawkings and Adam Eberl said they did not or could not recall receiving Sergeant Frost’s briefing about their mission and her arrest strategy, and thought their sole goal was to get Walker.

The group headed out immediately on the evening of November 9 in search of him but gave differing accounts at this week’s hearing about whether they intended to arrest him immediately or merely gather intelligence.

When Constable Rolfe and Sergeant Eberl came upon Walker in a darkened room, he gave a false name, and the pair had difficulty recognising him. Walker began to struggle moments later, according to body-worn video footage played to the court.

Within 10 seconds, Walker had stabbed Constable Rolfe in the shoulder and been allegedly shot by him once in what experts deemed was a justifiable use of force. But by the time Constable Rolfe allegedly fired again less than three seconds later, Sergeant Eberl had pinned Walker to the floor. Those two shots, at nearly point-blank range and into Walker’s chest, were deemed unwarranted by experts.

Constable Rolfe’s lawyers will return later this month to argue he has no case to answer.