Closure for Montevideo Maru victims’ families – and lesson for Australia’s defence

Montevideo Maru’s discovery closes a painful chapter in Australian history.

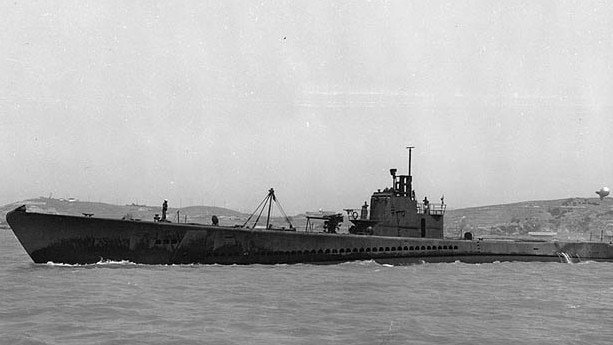

Through the long tropical night the USS Sturgeon carefully shadowed its prey, as it tracked into the deep waters of the South China Sea.

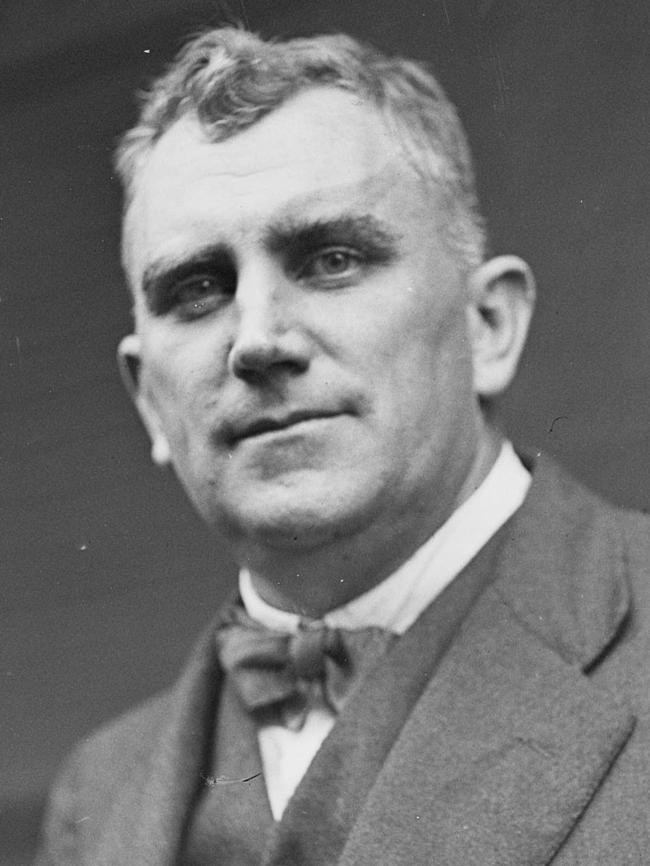

Three weeks earlier, the American submarine commanded by Lieutenant Commander William “Bull” Wright had sailed from Fremantle after a brief refit to hunt Japanese shipping off the northwest coast of The Philippines’ island of Luzon. During WWII, Fremantle quickly became the largest submarine base in the southern hemisphere, playing host to more than 170 submarines from the US, UK and Dutch navies.

Soon after 10pm on June 30, 1942, the Sturgeon had spotted a darkened ship north of Cape Bojeador coming out of the Babuyan Channel making at top speed towards Hainan Island.

“Put on all engines and worked up to full power, proceeding westward in an attempt to get ahead of him. For an hour and a half we couldn’t make a nickel. This fellow was really going, making at least 17 knots and probably a bit more as he appeared to be zigzagging,” Wright later recorded in his patrol report.

After midnight, the unmarked Japanese merchant ship finally slowed, allowing the Sturgeon to eventually get ahead and dive. At 2.25am on July 1, at periscope depth, the Sturgeon fired four torpedoes from 4000 yards, striking the unmarked vessel aft of the funnel. “At 2.40 observed ship sink stern first. He was a big one,” the patrol report noted.

In just 11 minutes, the American submarine had sent the MV Montevideo Maru, a 7200 tonne Japanese passenger line, requisitioned as an Imperial Japanese Navy transport, to the bottom.

Wright and his 50-strong crew had no idea that incarcerated on board the Japanese vessel were 1060 prisoners of war – 845 military personnel and 209 civilians. The sinking of the Montevideo Maru remains the largest single loss of life at sea in Australian history.

With war in the Pacific on the horizon, Australia’s military commanders in early 1941 dispatched a token 1400-strong army contingent, known as Lark Force, to defend Rabaul, the administrative capital of the Australian Territory of New Guinea.

They included the 2/22 Battalion, raised mainly in Victoria, anti-tank and artillery detachments, army engineers and personnel from the 2/10 Field Ambulance, together with six army nurses.

As part of the fledgling force, 250 men of the 1st Independent Company, a commando unit, were sent to guard Kavieng on neighbouring New Ireland and adjacent islands. In December 1941, four Hudson bombers together with 10 obsolete Wirraway fighters from the RAAF’s 24 Squadron were also dispatched to Rabaul – a decision described by leading RAAF historian Alan Stephens as “an act of delinquency”.

The manifestly ill-equipped military forces deployed to Rabaul exemplified a monumental strategic failure by the Australian government and its military planners to appreciate the scale and nature of total war as practised by Japan.

Lark Force was no match for a massive Japanese invasion fleet, including 5000 marines, which swept down on New Britain on January 23, 1942. Three weeks earlier, Rabaul, surrounded by volcanoes and situated on the north eastern tip of the picturesque Gazelle Peninsula on the island of New Britain, had become the first Australian territory to be bombed during WWII.

In the weeks running up to the invasion, Canberra dithered about evacuating the civilian administration and finally did nothing. In secret diplomatic cables, the government acknowledged that, in the event of conflict, the tiny army garrison at Rabaul was highly vulnerable and likely to be “hostages to fortune”. Rabaul and its surrounding settlements were quickly overrun by Japanese forces, who acted with great brutality towards Australian servicemen and civilians alike.

In February, an estimated 160 escaping Australians were massacred at Tol Plantation on the coast due south of Rabaul. In the end, only around 400 members of Lark Force and a handful of civilians managed to get away, walking vast distances across mountainous jungle terrain before being making the hazardous sea passage in small craft to the New Guinea mainland. Those who were not killed in the initial weeks of the Japanese invasion eventually surrendered and became prisoners of war.

Summing up the debacle at Rabaul, Paul Hasluck, author of two fine volumes of Australia’s Official WWII History, concluded: “In February and March 1942 those who died and those fugitives who struggled desperately and hazardously to rejoin their own countrymen, creeping along the sea coast by night, toiling up mountains, and through the jungle, had a double loneliness, remote from physical aid and protection and remote from the concern of their fellow countrymen. To them belongs the tribute due to those who suffered and those who dared, but to the Australian government the blame for ignorance, ineptitude, and neglect of responsibility.”

Early in the morning of June 22, 1942, the Australian POWs held at Rabaul (excluding 60 commissioned officers and the army nurses, who remained behind and later were transported to Japan) were marched down to the wharf on Rabaul harbour and embarked on the Montevideo Maru. The Japanese vessel then sailed unescorted, bound for Hainan Island. Australians were not to learn the fate of their countrymen until late 1945, when an Australian army investigating officer in occupied Japan, Major H.S. Williams, was given a Japanese government casualty list of the Australians who had been taken on to the ship.

The POWs on board the Montevideo Maru came from all over Australia and all walks of life.

They included Harold Page, a decorated WWI veteran and deputy administrator of Australian New Guinea. Page’s brother was former prime minister Earle Page. Twenty-year old Kenelm Mackenzie Ramsay, from Quirindi, NSW, was a star Wallaby forward and commando with the 1st Independent Company. Salvation Army bandmaster and well-known music composer Arthur Gullidge from Broken Hill and his bandsmen formed the nucleus of the 2/22 Battalion band. Sixteen of the mainly Melbourne-based Salvos were to perish on the Montevideo Maru.

Seven Methodist missionaries based at Rabaul were lost, including Sydney Beazley, uncle of former Labor leader, Kim Beazley. Three brothers from Sydney, Dudley, Daryl and Sidney Turner, serving with the 1st Independent Company all perished on the Montevideo Maru together with 129 other men from their 250-strong commando unit.

In the 80 years since, the tragedy of the Montevideo Maru has continued to haunt the lives of thousands of Australians whose relatives were aboard the doomed ship. From 1942, grieving families searched desperately for any clues about the fate of the missing and for financial compensation from a seemingly callous and uncaring government. Descendants have continued to campaign for a fitting remembrance of the military and civilian personnel who went down on the Montevideo Maru.

Ever since the 1950s, there have been calls for an official search to be conducted to find the missing ship. It was not until July 2012 – 70 years after the sinking – that a permanent memorial was finally unveiled by then governor-general Quentin Bryce at the Australian War Memorial.

Last Tuesday, around 4pm AEST, after almost three weeks at sea, the deep ocean survey vessel Fugro Equator located the wreck of the Montevideo Maru 4200m down on the flat seabed of the South China Sea. More than three years in the planning, the search expedition was led by Sydney-based Silentworld Foundation, a not-for-profit organisation promoting maritime archaeology founded and led by prominent Sydney businessman and philanthropist John Mullen. Silentworld, assisted by the Defence Department, teamed up with leading Dutch geospatial survey company, Fugro.

In December 2017, the team had successfully located the whereabouts of Australia’s first WWI submarine, the AE1, which sank with the loss of all hands in September 1914 off the coast of New Britain, not far from Rabaul.

Working from the co-ordinates originally supplied by the USS Sturgeon in 1942, the multinational team on the Fugro Equator carefully delineated a search area where the Montevideo Maru most likely lay. A hull-mounted sonar started mapping the sea floor, its data programmed into the vessel’s highly sophisticated autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) to enable a far more detailed grid-pattern survey at just 100m above the seabed.

Captain Roger Turner, a former Royal Navy nuclear submarine engineer and the leading marine search specialist on board the Fugro Equator, told The Australian that the “boringly flat and featureless” seabed in the search area had helped continually refine the search box to a final radius of nine nautical miles.

Bad weather hampered the search in the initial days. After analysis of terabytes of data streamed from the AUV, the search team found the Montevideo Maru in two sections – the bow section located 500m north of the stern.

For Andrea Williams, who chairs the Rabaul-Montevideo Maru Society (now part of the Papua New Guinea Association of Australia), the discovery stirred deep emotions. For years Williams has worked tirelessly to ensure the tragedy of the Montevideo Maru remained firmly etched in Australia’s national consciousness.

Speaking to The Australian from the Fugro Equator yesterday, Williams said it had been hugely rewarding to be part of the search team. “I have been brought up with this story having had a grandfather on the Montevideo Maru and spent a lot of time looking for answers,” she said, adding she had seen many families suffer from not really knowing what happened to their relatives.

“This is very special and going to be very comforting to relatives. It will help give the Montevideo Maru its rightful place in Australian history.”

Australian War Memorial chairman Kim Beazley said the finding the Montevideo Maru represented “a substantial enhancement of the character of our historical memory”. “I suspect my family is much like everyone else’s connected to the casualties of our greatest marine disaster,” he said. “How those whose family members lived with the prospect of getting clarity at war’s end on the fate of their relatives is very much part of our family lore.”

Late Saturday, the searchers and crew on board the Fugro Equator held their own simple commemoration at the approximate site where the Montevideo Maru went down. Floral wreaths were cast on to the azure sea together with “sembazuru” or Japanese paper cranes as a final tribute to all those, including the Japanese crew and guards who died on the Montevideo Maru.

In early 1942, Australia faced the most serious test in its short history as Japanese forces descended with frightening speed into the South Pacific. The early months of the conflict, including the loss of Rabaul and the tragedy of the Montevideo Maru, underlined the manifest strategic policy failures of the Australian government. At sea, in the air and on land, our military forces, however courageous, were no match in the face of a formidable and far better equipped foe.

On the eve of Anzac Day and the launch of a fresh defence strategic review, the brutal experiences of early 1942 should be remembered. Australians expect that we should be able to defend ourselves. This starts with a clear recognition of our unique strategic geography as an island continent and an acceptance of the fundamental importance of a coherent maritime strategy for national defence.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout