Climate scientists lost on extent of rising seas

Major uncertainties remain on how much melting ice, particularly in Antarctica, will lift sea levels over coming centuries.

Major uncertainties still remain on how much melting ice, particularly in Antarctica, will lift sea levels over coming centuries.

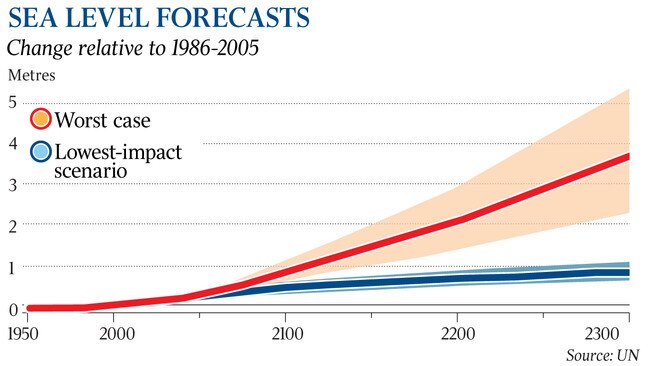

The worst-case scenario for sea-level increases by 2100 has been lifted to between 60cm and 110cm if greenhouse gas emissions continue to increase strongly.

The best case in a new report prepared for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is for sea levels to rise between 30cm and 60cm by 2100 if greenhouse gas emissions are sharply reduced and global warming limited to less than 2C.

The IPCC report says the rate of sea-level increases has accelerated in recent decades due to melting ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica, as well as meltwater from glaciers and the expansion of warmer seawaters.

IPCC working group co-chair Valerie Masson-Delmotte said the range of sea-level projections for 2100 and beyond “is related to how ice sheets will react to warming, especially in Antarctica, with major uncertainties still remaining”.

Debra Roberts, co-chair of the IPCC working group that prepared the report, said drastic action was needed to limit sea-level rises that would impact millions of people around the world.

The report said once-in-a-century extreme coastal flooding could be expected at least once every year by the middle of this century. “We will only be able to keep global warming to well below 2C above pre-industrial levels if we effect unprecedented transitions in all aspects of society, including energy, land and ecosystems, urban and infrastructure, as well as industry,” Dr Roberts said.

Earlier IPCC reports have called for the phase-out of fossil fuels and a change to diets away from meat.

The special report on oceans and the cryosphere is one of a series commissioned by the IPCC. Others were on the impact of 1.5C warming, the land sector and biodiversity.

The global ocean covers 71 per cent of the Earth’s surface and contains about 97 per cent of the Earth’s water.

The cryosphere refers to frozen components of the Earth’s system, which cover about 10 per cent of Earth’s land area.

Most of the findings in the latest report are already well known and include the impact of warmer temperatures on coral reefs and rising sea levels on coastal development. The report says that, over the 21st century, the ocean is projected to transition to unprecedented conditions, with increased temperatures, greater upper-ocean stratification and further acidification. Marine heatwaves and extreme El Nino and La Nina events are projected to become more frequent.

Global-scale glacier mass loss, permafrost thaw, and decline in snow cover and Arctic sea ice extent are projected to continue in the near term (2031-50).

The Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets are projected to lose mass at an increasing rate throughout the 21st century and beyond. “One new thing is that we can now say with some confidence that Arctic sea-ice decline is unprecedented in at least 1000 years, which is some of the clearest evidence yet that human impacts on climate already dominate over anything natural,” said professor Steven Sherwood from the University of NSW.

“Also, this report examines expected changes out to … 2300, when sea-level rise is projected to be three metres to four metres without mitigation efforts, but could be kept under one metre with strong mitigation efforts.”

Report co-lead author Nerilie Abram, from the Australian National University, said by reducing greenhouse gas emissions the nation could gain more than a decade to prepare parts of the coastal infrastructure against damaging events.

“But even if we act now, some changes are already locked in and our ocean and frozen regions will continue to change for decades to centuries to come, so we need to also make plans to adapt,” Professor Abram said. She said there were a range of possible options, from building barriers to planned relocation, to protecting the coral reefs and mangroves that provide natural coastal defences.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout