Chinese social media censor Jasmine Sun poisoning posts

Users have been banned over posts containing ‘illegal content’ after The Australian revealed the woman alleged to be at the centre of the poisoning of Zhu Ling is living in Port Stephens.

Chinese social media networks have scrambled to censor posts about a property investor living in Australia accused of being at the centre of a mysterious and deadly poisoning that has enthralled millions in China for 30 years.

Popular social media websites such as Weibo have banned users for making posts containing “illegal content” after The Australian revealed on Friday the woman alleged to be at the centre of the poisoning – and subsequent recent death – of Chinese university student Zhu Ling in the mid-1990s, is living in Port Stephens.

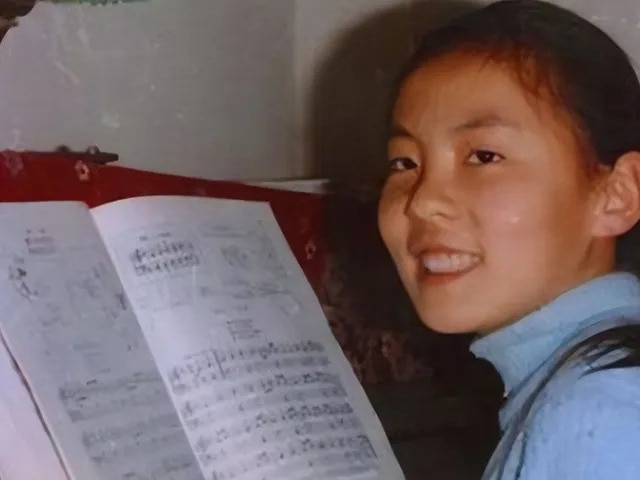

On Friday The Australian revealed campaigners identified Shiyan Sun as Sun Wei, the woman accused of poisoning Zhu after allegedly becoming jealous of her university roommate’s talent, popularity and love life.

In the 24 hours since this masthead’s story was published, posts have been censored in a bid to stall the public campaign to bring Ms Sun back to China, with one expert saying social media providers are fearful of being shut down by the Chinese Communist Party if they allow large public campaigns to blow up online.

Social media users have also reported posts achieving far fewer likes and reach, receiving just a handful when they would normally receive thousands.

They claim Ms Sun has changed her name, and even her birthday, to shed her previous life as Sun Wei, who was studying chemistry at the university and is believed to have had access to thallium, the highly toxic metal used in the poisoning.

Photographs of Ms Sun and her husband – the first time she had been seen in 20 years – went viral before quickly being removed, with social media websites fearful they will be shutdown.

The platforms include Xiaohongshu, the heavily censored version of China’s Instagram platform, which has been banning posts and users who publish Ms Sun’s name.

Chinese “netizens”, however, have been attempting to bypass the censorship by using the Chinese-language symbol for a jasmine flower in reference to the notorious case.

Tzung-Li Tang, a Chinese-English interpreter and lecturer, is a member of volunteer team Justice for Zhu Ling, which has pushed for Ms Sun’s extradition, and claims she has not seen censorship of the case on this scale before.

“I don’t think censorship of Zhu’s case has happened this frequently before,” Ms Tang said on Friday. “There was censorship, but not nearly as much as now.”

But Paul Monk, former head of the China desk in the Australian government’s Defence Intelligence Organisation, said the CCP has always censored any story, civil or political or international that was deemed adverse to its interests. “Famously, of course, if there’s any natural disaster or human error that caused disaster, including (the) outbreak of Covid, it censors all of that and tries to control the narrative and people who try and testify to the truth,” he said.

James Griffiths, journalist and author of The Great Firewall of China, said censorship wasn’t always consistent or self-explanatory in China.

“The response to this case is very reminiscent of an earlier period in the Chinese internet where you had what was euphemistically called human flesh searches, which was basically doxxing around criminal cases and controversies online sometimes involving allegedly corrupt officials,” he said. “I think there may be a level of discomfort potentially with the censors.”

Griffiths said the privatisation of censorship, which makes social media companies in China responsible for censorship to avoid being shut down, was one of the most effective features of China’s “great firewall”.

Social media campaigns are urging Anthony Albanese, Immigration Minister Andrew Giles and Foreign Minister Penny Wong to deport Ms Sun to China to face questions over the Zhu poisoning.

“There is always concern on the Chinese internet and from Chinese internet censors about mass action. It doesn’t matter what people are organising around,” Griffiths said.

“You could see the logic and thinking that, well, if we show this mass movement of people complaining about a criminal case that was potentially mishandled, what precedent does that set for the public deciding they should have a say in how these things are approached, or have a say in how historical grievances are addressed? That is not a desirable outcome.”