China’s wolf warrior slinks away, bloodied but unbowed

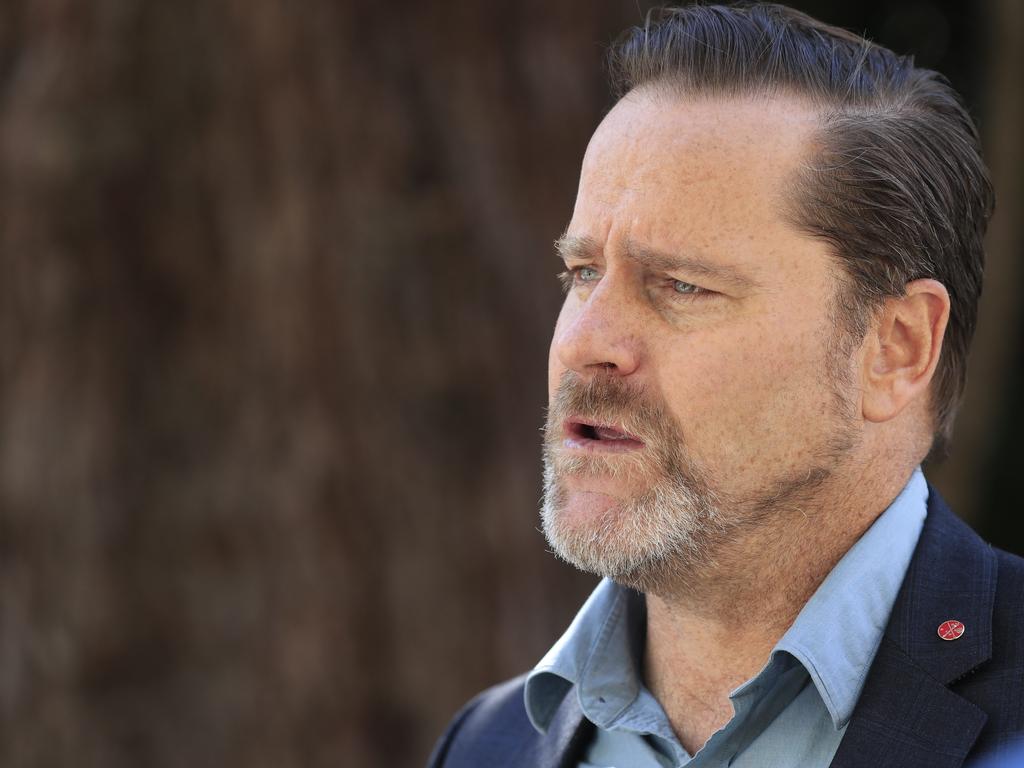

After baring his fangs for so long, Chinese ambassador Cheng Jingye leaves a legacy that will never be forgotten in Australian diplomacy.

After baring his fangs at Australia for so long, China’s self-styled wolf warrior is leaving Canberra with barely a whimper.

Ambassador Cheng Jingye hadn’t completely run out of friends after his tumultuous five year posting in Canberra but it’s fair to say they were thin on the ground.

Perhaps that is why Mr Cheng didn’t bother to call his old sparring partner, Foreign Minister Marise Payne, to tell her he was returning to Beijing.

Mr Cheng also didn’t bother holding a farewell party for Canberra’s diplomatic community, most of whom found out about his imminent departure via a text from the dean of the diplomatic corps. It is understood that China has put forward a name to Canberra to replace Mr Cheng.

In a statement published on its Canberra embassy website overnight, Mr Cheng deplored “difficult” bilateral relations and rejected media reports on his quiet exit, claiming that he had “bid farewell to people from all walks of life in Australia … through meetings, phone calls and correspondence” before wrapping up his tenure.

“The current difficult situation facing China-Australia relations is saddening,” he said.

“It is hoped that the Australian side will work in the same direction with the Chinese side, on the basis of mutual respect, equality and mutual benefit, to overcome the difficulties and make joint efforts to push the bilateral relations back to the right track as soon as possible,” the statement read.

While Mr Cheng is exiting quietly, he leaves behind a legacy that will never be forgotten in Australian diplomacy. The 62-year-old turned Australia-China relations into a blood sport, eagerly adopting the call of China’s President Xi Jinping for his envoys to show more “fighting spirit” to defend Beijing’s interests around the world.

With Beijing’s backing, Mr Cheng abandoned the pretence of diplomatic niceties to instead hector and threaten Australia on any manner of alleged sins from foreign interference to Huawei to the coronavirus pandemic to Taiwan and human rights.

With each perceived new slight against China by Australia, Mr Cheng would bare his fangs ever more, threatening to withhold tourists and Chinese students, and even stop Chinese from buying our beef and wine in the hope that Canberra would back down.

His mantra was that China was not beating up on Australia, rather it was Australia that was recklessly setting fire to the relationship with its largest trading partner. “It seems that being tough on China or even attacking China has become a politically correct thing to do. What is more astonishing is that some Australians claim that such provocations and confrontation are ways to safeguard Australia’s values, national interest or security,” he said earlier this year.

Yet when Mr Cheng arrived in Canberra in 2016, he was not a natural wolf warrior, the term used to describe China’s new breed of in-your-face diplomats.

Mr Cheng, whose glasses and thinning hair made him look more like a mild-mannered office worker than a gladiator, had spent much of his career working on multilateralism in New York, Geneva and Vienna.

His arrival in Australia coincided with a growing wariness here about the less savoury aspects of our largest trading partner.

The proliferation of Chinese spies and growing efforts to interfere in Australia’s political system led to the passing in 2018 of foreign interference laws that were indirectly targeted against Beijing.

Mr Cheng described the laws as unfair and irrational. Worse was to come in early 2020 when Australia banned China’s telecommunications giant Huawei from helping build the nation’s 5G network for fear the Chinese would use Huawei to spy on Australians.

Mr Cheng slammed the decision as being “politically motivated”. “It is a discrimination against the Chinese company. At the same time it doesn’t serve the best interest of the Australian companies and consumers,” he said.

It was Australia’s call last year for an independent inquiry into the origins of the coronavirus pandemic that sent China — and Mr Cheng — into the greatest rage.

Mr Cheng said China was “dismayed” by the call for an inquiry, which he claimed was dangerous and politically motivated and made at the request of the Trump administration. He said tourists and Chinese students would question coming to Australia and China might even stop consuming Australian beef and wine.

“The Chinese public is frustrated, dismayed and disappointed with what Australia is doing,” he said. “I think in the long term ... if the mood is going from bad to worse, people would think ‘Why should we go to such a country that is not so friendly to China?’ The tourists may have second thoughts. The parents of the students would also think whether this place which they found is not so friendly, even hostile, or whether this is the best place to send their kids.”

Then in words that would once have seemed unthinkable from a diplomat, he added: “It is up to the people to decide. Maybe the ordinary people will say ‘Why should we drink Australian wine? Eat Australian beef?’ ” he said.

That was a step too far for Senator Payne, who hit back, defending the call for an inquiry and criticising the ambassador.

“A transparent, honest assessment of events will be critical as we emerge from the pandemic and learn important lessons to improve our response in the future,” she said.

“We reject any suggestion economic coercion is an appropriate response to a call for such an assessment when what we need is global co-operation.”

China then slapped more than $20bn in trade bans on Australian exports, including beef, barley, lobsters, coal, copper and wood.

Late last year, Mr Cheng stepped up his provocations by orchestrating the leak to the media of a dossier of 14 grievances China had with Australia’s China policy.

These included academic visa cancellations; “spearheading a crusade” in multilateral forums on China’s affairs in Taiwan, Hong Kong and Xinjiang; calling for an independent investigation into the origins of Covid-19; and banning Huawei. China said if Australia backed away from policies on the list, it “would be conducive to a better atmosphere”.

In April, Mr Cheng held a two-hour press conference to rebut growing human rights criticism of China’s repressive treatment of Muslim minorities. In a media event called “Xinjiang is a Wonderful Land”, Mr Cheng sought to undermine independent reporting of repression, forced labour and sterilisation of Muslims in China’s northern region.

“Any people, any country, should not have any illusion that China would swallow the bitter pill of interfering or meddling in its internal affairs trying to put so-called pressure on China,” he said. “We will not provoke but if we are provoked, we will respond in kind.”

By this year, Mr Cheng was an increasingly isolated figure in diplomatic circles in Canberra.

Despite his threats, which were backed up by Beijing, neither the Morrison nor Turnbull governments took a backward step on the China policies that he attacked.

If anything, Australia has continued to distance itself from Beijing with the recent AUKUS nuclear submarine agreement and its growing participation in the so-called Quad — the informal grouping of Australia, the US, India and Japan.

Mr Cheng leaves Canberra with Australia-China relations at their lowest ebb in a generation, a far cry from his hopes when he arrived. “Our relations today have never been broader or deeper, and have maintained a sound growth momentum,” he said in a 2016 message still posted on his embassy’s website.

“With the joint efforts of Chinese and Australians across the sectors, I have every confidence in the future of this relationship.”

Instead, the wolf is departing Canberra with little to show for his warrior diplomacy, leaving a long road ahead for the China-Australia relationship.

With Heidi Han

More Coverage

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout