Captain James Cook’s Endeavour can finally lay at rest

The Australian National Maritime Museum says the Endeavour has unequivocally been identified in Newport Harbour, Rhode Island. But not everyone is as confident.

Oak trees grow slowly in the cool, rain-shadowed Vale of York, inland from the North Yorkshire coast. The strong, gnarly old wood was favoured by the boat builders of Whitby who made the robust whaling vessels that sailed to Greenland and back.

And that will be why enough of what became the HM Bark Endeavour – the ship Captain James Cook sailed so far on voyages that changed our world – survives and can be positively identified as his vessel.

“I am satisfied that this is the final resting place of one of the most important and contentious vessels in Australia’s maritime history,” said Kevin Sumption, director of the Australian National Maritime Museum, announcing on Thursday that, after 22 years’ research, the Endeavour had unequivocally been identified among the remains of wrecks scuttled on August 4, 1778, in Newport Harbour, Rhode Island.

But not everyone is as confident. The Rhode Island Marine Archaeology Project, which has led the search for the Endeavour, considers the Australian announcement to be rash and “a breach of contract”.

Following Sumption’s victorious announcement as he stood alongside Arts Minister Paul Fletcher, RIMAP executive director Kathy Abbass took a shot across their bows: “What we see on the shipwreck site under study is consistent of what might be the Endeavour, but there has been no indisputable data to prove the site is that iconic vessel, and there are many unanswered questions.”

She said her organisation’s decisions about the provenance of the remains “will be driven by proper scientific process and not Australian emotions or politics”.

A confident Fletcher had no such hesitation: “As the positive identification of the Endeavour shows, marine archaeology is a fascinating and rapidly developing field of expertise.”

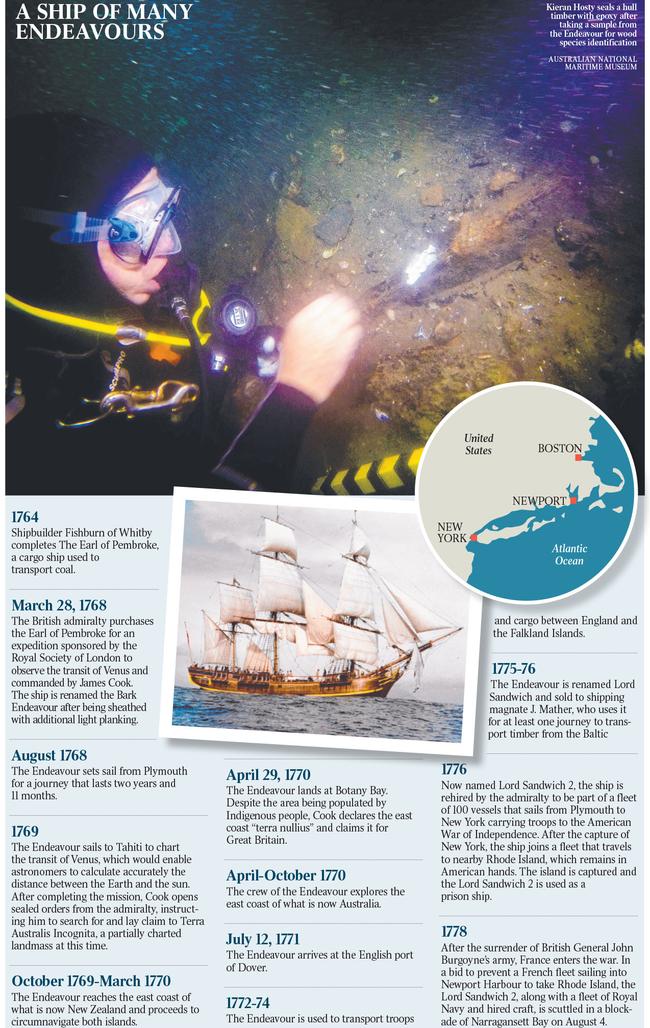

The story of the latter years of Cook’s famous ship was unravelled in 1997 when it was linked to a troop carrier used by Britain to bolster manpower during the American Revolutionary War. It turns out Endeavour, after Cook’s first voyage, had been renamed Lord Sandwich, moving supplies and soldiers during several runs to the Falkland Islands before returning to work as a collier, and finally joining the fleet that shipped troops to strengthen the British forces on America’s east coast.

Aboard the Lord Sandwich were soldiers knows a Hessians, German troops hired out to the English for the occasion and legendary for their discipline.

Once the Endeavour-Sandwich connection was confirmed, the focus swung to the wrecks off Rhode Island. A dozen vessels were scuttled along with the Lord Sandwich, joining perhaps another 220 wrecks in that bay.

Abbass and her team set out in 1993 to try to identify those connected to the Revolutionary War. She wasn’t looking for the Endeavour, few Americans know of it, and in any case no ship of that name lay there. Navy ships then, like cruise liners today, were bought and sold, remodelled, repaired, and repurposed. With international registers it is simple to trace the pedigree of today’s shipping. The heritage of ships of Cook’s era easily slips away and is often hard even to guess at.

But with the possibility that one of the 13 wrecks might be Endeavour, Abbass’s group, assisted by Sumption’s ANMM team, spent 16 years diving on them during the summer’s weather window, not that it much changed the dark, cold, silty seabed world.

Historical records suggested where the ships were probably holed and sunk. That ruled out five of the 13, and with the oddly fat Endeavour – 30m long and 8.8m wide, perfect for carrying coal – unlike most other wrecks its durable Yorkshire oak was likely to stick out. In 1999, confidence that they might be on to the Endeavour was growing. Abbass told Australian Geographic back then: “We are coming closer to saying we’ve found it, but we still have to prove it.”

The rapid development of what is known as photogrammetry was helping. The seabed on which these sunken ships lie is featureless to the untrained eye, and even for experts there are no overt clues to which wreck is which, or even their orientation on the sea floor. But by taking photographs of the sites from various angles, scientists are able to render 3D images revealing them in greater detail.

Those technologies and two decades of research appear to have confirmed the Endeavour has been found. And Sumption was keen to credit who got us this far: “We must pay great tribute to the incredible work of (Abbass and) her team at the maritime archaeology project … without Kathy’s work, we would not be standing here today.”

Not only was Endeavour home to Cook for three years as he mapped our east coast and circumnavigated New Zealand’s north and south islands, but he proved the boffins of the Royal Society right: there was a Great South Land, and it had now been claimed for Britain.

Sumption noted on Thursday that Endeavour had “played a critical role not only in the history of the United Kingdom, but also New Zealand, of course Australia, and now the United States”.

But its long journey across uncharted oceans proved something else – that the navy had a good eye for the ship that would change the world.

When they saw the Earl of Pembroke docked and for sale at Whitby, it looked like a very strong box with a minimal draft. It would be perfect for shallow waters, would stay upright if grounded, but would be relatively easy to manoeuvre off obstacles. All of which Cook confirmed when he hit coral at what we know as Endeavour Reef off Cooktown.

John Longley might know more about the Endeavour than anyone. He is a councillor at the ANMM, was one of the crew aboard Australia II, was part of the history-making America’s Cup-winning team of 1983, and oversaw the six-year build of the faithful replica Endeavour that sits in Sydney’s Darling Harbour.

“I built that ship from the keel up,” he said. “It is exactly the same as the original.”

The replica was constructed guided by comprehensive measurements and drawings made at Deptford in London when Endeavour was in dry dock being prepared for Cook.

“Every time I see a photograph of some part of (the Rhode Island wreck), I think ‘I built that!’ I am certain it’s the Endeavour.”

More Coverage

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout