Budget improvement driven by one-off commodity spikes and surging inflation

Gas and coal profits are driving a revenue boost, which is repairing the fiscal bottom line.

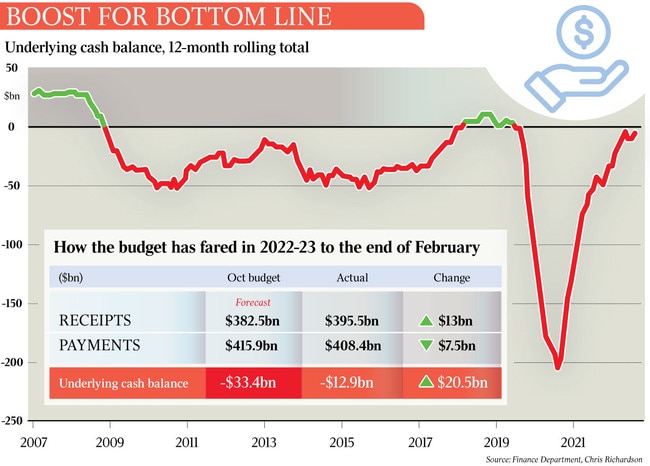

The revenue boost from Ukraine war-driven exorbitant gas and coal prices and persistently high inflation has produced a $20.5bn improvement in the federal budget’s bottom line.

But the tax bonanza may neither last nor be sufficient to pay for the expected increases in Canberra’s spending in coming years, with former Treasury secretary Ken Henry warning a lack of tax reform meant a “fiscal crisis” was on the horizon.

Dr Henry said massive budget deficits made it even harder to execute much-needed reforms as there was less fiscal space to compensate those who stood to lose from tax changes.

Speaking after a tax roundtable in Parliament House hosted by independent MP Allegra Spender, Dr Henry said: “Nothing will happen (on tax reform) without political engagement, and political engagement has been absent for a very long time on tax and on the tax policy front.”

This policy vacuum meant the threat of a fiscal “crisis” – as identified in the first intergenerational report he led two decades earlier – now loomed even larger.

“We’ve got a lot of data now to make an assessment of the extent to which we’ve made progress in averting the crisis that was being called out in that first intergenerational report,” he said.

“Where we find ourselves today is in a worse position, 20 years into the 40-year projections contained in that first intergenerational report.”

Finance Department figures on Friday show that for the first eight months of this financial year, the underlying cash deficit was $12.9bn, compared with the October budget’s profile of $33.4bn.

The result was due to a $13bn rise in revenue, including more tax, GST and interest income, and a $7.5bn fall in spending.

Finance Minister Katy Gallagher said the near-term budget improvements “are a deliberate and direct result of our strategy of relief, repair and restraint”.

“Rather than squander the proceeds of higher commodity prices like our predecessors, we’re banking most of the upward revisions to revenue and showing the necessary spending restraint,” Senator Gallagher said.

Writing on Friday, Jim Chalmers warned that slowing economic growth and volatility in global financial systems had up-ended the government’s strategy ahead of the May 9 budget.

“Our budget’s long-term structural position also remains under pressure from the Big Five of interest costs, NDIS, aged care, health and defence,” the Treasurer wrote in this newspaper.

“And, while elevated commodity prices should provide another near-term boost to revenue, this won’t make up for the medium-term pressures we face.”

In the year to February, the underlying cash deficit was $3.7bn. Budget watcher Chris Richardson said two years ago the matching deficit was $204bn.

“To date, Australia’s slowdown hasn’t been notable,” the Rich Insight principal said.

“And it is showing up less in the budget than it is in the economy.”

Both the boost to income and reduction in debt have changed the debt to gross domestic product ratio in our favour.

Mr Richardson has calculated that Australian federal net debt of $538bn is now likely to be 21.4 per cent of GDP, the same proportion before Covid-19 hit our shores three years ago and elicited a mammoth fiscal response.

Dr Chalmers has said he is pursuing a “staged, methodical approach”, after announcing a planned $2bn hit to tax concessions for individuals with more than $3m in superannuation.

But Dr Henry warned that a piecemeal approach would fall short of what is required.

“I think now’s the time to be asking ourselves the question whether it’s too late to avert the crisis that was spelled out in the first intergenerational report.

“I don’t think it is too late. But I think we do need to recognise that in order to avert the crisis, we need to do things very, very very quickly.”

EY Port Jackson Partners’ John Daley, a former chief executive of the Grattan Institute, said “very few governments have dug themselves out of the structural budget imbalance only by cutting costs or only by increasing taxes”.

Mr Daley said history shows reform comes in packages, where “you can point to losers, but you can also point to winners, and that makes the politics more easy, or at least less difficult”.

Centre for Independent Studies senior fellow Robert Carling agreed that “the best time to do tax reform is when we’re in a position of budgetary strength”.

“You have to have a very long-term focus, because clearly the politics of this situation are such that nothing much is going to happen in the way of broad reform for some time,” Mr Carling told the tax event.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout