Bold visions and cold reality of Antarctic pioneers backed by The Australian

A remarkable, harrowing adventure in the remote wilds of the Antarctic holds a unique and deeply personal place in the foundation history of The Australian newspaper.

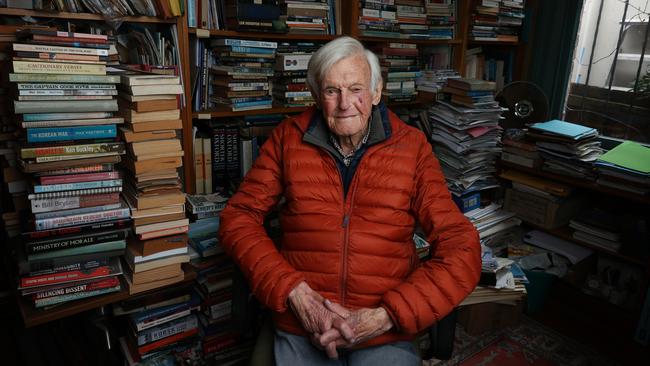

The 1964 expedition most famously associated with Dr Grahame Budd, medical officer and leader of many Antarctic research missions, attached him firmly to the remote Southern Ocean territory of Heard Island – and, more curiously, to the history of this newspaper. For he is one of the rare living links to the early editions of The Australian, which was born the same year Budd’s remarkable journey began in Sydney, and was to a great extent responsible for it.

The young, newly confident nation was ready for adventure, and there was a serendipitous synergy between the bold enterprise of Rupert Murdoch’s vision for a national newspaper and the defiant bravery of the young men who were charting a new path to the forbidding, frozen south.

Heard (named for Captain John Heard of the merchant ship Oriental, who first spotted the island in November 1853) was ceded to Australia by the British in 1947. Big Ben, the giant ice-clad volcano that rises from it, thereupon became, at the stroke of a pen, the country’s highest mountain; at 2745m, it’s half a kilometre higher than Kosciuszko on the mainland. It was still unclimbed in 1964: an irresistible challenge, then, for a youthful explorer.

Budd and two companions, Jon Stephenson and Warwick Deacock, had attempted an ascent of Big Ben in 1963 under the auspices of the Australian Antarctic Division, but failed, almost losing their lives 450m short of the summit.

Remarkably undeterred, Budd and Deacock applied to the Australian National Antarctic Research Expedition to make a second attempt the following year, but ANARE had no funds to spare. So Deacock, a former major in the SAS who had established the Outward Bound School in Australia, decided they should do it themselves. He signed up a party of men he’d like to join them (they were 10 in all); the only thing missing was money, provisions – and a boat.

“Warwick had quite a bit of experience in organising expeditions,” says Budd, “and he was a very capable entrepreneur.” He remembers a meeting in Murdoch’s office at the recently launched newspaper with Deacock and Colin Putt, the group’s engineer, where the deal was swiftly done.

“The expedition needed press coverage,” says Budd. “Of course a polar expedition has always been a handy thing to keep people reading, and so it was arranged.”

The newspaper put up £6000 (the price of a small house in those days) for press rights, assigned two reporters to the job, supplied a huge ocean-span radio for the boat and arranged for extensive coverage in The Australian and elsewhere; but the adventurers were especially touched that the newspaper’s proprietor privately made extra efforts to ensure their success.

Deacock, who died in 2017, was always thankful for the generous support of Murdoch, whose company produced brochures for the expedition to assist in raising more sponsorship, and who personally worked behind the scenes to secure other endorsements.

“Rupert really went way beyond the strict terms of our agreement,” Budd says. “We rather suspected he spread the word around the clubs that this was a worthwhile effort, and worth backing. He was very kind. He was even helpful with people getting jobs after they came back. Colin summed it up for me: ‘Oh I think Rupert’s a good bloke,’ he said.”

A 69-foot (19m) gaff-rigged schooner, steel-hulled with six watertight bulkheads, was chartered from Strahan in Tasmania, where she’d been gathering crayfish, and brought to a donated berth at the Cruising Yacht Club in Sydney’s Rushcutters Bay.

There the Patanela was overhauled, refurbished and repainted by friends and volunteers, then packed with provisions and all the gear necessary to carry the crew to Heard and back, a journey of four months. Rolls-Royce, invited to examine her 165hp engine, returned it looking suspiciously new, at no charge. “They were just making sure their reputation was unblemished,” Putt said afterwards.

Other sponsors soon came on board, fired by the team’s spirit of adventure or amused by their cheeky requests: Corn Flakes from Kellogg’s, Big Ben pies (they asked for 500 but received a generous 2000), two barrels of rum from CSR.

On November 5, 1964, they set off through the Heads. An English skipper, 66-year-old HW “Bill” Tilman, a celebrated mountaineer turned sailor and travel writer who had fought with distinction in both world wars, was engaged to sail the vessel way west through the Horse Latitudes, then south to ride the fierce westerlies that would power them to Heard. (This was, of course, decades before the invention of GPS and satellite phones.)

When land appeared on the horizon on the appointed day, after weeks of some of the roughest seas imaginable, Tilman (“a seven-word-a-day man,” according to John Crick, at 22 the youngest of the team) was affronted by the crew’s joyous congratulations on what he saw as a straightforward piece of navigation.

(In a double-mystery postscript, both Tilman and the Patanela were to disappear at sea: Tilman in 1977 as a crewman on En Avant, somewhere between Rio de Janeiro and the Falkland Islands; the Patanela vanished within sight of the lights of Sydney’s Botany Bay on a November night in 1988.)

Five men were landed on the island – their dinghy capsizing in the savage, freezing surf – and began climbing to establish a base camp high on the mountain. After a week sheltering from filthy weather, they woke in their snug tent at 3am on January 25, 1965, to brilliant blue skies. They raced to the top, where there were a couple of minutes for photographs, then the weather turned and so did the party, trudging through another blizzard to the relative comfort of the beach. There they passed a fortnight doing scientific research while they waited for the Patanela, moored in the nearby Kerguelen Islands, to collect them.

As part of their sponsorship, another £6000 had been handed over by a producer for rights to the 11,000 feet of cine film that would be taken by Deacock and Malcolm Hay; and here the story leaps forward into the present day.

While the BBC had made a short film using their footage, it was the expeditioners’ one great regret that a full-length, professional documentary had never been created. When the rights eventually reverted to Deacock, he found the film had been cut – literally – into small pieces and it was a task well beyond him to splice it together. He and Budd tried over the years to interest television executives and film producers in the project, but to no avail. “Warwick died before he saw anything happen,” Budd says.

Then celebrated documentary director Michael Dillon, who was Sir Edmund Hillary’s long-term filmmaker and as a teenager had met Deacock through the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award scheme, decided to take on the challenge.

The result is The Great White Whale, 104 minutes of remarkable footage, with a score by Australian composer Paul Jarman, narrated (and sometimes sung) by Crick, and featuring interviews with his former shipmates.

It was a project of pure passion for Dillon; he and his wife financed it themselves, drawn, he says, to “this amazing, forgotten, Australian story. And it’s one I knew about from the beginning, as I was one of the many who volunteered to get the yacht ready”.

The film is at times chilling (and not just in temperature); the naked danger in pre-health and safety days feels tangible and immediate. But it also gives a lively sense of the excitement of the expeditioners, enriching a beautiful adventure documentary with great humanity by capturing their characters and the self-effacing good humour essential to hold them together over so many weeks. (Budd’s rendition of the Marseillaise to members of a French weather station on Kerguelen, however, shows why copious wine and the playing of the recorder should never be mixed.)

Dillon, who in 2022 was awarded the grand prize for lifetime achievement by the International Federation of Mountain and Adventure Film Festivals, had been sending evolving iterations of the film to overseas festivals; an unfinished version in December won the top prize at the International Mountain and Adventure Film Festival in Bilbao, Spain. This Saturday afternoon in Melbourne’s Cinema Nova, where it can command the big screen it deserves, the finished film’s gala premiere will form part of the Melbourne Documentary Film Festival; with luck, a savvy distributor will soon bring it to audiences all over the world.

For Budd, Dillon’s “raw courage in devoting more than a year of unfunded full-time work, and covering the costs of his talented team of co-workers”, wrote the missing final chapter of the 1964 story.

“This was the third great gamble of the expedition,” he says, “after Rupert Murdoch’s and Warwick’s own courageous gambles with a challenging new paper and a challenging expedition. I regard Mike as the 11th member of the crew.”

After numerous visits to Antarctica since that first ascent, including several more voyages to Heard, Budd, now 94, is a legend among expeditioners. He is the acknowledged world expert on the island, and a renowned medical researcher into the physiological effects of extreme temperature on the human body (that body often, judging by some alarming photographs of frostbitten hands, being his own).

Budd was made a member of the Order of Australia for his work in Antarctica, but next month he will receive an honour his fellow explorers will regard more highly: ANARE’s Phillip Law Medal, named for the founding director of the Australian Antarctic Division, and awarded annually for “outstanding contribution to Antarctic affairs and the Antarctic community”.

Asked about Law’s significance, Budd says: “There’s nobody I’d rather have my name with on a medal, because Phil was just the man we needed for those early years. He really stamped the character of the place.”

The medal surely adds Budd to an exclusive list of Antarctic royalty, but he demurs at the suggestion. “I just hope I’m worthy to be in their company,” he says.

For details of future screenings of The Great White Whale, go to michaeldillonfilms.com.au

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout