Beijing huffed and puffed – but couldn’t touch Australia’s strategic resources

Canberra should keep in mind the lesson from the bruising, last three years of trade bans: for all its bluster, China needs us too.

One good thing about the implosion of Australia’s relationship with China was that it taught us an important lesson: our biggest customer is far less powerful than many had feared.

For three years, Beijing huffed and puffed. It has caused ongoing misery for China-dependent Australian wineries and our lobster and timber industries. But those are just garnishes on Australia’s total trade to China. The entree, main course and desert are all strategic resources: iron ore, LNG and, increasingly, lithium.

China’s government didn’t dare touch any of them. Instead, Australian exports to China hit a record $180b in 2021. That may be old news in Australia, but it is still being studied around the world.

“Like a surfer surviving a shark attack with no more than a lightly gnawed board, Australia is now emerging from three years of Chinese bullying in remarkably good shape,” The Economist recently observed.

A second good thing about the collapse of Canberra’s relationship with Beijing is personal. Since 2021, I have been lucky enough to cover the region from Taipei, one of East Asia’s gems.

I still have a soft spot for China’s capital, where I was previously based, but there’s a lot to like about relocating to Taipei. The air here is much cleaner than in Beijing. Police don’t block me from visiting tourist spots because I’m a journalist. VPN headaches are a distant memory. None of my friends here have been put in jail on national security charges.

And ministers in Taiwan’s government accept requests for interviews – something that never happened in China.

Living here has also been a useful education in just how strange Canberra’s relations are with Taipei. The paranoia around a visit by Australian parliamentarians last November was illustrative. Our diplomatic office in Taipei is perhaps the most anti-social in the entire Australian network. No Australian minister has visited since the Rudd-Gillard era.

Gough Whitlam switched recognition from Taipei to Beijing in 1972. Since then Australia has had unofficial relations with Taiwan (which is officially called the Republic of China) – recognising, but always with a flexible ambiguity, Beijing’s claims on the self-governed liberal democracy.

Until Beijing renounces its threat to launch war on Taiwan’s 23 million people if they ever move to become formally independent, Australia’s tortured “One China” formula will remain. Complaining about it is as useless as moaning about Taipei’s humidity. A more productive approach is to pursue mutually beneficial policies within it.

For Australia, the ultimate test of this is Taiwan’s application to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

Joining would not in any way breach Australia’s “One China” policy. Taiwan would simply follow the path it took to join APEC in 1991, back in the Hawke-Keating era, and the World Trade Organisation in 2002, when John Howard was Prime Minister.

In our interview in his office in Taipei, Taiwan’s Trade Minister John Deng told me his government is not asking for special treatment. It only asks for Taiwan’s application to be assessed on its merits.

Asked about Taiwan’s chances of success, Minister Deng told me: “No one has ever told us to our face, ‘We don’t welcome you’.”

But what do the CPTPP’s members, including Australia, say behind Taiwan’s back?

In all my discussions with officials and politicians from member countries, including Australia, none has ever said they doubted Taiwan’s economy could meet the CPTPP’s high standards. But their fear of Beijing is palpable.

Canberra has good reason to push a serious discussion on Taiwan and China’s applications until after Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s trip to Beijing, likely in October.

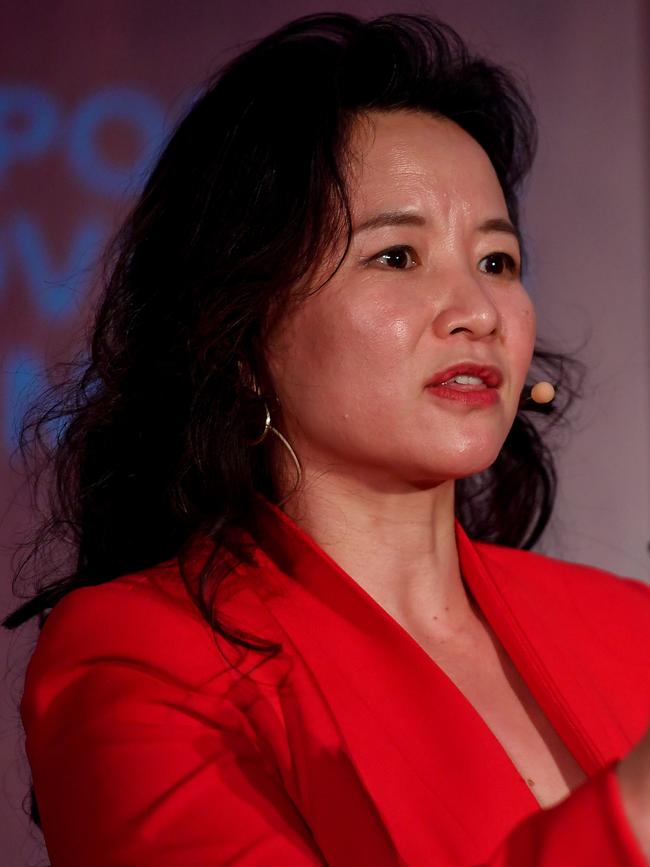

Australia’s vote gives it useful leverage over China, as Canberra pushes for an end to Beijing’s ongoing trade bans on Australian exports and tries to secure the release of Cheng Lei and Dr Yang Hengjun.

Of course, Beijing would suffer an epic outbreak of hurt feelings if the trade group’s members formalised the bleeding obvious and recognise that, right now, Taiwan’s economy is more CPTPP fit than China.

But if Beijing is serious about eventually joining the world’s highest standards trade pact, a campaign of retribution against a merit-based decision by its members wouldn’t seem to be the best response if Taiwan gains admission before China does.

When decision time comes, Canberra should keep in mind the lesson from these bruising, last three years: for all its bluster, China needs us too.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout