Battling virus outbreaks: the long and short of it

There is a growing argument that lockdowns are of questionable value when it comes to tackling small-scale COVID outbreaks.

Mark McGowan chose freedom over lockdowns for West Australians on Sunday.

In some ways it was grudging freedom. About 45,000 AFL fans were told at the last minute they could not attend the West Coast Eagles-Freemantle derby — the biggest thing in football in the west.

The Premier continued a mask-wearing mandate he had imposed the week before, and Perth nightclubs were ordered to shut their doors for seven days. But Perth residents remained free to leave their homes and go about their business.

Mr McGowan bristled at comparisons with NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian who has consistently resisted Sydney-wide lockdowns to deal with outbreaks. But the decision comes a week after he locked down Perth even as the outbreak failed to spread to a single case beyond the initial scare.

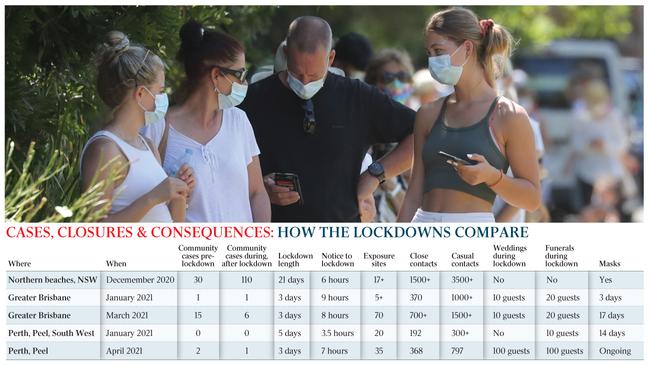

This has been a familiar pattern in recent snap lockdowns in both Perth and Brisbane. Once the initial outbreak is identified, it has failed to take root in the community, raising questions about the need for short-term lockdowns.

Peter Collignon, a microbiologist at the Canberra Hospital and a professor at the Australian National University Medical School, believes several factors are working in Australia’s favour as it battles the virus.

The effective use of contract- tracing teams, warm summer and autumn weather, good public hygiene and distancing measures, and the lack of so-called “superspreaders” have all acted to prevent large-scale infection, according Dr Collignon.

He said NSW and Victoria had handled similar larger outbreaks — NSW’s Berala and Victoria’s Black Rock outbreaks over the new year — without having to confine large populations in their homes.

“Those were contained without locking down an entire city, and often with a lot more cases too,” he said. “But that doesn’t mean you don’t put restrictions in place, like wearing masks if you are indoors or limiting the number of people who can come to households.”

Dr Collignon argues lockdowns become an important tool when there are multiple cases of community transmission of unknown origin, putting pressure on contact tracers.

Adam Kamradt-Scott, an expert in global health security and a non-regional affiliate with Georgetown University in Washington, says short-term lockdowns have become more of a political tool than a health one.

He said the NSW approach would be held up in the future as the prime example of how to handle pandemic, noting that the state had successfully managed hotspots and effectively contained localised outbreaks without automatically defaulting to extreme interventions.

“I still have reservations about the need for these three-day lockdowns, principally because I think most public health people would really agree you’re not going to accomplish a whole lot in three days,” he said.

“I understand politically that leaders want to be seen to be taking swift action and we all want to avoid the risk of further spread. But the practical benefits of a three-day lockdown are highly questionable, and if the contact-tracing systems aren’t already in place a three-day lockdown is not going to be particularly beneficial.”

Not all agree.

Kirsty Short, an Australian research fellow at the University of Queensland’s School of Chemistry and Molecular Biosciences, says that while short-term lockdowns should not be an automatic response to a quarantine breach they were a proven tool.

“If you are going to act, you have to act early and in that sense these short lockdowns are very much in line with that,” Dr Short said. “Thankfully, these short lockdowns have meant we haven’t had to have a longer lockdown so in many ways it’s a very responsible approach.”

While there is a growing body of evidence that lockdowns over one or two cases are of questionable value when there are established contact-tracing teams in place, the difficulty for governments and health authorities is determining when an outbreak is of sufficient scale to warrant such intervention.

Contact-tracers can be swamped if the number of cases hits 20 or more, Dr Short said, at which point the number of close and casual contacts of those infected cases can climb into the thousands.

Governments needed to consider lockdowns before an outbreak reached that point. The other uncertainty was whether an infected patient turned out to be a “super spreader”.

For a virus of such proven menace, the vast majority of people who contract it did not actually spread it to others. But about 20 per cent of COVID patients were responsible for about 80 per cent of COVID infections, Dr Short said. “There is a little bit of luck as to whether the individual infected is a super spreader or not, and we still don’t have a good understanding of what makes a super spreader,” she said.

“Certainly there are social and environmental factors. If you are an individual who is highly active in the community you’re more likely to be a super spreader, but there’s also probably biological reasons for it that we don’t fully understand either.”

The likelihood, when there is a single case that breaches quarantine, is that that person will not be one of those super spreaders.

The difficulty arises when one of those cases does end up being particularly effective at passing the virus on to others.

A super spreader was suspected as being behind the outbreak on Sydney northern beaches last summer, which did eventually prompt the introduction of a lockdown.

Mr McGowan has cited the northern beaches outbreak as an example of why early intervention was critical, labelling that prolonged situation as an example of what happens if short, sharp lockdowns are not called soon enough.

“Sometimes these things are forgotten, but Melbourne went through a five-day lockdown recently. Brisbane had a three-day lockdown recently. NSW had ongoing lockdowns for weeks and weeks and weeks; it actually cost NSW economy $3.2bn, what happened in the northern beaches there,” he said.

While Mr McGowan said Sunday’s decision not to call a lockdown was not a change in the government’s approach, there were signs even before the weekend that a more moderate response was evolving.

The state’s Anzac Day weekend lockdown was a pared-back version of the lockdown it called in January, when a quarantine hotel security guard contracted the virus. Last month’s first outbreak was a more serious one, given the patient at the centre of the event had been shown to be capable of transmitting the virus, but the lockdown was only three days as opposed to five in January.

Weddings that were cancelled earlier in the year were instead capped at 100 guests this time, while mask requirements were softened from a few months ago.

But the fact remains that Western Australia’s containment of the outbreak — in which two million people were forced into lockdown — was just as effective as that by NSW around its recent Byron Bay outbreak, where the most onerous restrictions imposed were limiting a shire of 30,000 people to having no more than 30 people to their parties and cancelling Bluesfest.

The economic costs of lockdowns are significant.

Mr McGowan said the state’s Treasury department estimated the recent three-day lockdown would cost the economy $70m, although WA’s Chamber of Commerce and Industry estimated the cost at $170m.

Innes Willox, the chief executive of Australian Industry Group, said a citywide lockdown cost an economy about $1bn a week.

He said the successes of containing the recent infections, both with and without lockdowns, show that lockdowns were an “over-reaction” to small outbreaks.

While all the recent outbreaks had been successfully contained, Dr Short said the leakages out of hotel quarantine showed that the virus remained highly contagious.

She said the various successes around the country showed that the message of “track, trace and test” was working.

“There’s a reason Australia has been able to contain this, and that’s because we’ve taken the public health response very seriously,” she said.

One argument in favour of short lockdowns is that they focus public attention on the risks at hand. A population that has grown complacent about hygiene, distancing and checking can be stirred into action by such a step.

But, Dr Collignon said, more moderate, less costly restrictions may be able to deliver the same result. “So far, of the eight short lockdowns we’ve had here and in New Zealand, I can’t see any evidence that it’s found more cases or prevented any infections other than what we’ve done anyway,” he said. “And it’s done that at a cost of social and economic hardship.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout