Australian Bronwyn Trathen endured the horrors of solitary confinement in a Greek jail 50 years ago

Fifty years ago The Australian reported a young Sydney woman had been arrested and jailed in Greece for having her boyfriend stay in her apartment. We’ve tracked her down to hear her story.

Stories don’t end when they hit the news. For The Australian’s 60th birthday, FIONA HARARI retraces a story for each of the past six decades

Most people who know Bronwyn Trathen today have no idea about her time in a Greek jail. They know nothing of her disappearance from her Athens apartment in the middle of a military junta, how she was bundled into a car, interrogated, then kept for weeks in solitary confinement, a strip of light below her cell door one of her few connections to the world.

“I never talk about it,” she says quietly at the northern NSW home where she has lived with a backdrop of birdsong for 17 years. “Since I’ve been here, I don’t think anyone knows.”

Fifty years, however, have not expunged her memories of those tumultuous months in 1973 and 1974, the fear and uncertainty as she was sentenced to a year in a foreign jail for harbouring a fugitive – her law student boyfriend – in a country she adored.

Greece was in the grip of a military dictatorship when Ms Trathen arrived in 1969, a 23-year-old Sydney woman in search of a wider world. Her aunt, a UN translator, and her Greek-born uncle lived in Thessaloniki so she headed there. But she found the city’s strict social norms stifling – resisting her uncle’s suggestion that, as a young single woman, she only walk alone if she donned a wedding ring – and moved to Athens, where she worked as an English teacher.

“I just fell in love with the place,” she says now, at 77. “The people, they knew how to live.”

She adored the late-night lifestyle, the conviviality that often broke out among tables of strangers in restaurants, the vibrancy of the locals that was such a contrast to home. “My parents (her father Douglas, a former principal of Newington College, opposed conscription during the Vietnam War) were very reserved,” she says. “They never got angry. They were never violent. You only knew someone was unhappy because the door would slam.”

In Athens, there were crowds and noise, and in her top-floor Pangrati apartment, from where she could smell the aromas of a filo pastry shop, she felt safe, even as the military hold on the city tightened.

Portentous meeting

At a party at the Australian embassy in the early 1970s, she met George Charalambopoulos. He was charming and swarthy, with dark hair and amber eyes. “We talked and talked and talked,” she recalls of her first meeting with her first love. “I felt very at home with him. He spoke beautiful English and he was very kind.”

He was active in student politics. “Occasionally George would stay with me for a few days at my place and students would come and have a meeting,” she says.

Surrounded by politics, and interested in what was happening, she was, she says, no activist. “People I knew who were involved would talk to me freely, particularly because I was a foreigner.”

Nor was she initially concerned about the meetings.

“And then at the third meeting there were these other people, older guys, no women, and I didn’t feel comfortable with them,” she says. “And I told George that I wasn’t happy with these people coming, they were strangers, they weren’t students.”

While the older men never returned to her apartment, the events that subsequently unfolded in her Athens home and beyond would have dire consequences.

Strife breaks out

On December 21, 1973, Ms Trathen woke to commotion. In the wake of November’s mass anti-junta revolt at the Athens Polytechnic, which resulted in 24 deaths, Mr Charalambopoulos had moved in with his girlfriend temporarily. The son of a politician who had been forced into internal exile under military rule, the younger Mr Charalambopoulos was awaiting a passport, and was planning to go into hiding.

“Even though he didn’t have anything to do with the Polytechnic – he was still doing his military service – he had been active (in student politics) and people were saying ‘You need to go’,” she says.

As the young Australian walked towards her front door on that late 1973 morning, she found several military officers and a young man in civilian clothing seeking her boyfriend. Soon she and Mr Charalambopoulos were herded into an unmarked car, surrounded by soldiers. “George looked white as a sheet,” she says of their terrifying exit. “I always remember him holding on to my shoulder and nothing was ever said.”

Interrogations begin

They were driven to another part of the city, to what seemed at first like an administrative block. Much later that day she was interrogated “by a great big fat man, and they were accusing me of going over the border and causing trouble”.

She remembers insisting she had not been involved with politics, that she had nothing to do with a meeting of older men at her flat, and that her boyfriend could not have been at the Polytechnic in a red beret during the uprising. As the accusations mounted she also remembers that she stopped listening. “It was as though I just withdrew myself up to the ceiling and I was looking down at myself,” she says.

Eventually she was led to a freezing cell, with one light bulb and a blanket. She spent the next three weeks there mostly alone, watching birds nesting through a high, barred window, doing yoga to still her mind, not entirely clear of what she was accused, and unsure if anyone knew where she was. “The concept you see on television, where people have someone to ring up, or a lawyer to get, it wasn’t like that,” she says.

Physical toll

With the light on constantly, her sleep deprivation was compounded by the irregular crashing of metal bars. “It didn’t make sense to me that they would hold me. I hadn’t been involved in anything,” she says of the exhaustion and bewilderment she experienced.

Unable to shower, even when she had her period, her body was soon covered in sores. To protect her sanity she began to sing aloud. During a rendition of Scarborough Fair one day, she was joined by other voices and only then did she realise there were possibly a dozen other people in cells around her, among them, she noticed as her door was opened one day, her boyfriend’s politician father, Ioannis. From their screams, she realised her luck at not being tortured.

“I tried not to think about George at all at that time,” she says now. “I was trying to keep my balance. The thing that I thought would be the worst was if I started to panic.”

After three weeks she faced another interrogation and was presented with a confession that, through her unstated knowledge of Greek, she realised was untrue. Accused of harbouring a wanted criminal, desperate and sleep-deprived she signed it anyway. “I didn’t argue. I didn’t say anything. I was mute during the confession.”

She was driven next to a military area in another part of Athens. This time her cell was tiny and had no window. When her door was locked, she was left alone in the confined space in almost total darkness, her only guide a sliver of light on the floor. One day it revealed a note that had been left for her. It was from her boyfriend, who was being detained in the same military facility and who had been able to enlist the help of a cleaner to contact her.

That sign of life was a rare moment of joy in a period that was mostly dark. Over the ensuing weeks she heard more screaming, and the hysterical sobbing of a tortured man crying for his mother. “And that really undid me,” she says.

Alone and barely able to move in her confined cell, she remembers shaking uncontrollably.

Consular help

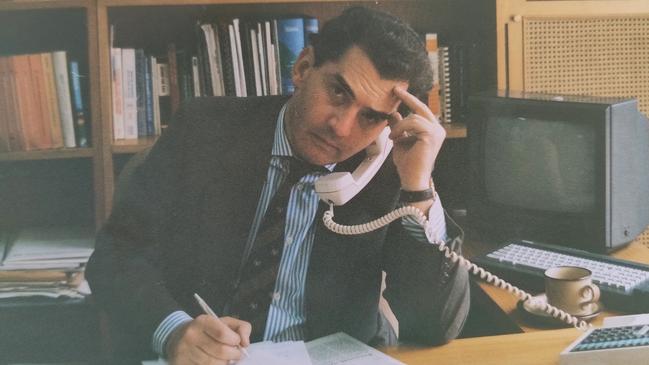

Only when she was moved to a third jail, after more than a month in solitary confinement, did she finally have access to consular help. By then her story had broken at home. On Australia Day in 1974, she was page three news in The Australian, charged with “disobeying orders of the military authorities”.

An American friend, who had been unable to locate her, had alerted Australian embassy staff two days after she went missing, but they were only finally able to visit the Sydneysider after she had been imprisoned for over five weeks.

Among the belongings consular officials delivered to her was a photograph of George Charalambopoulos (spelt Haralambopoulos in many reports at the time).

Fifty years later, the memory of that moment remains deeply emotional, and for several minutes she is unable to speak. “They didn’t know where he was,” she says eventually, her suppressed fears for his safety erupting at the sight of his image.

Day before justice

When she finally faced court, unwashed, afraid and shaking, she faced three judges, charged with hiding a fugitive and failing to let police know she had someone staying in her apartment.

She looked likely to spend a year in jail. But her lawyer pleaded for his young client’s freedom, arguing her innocence, and that her detention was resulting in Greek shipping being held up in Australia. “And suddenly,” she says now, “it was all over.”

She was placed in an embassy car and driven to the airport. Having showered once in 10 weeks, now, without washing or a change of clothes, she was returning straight home. On the way to Athens airport, embassy staff handed her a wad of letters from supporters, some of whom had also enclosed money.

“And I realised that the world is actually full of people who are quite wonderful and loving,” she says quietly half a decade later, “and there are people who are quite evil.”

Back … but not for long

Landing in Sydney, where she was taken from the plane to a remote area of the airport to avoid the waiting media, she was overwhelmed. “When you’ve been a really independent person and controlled all your life, and suddenly you don’t have any control, I was like a stupid person,” she says.

Sixteen kilograms lighter, she was driven to her parents’ new home in Chatswood, media waiting outside, and where, bedding down in the dining room, she was unable to sleep for days.

There was little overt support back home. “My parents didn’t say anything. They left me to do nothing and my father allowed (a journalist) to come and interview me.”

Chatswood was “devastatingly boring” in 1974 and she “felt out of step” for so long that later that year, the military dictatorship finally over, she returned to Greece. She reunited with Mr Charalambopoulos, but the man to whom she soon became engaged was also broken. Before he was released from prison in March 1974, he, too, had been tortured.

“George wasn’t himself,” Ms Trathen remembers. “In the past he would argue and disagree with his father but now it seemed as though he had lost all ability to be an assertive person.”

Turning point

Eventually their engagement ended. “I started to have concerns. I saw them (George’s family) as having a different value system,” she says.

But more than anything there was a tacit emotion lurking in the bridge between the pair’s past and their future. “I was very aware that George felt terrible guilt, and to see me there just reminded him of what had happened.”

George Charalambopoulos became an international lawyer, married three times and had five children. His father, Ioannis, resurrected his political career, eventually becoming Greek foreign minister. He died in 2014.

Ms Trathen remained in Greece for a few months in 1975 before returning to Australia, where she later studied urban sociology, taught English, earned a masters in design and had several relationships.

In the 1980s, while planning to make a film about those tumultuous times, she returned to Greece and interviewed her first love. Only then, she says, did George make a confession. “He said, ‘You were used’. He used me by having people come and have meetings at my house, because that was how the junta had my name and my address and came to arrest us,” she says.

History has its own strange rhythm, and what-might-have-been does not always figure in it. “George,” she says, “was very much a part of my life in Greece. But as time goes on, we would have probably parted anyway because I had other interests apart from politics.”

And the lingering effect of those few terrible months? “I got out of that, I was sane, I handled it – that gave me huge confidence,” she says. “Because I survived. Because I was able to not succumb.”