It was a decade dominated by the true reformers, an era that transformed Australia and galvanised a new sense of national self-confidence and ambition. The economic story of 1980s Australia opened with stagnation and ended with the “recession we had to have”, but the reforms achieved throughout the Hawke-Keating era were seismic – casting aside the old protectionist consensus and embracing the new, modernising forces of financial deregulation.

At the end of 1983, The Australian’s editor-in-chief Les Hollings interviewed Bob Hawke, naming him the paper’s Australian of the Year, as well as the “people’s Prime Minister”.

“We have picked him not only for his stunning election victory and his achievements during the year,” Hollings wrote, “but also for the high expectations Australians hold for him in 1984.” Hawke’s election campaign was “consensus politics”.

The slow breakdown of the Hawke-Keating relationship did not become public knowledge until the 1990s but the tensions that boiled over into their historic leadership struggle began to emerge by the late 1980s.

In April 1988, The Australian’s then national affairs editor Paul Kelly noted the growing disconnect between the two Labor heavyweights, writing that if “Bob and Paul are going to be in tandem for the next three years they had better start talking a lot more”.

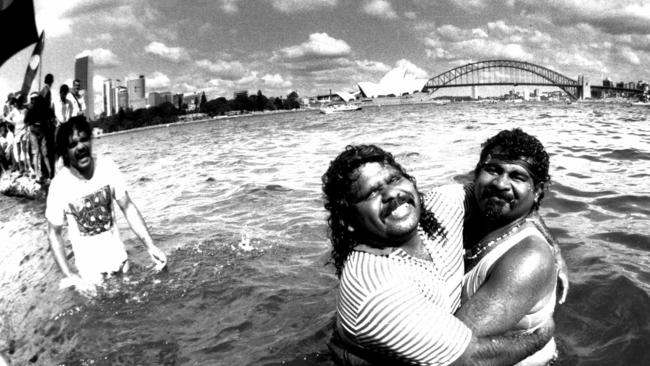

A NATION CELEBRATES

It is worth calling to mind some of those achievements. The first thing the First Fleet had to do was to survive. Because of the reverse cycle of the seasons down under and the unsuitable crops the troops tried to plant, starvation was a serious prospect, and it is nothing short of amazing that within 50 years a fairly prosperous, civilised settlement had been produced. What is really staggering, however, is that within 100 years of our first settlement, Australia had the highest living standard in the world. Politically, Australia has in some ways led the world. At the heart of our experiments in democracy has been the egalitarianism of a society in which former convicts could become wealthy land owners and even colonial officials.

The secret ballot became known as the “Australian ballot” in many countries, because the first secret ballot for a parliamentary election was conducted in Victoria in 1856. Women gained the vote in South Australia in 1894, just one year after they did so in New Zealand, which was the first polity in the world to enact such a reform. Australia has been a remarkably tolerant society, notwithstanding the obvious mistreatment of the Aborigines in the early colony. The Jewish general John Monash, Australia’s leading general of World War I, probably occupied the most senior military position of any Jew since biblical times. Sir Isaac Isaacs, Australia’s first Australian-born governor-general, was also Jewish. This was at a time when much of the so-called civilised world was gripped by virulent and filthy anti-Semitism. Since World War II, Australia has absorbed many more than two million immigrants from many lands around the world, including more than 100,000 Indo-Chinese refugees. It has been a remarkably successful absorption, with no major organised intercommunal violence, no racist parties getting any significant votes, nothing even remotely equivalent to the National Front in Britain.

In the world of literature, the early bush balladeers established an Australian voice and an Australian identity, but more serious artists came to take their place. Poets like Ken Slessor and James McAuley explored the Australian identity from differing perspectives. In Les Murray we now have one of the most significant poetic voices active in the English language. The novel as one of the highest forms of artistic expression has also flourished in Australia. Patrick White achieved the great recognition of the Nobel prize for Literature in 1973, but before him Martin Boyd and Christina Stead had established the seriousness of the Australian novel. The glorious climate that much of our country enjoys has naturally led to a love of sport. But sport is more than a way to enjoy the good weather, it is a way for Australians to participate in the world and to test ourselves against the best there is. In Sir Donald Bradman and Rod Laver Australia has produced two men who have serious claims to being regarded as the finest athletes their respective sports have ever seen.

On this happy day we have a right to be a happy nation and to bask for a moment in contented reflection on 200 years of remarkable achievement.

‘THE PEOPLE’S PM’

- By Les Hollings. First published December 31, 1983

The Australian has chosen the Prime Minister, Mr Hawke, as Australian of the Year. We have picked him not only for his stunning election victory and his achievements during the year, but also for the high expectations Australians hold for him in 1984.

Mr Hawke is a people’s Prime Minister. He fits in wherever he goes. Readers of The Australian mentioned the hope he has given the community and those who nominated Mr Hawke say they are looking to the future of Australia rather than past achievements.

At the end of 1983 we seem to be more interested in ourselves as a nation and the image we project. The world seems to be more interested in us. We leave 1983 more optimistic than we have been for many a new year …

The return of the Prime Minister’s Cricket XI for the first time since the Menzies era is another example of his touch. The main platform in Mr Hawke’s election campaign was consensus politics. He promised to consult and try to bring opposing sides together to reach a mutually agreed position. That was what his economic summit was all about.

Regardless of whether one believes this policy has worked, we did have a less divisive year in which there has not been a major strike. We have suffered in previous Christmas periods: this time a few unions uttered threats of strikes but none was carried out. The economic summit brought a return to wage indexation which not all of us agree with.

We all know in our hearts we should have continued with the wages freeze for another six months. But what the summit and its results brought to the economic scene was more certainty in economic planning. If business did not agree with the 4.3 per cent wage rise that ensued, at least it knew with certainty what wage costs were and with only tiny exceptions strikes did not blow this figure out to more than it was supposed to be.

Mr Hawke’s trip to the United States was a great success. He acquitted himself well and he quelled fears among the influential American investment community about the future directions of Australian government policy. The media here and in the US judged it to be a masterful performance.

Although a new boy, Mr Hawke made his mark at the Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting in Delhi later in the year and impressed many of his fellow leaders, especially in the area of foreign affairs.

Mr Hawke had a narrow victory in Caucus to allow uranium mining to proceed in South Australia. This was a step forward for this economically troubled state, but in the ensuing weeks great damage was done to the Northern Territory’s potential for uranium mining and the Labor Party paid the penalty for this in an overwhelming defeat in the Territory elections.

Towards the end of the year we had better economic news. The recession appears to be over and we can look forward to a more prosperous year. The upturn was due partly to the revival of rural industry following the drought, the continuing upturn in the United States which is having a beneficial effect on other key economies in the world and the effect on the previous government’s wages freeze.

The Australian business community seems well pleased with the performance of Mr Hawke’s government. There has been a general freeing up of the market, culminating in the floating of the Australian dollar which inevitably will lead to the entry of foreign banks and more competition within Australia in the banking system.

The fact the dollar has been freed will cause us all to exercise more self-discipline. There is less likelihood of the government intervening to move the dollar one way or the other to protect sections of the Australian economic life from the effects of their own actions.

The expectations of Mr Hawke are that he has much to do. And as Mr B.A. Santamaria said in The Australian on December 20: “Since the Liberals are less an opposition than a laugh, into the five-year future Mr Hawke is the best available Prime Minister for Australia.”

Australia has changed in the past year or so. We are rushing to watch Australian programs on television, to see Australian films and to read Australian books. We no longer feel it unfashionable to show pride in our country and to hope fervently and openly for its success.

Perhaps it was because of the recession but, for whatever reason, we are more ready to respond to initiatives to put right things that we know are wrong. We may even be getting a little less selfish as we see unemployment grow and no end yet in sight to its growth.

Most of us have young people in our families and the future of Australia is their future.

For the good start that he has made and for the awe-inspiring expectations we hold for his future performance, we make Bob Hawke Australian of the Year.

Technology – and Channel Nine – came a cropper on election night in 1983, wrote Jane Cadzow. Comedy was the winner.

THE ELECTRONIC ELECTION

- By Jane Cadzow. First published March 7, 1983

Shortly before 11pm on Saturday, as the excitement in the tally room reached fever pitch, Senator Don Chipp turned to his colleagues on Channel Nine’s election commentary panel.

“Do you fellas agree,” he asked, choosing his words carefully, “that this is the … funniest final count we’ve ever seen?”

Indeed. Though the relative merits of the various networks’ election broadcasts are expected to be discussed for days, weeks, even years, one fact is indisputable. For sheer entertainment, for inspired high comedy of a kind rarely seen on Australian television, Nine was in a class of its own.

It might be argued that its selection of commentators gave it a considerable head start. Apart from Senator Chipp, always good with the one-liners, the panel included such well-loved and wildly charismatic personalities as George Negus, Andrew Peacock, Paul Hogan and Paul Keating, not to mention political journalists Max Walsh and Alan Reid.

However the star of the show, simply refusing to be upstaged, was the Channel Nine computer. As anchorman Jim Waley explained at the outset, its job was to provide an instant analysis of voting trends, thereby predicting the election result when only a fraction of the vote had been counted. This particular computer was “what you might call a crystal ball made of microchips”, Mr Waley said smugly.

For an hour and a half, all went according to plan. The computer obediently flashed rows of figures onto the screen, and the panel members had long and meaningful dialogues about the apparently irreversible swing to Labor.

Hogan to Peacock: ‘’Well, you’ve buggered it.” Peacock: “You reckon we’re really gone, mate?’’ Hogan: “I reckon you’re gone, yeah.” In living rooms around the country they broke out the champagne and prepared to dance the conga.

But wait. At 9.31pm the computer spewed out its first prediction of the final result – an 11.8 per cent swing to the coalition. Labor voters from Cairns to Colac took off their party hats and stared at each other in sickly disbelief. “It’s 1980 all over again,’’ they sobbed.

Mr Peacock, on the other hand, who had maintained all along that the Liberals had it in the bag, brightened up considerably. “The computer’s the only one who agrees with me,” he said.

Meanwhile the camera crossed to the Sydney home of Mr John Howard, where a party for Liberal campaign workers had just taken a dramatic turn for the better. The treasurer, looking rather more relaxed than usual, tore himself away to have a quick word with the Nine reporter waiting in the front garden.

He, too, had heard the news. It looked like the opinion pollsters were wrong again. “I think some people are in for some red faces,” he said, before weaving his way back to the house.

At 9.45pm the computer had another stab at predicting the result. This time the swing to the coalition was a whopping 27.2 per cent. Mr Peacock could scarcely believe his good luck. Others on the panel were becoming openly suspicious.

“I think Peacock’s sabotaged it,” Senator Chipp said.

“I frankly fear that our computer has blown a cathode ray tube or something,” Max Walsh said apologetically.

The microchip crystal ball was growing more reckless by the minute. In the seat of Barton it predicted a 104.5 per cent swing to the coalition. In other electorates with vote counts clearly indicating Labor victories, it cheekily insisted on swings to the coalition of up to 181.6 per cent.

There was more to come. Next on its agenda was the seat of Casey. Throwing the last vestiges of caution to the wind it predicted a swing to the coalition of 311 per cent.

It was at about this time that the smile faded slowly but surely from Mr Peacock’s face and the Labor voters put their party hats back on.

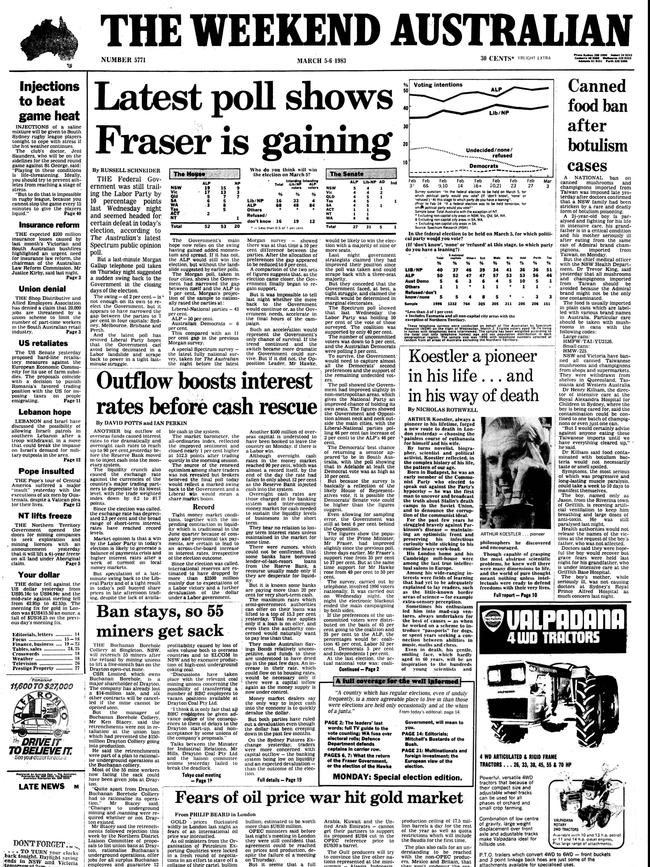

If Bob Hawke and Paul Keating are going to be in tandem for the next three years they had better start talking and work out how to play the increasingly difficult challenge

BOB AND PAUL BETTER START TALKING

- By Paul Kelly

The signal this week by the Treasurer Paul Keating that he will stay to fight the next election is an important step in the Hawke government’s efforts to restore its stability after the recent electoral reversals.

With Labor facing an uphill fight, Mr Keating could scarcely quit politics halfway through the present term, even if he wanted to, without being seen to be abandoning his responsibilities. The Treasurer is being locked in. The real danger of instability in ALP ranks has come not so much from recent indifferent performances of Bob Hawke – a periodic feature of his public career – but the speculation that Mr Keating, if denied the top job this year, may walk out of politics altogether.

The oft-made comparison with previous eras merely highlights how critical the Hawke-Keating partnership has been to the government’s success. It has always been obvious that Mr Hawke and Mr Keating together were superior to either of them alone. The leadership issue for the present parliament was always whether Labor could keep this optimum team together. Mr Hawke is not going to quit politics in a way that leaves open the interpretation that he is running from adversity. Mr Hawke’s popularity must be used by the ALP to improve the standing of the government against the opposition. The political and marketing challenge for the ALP will be to recast the government from its “non-caring” image which is doing such electoral damage.

The truth is that no Australian politician can promise higher living standards with any confidence. No government can deliver with certainty. Raising expectations that cannot be realised are potentially counter-productive.

If Bob and Paul are going to be in tandem for the next three years they had better start talking a lot more and work out how to play the increasingly difficult challenge.

To celebrate this masthead’s 60th anniversary on July 15 we are reflecting on the ways we covered the nation through the decades. See more from this series here.