Aussie crocs killing on foreign shores?

The doyen of Australian crocodile researchers, Grahame Webb, has spent the past three years pursuing an intriguing but horrifying possibility.

The doyen of Australian crocodile researchers, Grahame Webb, has spent the past three years pursuing an intriguing but horrifying possibility: that saltwater crocs from the Northern Territory are killing people in distant East Timor.

Part of the answer is now in – and it only raises more questions in Professor Webb’s mind as to whether an explosion in crocodile numbers in the Top End is behind the baffling, more than 20-fold increase in lethal attacks in the impoverished island nation to the north. There, crocodiles have killed people at the unprecedented rate of one a month.

A pioneering DNA sampling program launched in 2019, after a multinational team led by Professor Webb argued that Australian crocs were crossing 450km of open sea to find a new home, has found no genetic link between indigenous Timorese salties and those in the NT. This satisfied no one.

Professor Webb insists the testing was limited and the anecdotal evidence – including sightings of 4m crocs sunning themselves on oil rig infrastructure deep in the Timor Sea – still supports his theory.

And one of the lead scientists in the DNA project, biologist Sam Banks, agrees more work is needed.

“If crocodiles are making their way across to Timor and causing problems there, we have a moral responsibility to sort this out,” said Darwin-based Professor Webb, 73, who has been studying saltwater crocodiles since they were protected in Australia 50 years ago. “It’s also in our interest because understanding how and where crocodiles move is important to managing them here.”

After being hunted to the brink of extinction, crocodile numbers are now so high across Northern Australia that there are calls for the creatures to be culled. The wild population in the NT is estimated to be more than 100,000, while a survey completed by the Queensland government last month found 30,000 in that state.

The mauling of two soldiers last week while they were swimming off the Cape York Peninsula hamlet of Portland Roads, 800km north of Cairns, was the fourth croc attack in Queensland this year, heightening concern about the public safety risk.

One of the men was being “death-rolled” by the 2.5m predator when his companion intervened and prised open its jaws in a feat of strength and courage. The croc then seized the rescuer, gripping him until he used a knife to drive it off.

Crocodiles are intensely territorial and Professor Webb believes the competition for space in parts of the Top End could be causing displacement. In Australia, crocs are now turning up in places previously considered unsuitable for them.

The 2018 paper he co-wrote detailed how crocodile attacks in East Timor had climbed from roughly one every two years for 1996-2006 to 13 attacks a year from 2007-14, a 23-fold increase. A plausible explanation was that “the influx of large crocodiles attacking people are migrants from Australia”, scientists concluded.

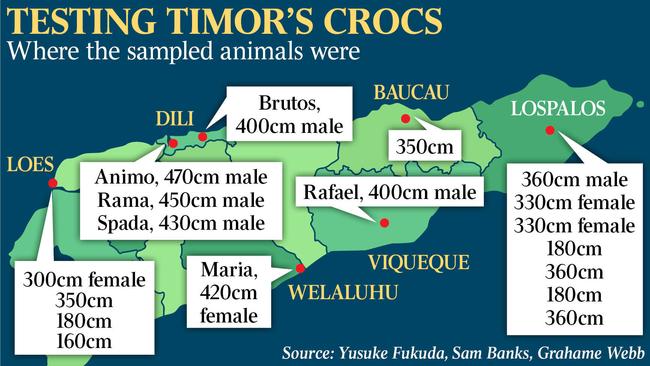

The DNA study, also involving Professor Webb, was set up to test the hypothesis. If Australian crocodiles were making their way north, they should have found mates in Timor-Leste, leaving DNA markers in the local croc population. Samples were taken from 18 local reptiles but none cross-checked with Australian salties.

Professor Webb insisted the results were far from conclusive. Most of the samples were from crocodiles on the country’s north coast, and if there was an Australian link it would more logically be found on the south side of the island, facing the NT. “That’s where we need to look and I am in the process of raising money to do that,” Professor Webb said.

Professor Banks, also of Charles Darwin University, agreed the possibility remained open that East Timor’s so-called “troublemaking” crocodiles were Australian. “We do need to go and get something more from the south coast … it’s the only way we will get a definitive answer.”

There’s a wicked twist here. While crocodiles are generally accorded a wide berth by Australians, they are revered in East Timor and locals, steeped in the country’s origin myth that the crocodile Lafaek Diak sacrificed itself to become the home of a boy it loved, cannot believe indigenous crocs would go rogue. Harming them is not only culturally taboo but illegal.

If newcomers from the Top End are responsible for the spike in attacks, it represents quite a feat of endurance. Professor Webb said it would take an adult crocodile up to a fortnight to swim the Timor Sea; if it made it to East Timor it would be ravenous and best avoided.

Adding weight to his belief the journey was possible were repeated crocodile sightings by oil rig personnel, far into the steamy ocean between the island and northern Australia. In one case, a croc was spotted atop a floating hose line from the Bayu-Undan platform, 300km off the NT coast. Another oil worker told Professor Webb he had seen a 4m monster resting on a moored barge.

Satellite tracking of relocated adult crocodiles showed they were highly mobile after release, and something similar could be expected from those arriving on a new coastline after a long sea journey. “Such movements bring crocodiles into areas where there are few resident crocodiles and where human behaviour, for example fishing on the coast in Timor-Leste, had previously been conducted safely,” the team found.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout