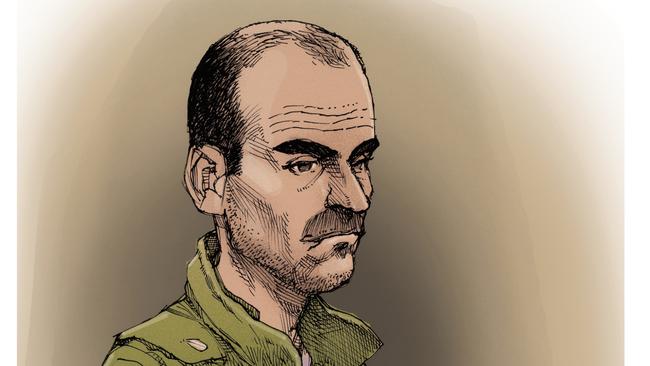

Ashley Paul Griffith: For victims’ families, there is only the ‘before’ and ‘after’

More than a dozen parents and now-adult victims have told of the moment they discovered childhoods had been shattered by Australia’s worst pedophile, Ashley Paul Griffith.

She was three years old when Ashley Paul Griffith started abusing her in childcare. Recorded her. Put her on the dark web.

A sweet, sociable, innocent little girl whose life started spiralling right at the time she was being horrifically violated by the daycare worker entrusted with her care and safety.

She was too young to verbalise what she was going through but her behaviour told a story.

She went from being a joy for all to be around to being anxious and timid and withdrawn from anyone outside the tight family unit where she still felt secure.

Every medical professional she was taken to asked the same thing: Had something happened? Had someone hurt her?

There was nothing, her parents answered every time, exasperated and feeling the weight of suspicion fall on them. But there was something. As they found out more than a decade later when police called after Griffith had been arrested and his electronic devices seized in August 2022.

The lives of everyone affected by Griffith has two parts, and this family was no exception.

There was the time before they were showed footage of their little girls being raped and abused, so they could identify them from their clothing.

And there was the time after, when through the fog of grief, guilt, disgust and most of all unbridled anger they have been left to wrestle with a question that has no obvious right or wrong answer: When, if ever, do they tell their daughter she was a victim of childhood abuse?

On Thursday, with shallow, shaky breaths, this girl and her mother told a court how the abuser had ruined their lives.

As many parents outlined over 2½ harrowing hours in Brisbane’s District Court on the first of two days set aside for sentencing, the great unknown is how the abuse will affect their little girls as they grow older.

Will they have a happy or normal life? Will their relationships be affected, will they turn to alcohol, drugs or self-harm?

Everyone’s worst fears about the impact of Griffith’s abuse was brought to life by one teenager.

In the “before”, struggling to connect, she had isolated herself and had been teased and bullied at school. Panic attacks followed minor events that would never have troubled her peers.

At first people said she was shy, but her parents realised something was wrong. She spent years cutting herself, went through therapy, on medication. “I had no idea why I felt so uncomfortable and scared. It’s very clear to me now,” the teenager said.

“It has been stated to me by my mental health professionals that I will most likely need ongoing therapy and medication for the rest of my life, just so I can do daily things that people around me are able to do.”

In the “after”, she found out there were at least 50 separate occasions where she was sexually abused by Griffith.

All of that horror has been rolled into a single charge that does not even come close to reflecting the crimes against her, and the damage inflicted. The charge is called maintaining a sexual relationship with a child.

For each of the 15 victims with this single charge, it means they were repeatedly sexually abused, sometimes over many months.

It means the 307 charges against Griffith for abusing 69 girls in Queensland does not reflect the true horror of his crimes.

Then there are the offences he is still to face justice for in NSW, where he abused dozens more children at one daycare centre. And crimes parents don’t know of.

“We believe there are likely more instances of sexual abuse that were not filmed and cannot be proven,” her mother said.

It is testimony that will hopefully end once and for all the fallacy that all of Griffith’s crimes have been identified.

There were small signs that were easy at the time for parents to miss. In this girl’s case, the trail of clues included her childhood nightmares about “the monster upstairs”.

Her family thought she was afraid of their new and bigger two-storey house; they now know who the monster was.

The girl was already at a crisis point, depressed and self-harming, when police called her parents. Would telling her of the abuse push her over the edge, or help her to understand herself?

They told her, and made sure they were with her 24 hours a day until they knew she was safe.

“How were we to know the greatest danger to our child was the one entrusted with her care?” the mother said.

She wasn’t to know, anymore than the policeman who for many years as a serving officer strongly advocated for child safety at his daughter’s daycare centre. He had no idea his little girl was being abused by Griffith.

Once, he attended the centre with colleagues in full uniform and with police vehicles.

“Ashley was there that day. All the centre’s children came out to the centre’s car park for a police safety presentation. The abuser was there with (his daughter). There he was, her protector. I told the children they could say no if they felt unsafe around adults.

“The abuser was listening and agreeing to everything I and my colleagues were saying.”

One victim’s mother said: “I work with the federal government childcare division, and it’s infuriating to see how little focus is placed on preventing predators like Griffith.”

Another mother received a goodbye email from Griffith when he moved on from a daycare centre, thanking her for the generous support over the previous year and a bit. He commented on her amazing family and her daughter’s joyful spirit and kind and loving heart, of the mother’s love of writing and the time she took in the mornings and afternoons to get to know him better as the main carer of her child.

At the time, she was mad he’d been asked to leave before he wanted to, and responded with thanks for his profound impact on her daughter’s life. Her daughter had been raped by Griffith.

The mother of another victim offered Griffith a lift home one day when she saw him walking to a bus stop from the childcare centre, and they became close friends.

He attended family birthday parties, played touch football with her teenage sons, went over for Sunday night dinners and Friday movie nights.

Her son told her: “You thought you were being Christ-like but you’ve literally let the devil into our home.”

Parents can no longer look at childhood photos of their children from that time, or see them sleeping, without thinking of the abuse.

In the before, they were normal families. In the after, many have decided to keep this unfathomable secret to themselves to see whether their daughters can lead normal lives. They dread someone giving their secret away.

They are asking how Griffith got away with it, and what’s going to be done beyond a prison sentence that will keep him from harming others.

Yet that will never be enough.