An under-the-radar voice campaign is sparking candid conversations about race, government and change

There are no questions off-limits at information sessions hosted by the Uluru Dialogue campaign in regional and remote communities.

In CWA halls and shire buildings across regional Australia, Indigenous men and women have been answering questions including “Is it true that you get free cars?”

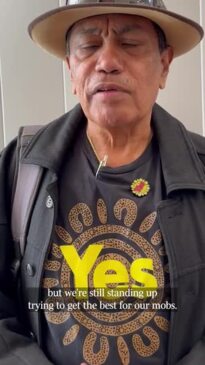

Geoff Scott, a Wiradjuri man from Narromine, says this is about making a “safe space” for non-Indigenous people who want to know the story of the Indigenous voice to parliament and why the Uluru Dialogue supports it.

Most members of the Uluru Dialogue campaign were in the room at Uluru when the statement was created in 2017. The conversations that flow in these information sessions – from the Daintree to Broken Hill and slowly moving east – have gone far beyond the proposed advisory body.

“I unashamedly agree with and support the amendment and the question but the sessions we are having are about providing a safe space to have a conversation.

“And we are trying to get people to come to these forums to ask the questions. And any question is valid. In fact the only silly question is the one you don’t ask because then you don’t get an answer,” Mr Scott said.

“People will sometimes step away and then step back in and ask you a question afterwards. But they generally ask.”

Mr Scott knows the phrase “safe space” causes some people to roll their eyes but he says that is exactly what this is. No judgment.

“You have to put people at ease. This shouldn’t be about badgering and bullying people,” he said.

“This is about changing the document which governs our nation. This is a serious document that deserves serious consideration and serious thought, not flippant, ridiculous misinformation.”

While the Yes and No sides of the campaign have each hosted forums in capital cities where most Australians live, the Uluru Dialogue has done most of its work in regional and remote communities. They are listening, talking and having one-on-one conversations with people. They have found a nation eager for facts.

Indigenous people often arrive with questions, too. Some arrive opposed to the voice because they believe the government would choose voice members for them if the referendum succeeded, although the principles agreed to so far by government include that communities would choose their own representatives.

“Most people get their information from social media,” Mr Scott said. “Sometimes the first question people ask is ‘Is it OK, can I ask this?’ And I say ‘If you don’t ask it, I’ve failed in what I am doing here. I’m not recording what you are saying.’

“They ask about race issues and say ‘I’ve heard you people get free loans and free cars’ and I say ‘Well no, that doesn’t happen, you can ask (Indigenous) people here’.”

Mr Scott said that in farming towns such as Moree in NSW, some locals have come to see the voice fulfilling a role like the Farmers Federation fulfils for them.

He said he wishes local governments across Australia would host information sessions about the voice like the ones the Uluru Dialogue offers almost daily.

There, people are free to talk about the failure of government to follow through, the wasted and misdirected billions in Indigenous affairs and the way forward.

“There are very few places in our culture and our society where these discussions are able to be had,” he said. “What I’m finding … is people are actually voicing their concerns about these very things.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout