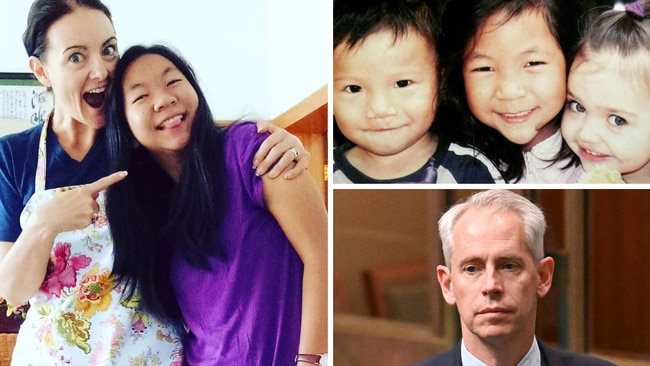

Alexandra Jagelman and Enji ‘Hope’ Su’s fight for Australian citizenship

A miracle baby saved from certain death by an Australian woman working in a remote corner of China has been denied Australian citizenship in the latest immigration farce under Andrew Giles.

A miracle baby saved from certain death by an Australian woman working in a remote corner of China has been denied Australian citizenship in the latest immigration farce under embattled minister Andrew Giles.

The Federal Court last week sided with Mr Giles when it ruled that Enji “Hope” Su should not be entitled to Australian citizenship. The court found that Enji’s adoptive mother, Alexandra Jagelman, was not her mother at the exact time of her birth and so the child could not be entitled to citizenship by descent.

While Mr Giles has been scrambling to undo the damage caused by his decision last year to make it easier for criminal non-citizens to remain in Australia through his ill-fated Direction 99 order, his department has in contrast doggedly resisted attempts by Enji and her family to secure her Australian citizenship.

The Administrative Appeals Tribunal late last year found – just as it did in similar cases involving Enji’s older siblings in 2020 and 2021 – that Enji should be entitled to citizenship. But unlike those earlier decisions, which the Coalition government opted not to challenge, Mr Giles chose to formally appeal against the AAT’s decision in the Federal Court.

The various court and tribunal decisions detail Enji’s incredible story of survival and the extraordinary devotion of Ms Jagelman to giving the girl an unlikely future.

Ms Jagelman had been working for a Christian NGO in the Upper Mekong region of China, bordering Myanmar and Thailand, for more than three years at the time Enji came into her life.

Ms Jagelman was walking home after work with her two small children when she was stopped by a colleague, who informed her a 15-year-old Lahu girl from a poor village had given birth via emergency caesarean to a child that appeared to have a brain injury.

The Lahu people believe that children born with deformities or disabilities are cursed. In a statement signed by Ms Jagelman in March 2022, she said she was told that the girl’s birth family wanted Ms Jagelman to confirm that the baby had problems “so they could decapitate it”.

“Still standing beside the road, the colleague shared the request by the birth parents to assess the baby and I immediately agreed to help,” she wrote. “However, I told him, ‘It can be very difficult to know the extent of brain damage in a newborn and if I do find that there are signs of brain damage, I would not allow them to kill the baby, I would take the baby, no matter the problem’.

“Upon hearing the threat to the baby’s life, I immediately decided I would raise her as my own daughter no matter the disabilities, in order to save her life.”

When Ms Jagelman arrived at the local hospital a short time later, she could see that the baby had a bulging fontanelle, substantial brain haemorrhaging, and was having constant seizures. No normal reflexes were observed when the hospital’s head pediatrician performed a newborn check, with the doctors confirming that the lack of normal signs were due to brain damage sustained during the obstructed labour.

“I spoke with the birth parents and confirmed what the pediatrician had said, that it was very likely that the baby had some brain damage although it was impossible to say what the extent would be,” Ms Jagelman would later write.

“They [the birth parents] immediately turned around and walked out of the hospital.”

Ms Jagelman agreed on the spot when asked by the pediatrician if she would take responsibility for the baby, telling the hospital she would pay for all medical expenses for the girl, including the emergency caesarean.

“I then asked for a bottle of milk formula and proceeded to sit on the hospital bed, and successfully fed her, despite her abnormal reflexes,” she wrote.

Today, more than two decades later, the extreme poor health of Enji’s early days are no more. The Federal Court described her as a “healthy vibrant young woman”.

But she has now been denied the Australian citizenship held by others in her family following last week’s Federal Court decision.

AAT member Louise Bygrave last November determined that Enji should be entitled to citizenship, finding that Ms Jagelman became the girl’s parent at the time she was born with substantial brain haemorrhaging and was expected to have significant disabilities.

“I simply cannot accept that ‘at the time of the birth’ is the precise moment in time on a particular day that a child is born. This interpretation would not allow for the various experiences of birth that occur in the ordinary sense of the word,” Dr Bygrave wrote.

She also said her decision was consistent with the procedural instruction issued to decision-makers by the Department of Home Affairs, which states that “to make a fair, reasonable and lawful decision, it may be appropriate to depart from the approved policy and procedures, depending on the facts of the particular case”.

The Federal Court, however, accepted the argument advanced on Mr Giles’ behalf by Nick Wood SC for the Australian Government Solicitor that the AAT had made a mistake when it made its decision. “The tribunal made an error of law in failing to accept that ‘at the time of the birth’ is the precise moment in time on a particular day that a child is born. In so doing, the tribunal failed to apply the well understood meaning of those words. The time of physical birth is not affected by wider social and cultural circumstances existing at that time,” Federal Court judges Michael Wheelahan, Elizabeth Cheeseman and Lisa Hespe wrote in their decision.

They said that the ordinary meaning of the phrase “time of birth” denotes the point from which a baby exists or starts life outside of his or her birth mother’s body, and did not extend to a period of hours after the events surrounding Enji’s birth.

“The application of that narrow time requirement to the facts of the present case is heartbreaking,” the Federal Court judges wrote.

“Ms Jagelman’s dedication and devotion to her daughter is unquestionable. The effect of that dedication and devotion on Ms Su was aptly described in submissions as miraculous. A child abandoned at birth because of diagnosed brain damage now lives as a healthy young woman.

“However, the pathways to Australian citizenship chosen by parliament are circumscribed by arbitrary lines. The fairness of those lines reflect the legislative policy choices made by parliament.”

The Federal Court judges also knocked back a request from Enji’s counsel for an order for costs, saying they were not persuaded “that there are any features of the case that warranted an order more favourable to Ms Su than that sought by the minister”.

The decision by the Immigration Minister to appeal the matter to Federal Court is all the more extraordinary given the precedents set by Enji’s older brothers. Those brothers had near-identical circumstances to those of Enji and also received favourable citizenship decisions from the AAT. However, neither of the respective immigration ministers of the time of those decisions, Alan Tudge and Alex Hawke, opted to challenge those outcomes in the Federal Court.

‘Ms Jagelman’s dedication and devotion to her daughter is unquestionable. The effect... was aptly described... as miraculous’

Since then, there has been a Full Court decision clarifying how the question of the time of birth should be interpreted.

In a statement to The Australian, a spokeswoman for Mr Giles said Enji’s case was “about time of birth”.

“The court found that time of birth meant at the time of an individual’s birth,” the spokeswoman said.

While the Jagelman family is still based primarily in Thailand and China, the family maintains strong ties to Australia and some of Enji’s siblings live, work and study here.

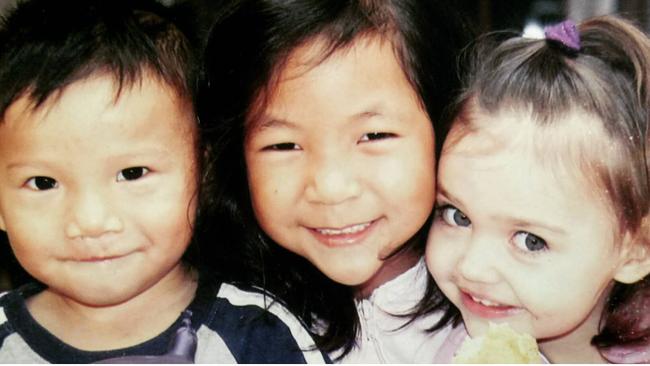

Enji’s older brother, Enli “Silas” Su, was born at a hospital in Yunnan province in 1998, and was abandoned by his biological parents shortly after his birth. Enli was born with a cleft lip and palate, and his Akha ethnic minority parents believed the deformity was a sign that the child was cursed.

Ms Jagelman was a healthcare worker at the hospital at the time, and grew increasingly concerned for the boy over the following days as it appeared he had not been fed by the hospital nurses. Three days after he was born, she approached the hospital’s director and offered to raise the boy as her child. Her request was approved, and she has been his parent ever since.

About 18 months later, Ms Jagelman received a call from a pediatrician informing her that another newborn boy had been abandoned by his biological parents due to his cleft lip and palate, and asking her if she would take the baby.

When she arrived to collect the child the next day, she was shocked to find the boy’s parents there with him. They thanked her for taking their son. Ms Jagelman, however, told the parents that she would show them how to feed the baby with a cleft feeding bottle and that she would organise free cleft surgery when the boy was five months old.

When she returned home the following day, the owner of the shop next door gave her a box that had been left for her. Inside the box was the baby, the cleft feeding bottle, the baby’s birth certificate and a note asking Ms Jagelman to raise the baby.

“Given that the boy has defects and that we have heard there is a foreigner who has an adopted baby with the same defects as our child who has grown very well, my wife and I are willing for this child to be adopted by the kind-hearted foreigner. We will never regret this decision and appreciate the foreigner,” the note read.

Ms Jagelman was later told that the baby’s parents had said that their relatives would kill the baby as soon as they saw him, and that they did not even have the money for the bus fare to get the child to the free cleft surgery.

She named the child Enci, meaning grace and kindness. He also goes by the name of Josiah, and in 2021 – the year in which the AAT determined he should be entitled to Australian citizenship – was in the final year of a bachelor of (mechatronic) engineering honours degree at the University of Sydney.

“He has a ‘passion for working and building biomedical devices’ that has been inspired by watching his mother, Ms Jagelman, help people in the medical field,” Dr Bygrave noted at the time of her decision.

Ms Jagelman appears to have also adopted a fourth child in similar circumstances, with her Facebook page showing photographs of a boy younger than Enji.

“He has brought us such joy and delight since the day we got him, starved, covered in ant bites and almost dead. He started smiling at five days old and has been smiling ever since,” Ms Jagelman wrote on her social media page.

Ms Jagelman, through her lawyer, declined to talk to The Australian.

She continues to work in the Upper Mekong alongside her husband, who works in the coffee industry. According to her Facebook page, Ms Jagelman is employed by Samaritan’s Purse International Relief, a non-profit Christian organisation that aims to provide emergency relief and development assistance to suffering people around the world.

She is also the founder of the Mekong Hope Surgical Fund, which raises money to help poor patients and their families access medical treatment.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout