Higgins’s complaints outside court that her life has been publicly scrutinised for the world to see needs to be tested against the fact that she abandoned her right to remain anonymous. Her rights are set down in the Evidence Act that applies in the ACT. Under ACT law, Higgins could have given evidence in a remote witness room. She chose to give evidence in open court. Indeed an application must be made to give evidence in court in these proceedings. Higgins could have maintained her anonymity because the law prohibits the publication of a complainant’s name.

Higgins did not wish to hide her identity. She chose an open court. She chose scrutiny when she aired her allegations that she “woke up mid-rape” in a ministerial office on March 23, 2019, before making a formal complaint to police.

Once she did that, an unstoppable #MeToo media juggernaut was set in one direction, for Higgins. Responsible media will objectively and carefully report criminal charges within the law. Irresponsible media, including the wild west of social media, used Higgins’s decision to go to the media before the police to junk values at the heart of our criminal justice system.

From that moment, a fair trial for the defendant appeared to be a lottery, not a guarantee.

Thursday’s mistrial is a fitting end to the media trial that preceded court proceedings. How could anyone expect a jury to be free from the enveloping, swirling, at times wild media forces, especially on social media, that applauded Higgins’s story, commended her bravery, celebrated her credibility and simultaneously ran untested stories about Bruce Lehrmann?

When the sections of the pro-Higgins media use a rape allegation to justify campaign journalism, wouldn’t a jury member do some research on the side? A jury is made up of human beings, not automatons.

Outside the courtroom, a young, clearly emotional woman, untrained in the law, expressed her distaste that an accused has a right to silence. But that, along with the rule of law, the presumption of innocence and due process, forms the foundation of our criminal justice system.

Higgins was upset that she was examined in court. Alas, that is a critical element of our legal system, too. Lawyers call cross-examination the truth engine of the law for good reason. No claim of wrongdoing is worth anything unless it is the subject of cross-examination.

In this case, many of Higgins’s most critical allegations were revealed as inaccurate or untrue. There were inconsistencies in some of Lehrmann’s claims too.

The difference is that the accused does not bear the burden of proof. He is presumed innocent until proven guilty beyond reasonable doubt by a court that has considered the evidence.

J’Accuse is not the perfect fit here. But the 1898 letter by Emile Zola condemning institutional injustices meted out to Alfred Dreyfus is still a compelling historical reference for what happened to Lehrmann. J’Accuse will do just fine to capture the modern institutional failures that coalesced to turn the presumption of innocence into the presumption of guilt.

The media persecution of Lehrmann should never have happened. It happened because so many people in positions of power chose to ignore fundamental values in a fair society. Many, including high-profile journalists and celebrities, used their traditional media platforms and their social media streams to become #Me-Too combatants. They turned their backs on the presumption of innocence until proven guilty beyond reasonable doubt before a criminal court. Many worked from the presumption of guilt. They were not interested in carefully and methodically testing allegations in the search for truth.

Higgins gave evidence that she did not think the matter would end up in court. “I thought I’d go back to uni and disappear,” she said. But when Higgins chose the media to air her rape allegation, she became the vessel for those who wanted to use her allegation to further their careers, preen in public, prosecute the culture at Parliament House in general and the Morrison government in particular. Some of our most celebrated journalists became crusading activists for Higgins. They housed her, and comforted her, advised and counselled her as they whipped up a media trial untethered from the guardrails of justice that presume innocence and provide due process. In his closing remarks, before the mistrial, DPP Shane Drumgold insisted this trial was simply about what happened on a couch in a room on March 23, 2019. That statement does not stand up to scrutiny if you have turned on a TV or radio or read a newspaper or scrolled through social media for the past year or so.

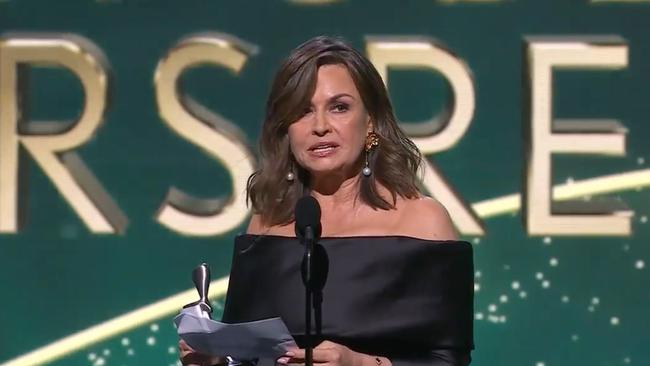

Lisa Wilkinson’s speech at the Logies, and commentary around it afterwards, forced this trial to be delayed. As McCallum said at the time: “The implicit premise of (Wilkinson’s speech) is to celebrate the truthfulness of the story she exposed.”

Indeed, many in the media are guilty, as McCallum said, of obliterating the critical distinction between an allegation and a finding of guilt. After this trial, they stand condemned for their ill-conceived activism and shoddy journalism. The legal system is not off the hook. Those who interfere with the administration of justice should be prosecuted. When there is no line in the sand, the right to a fair trial becomes meaningless.

J’Accuse reflects other institutions that treated an untested allegation as a reason to promote Higgins in all manner of ways. The National Press Club offered its televised platform to Higgins, who had made untested allegations, alongside Grace Tame, whose allegations of abuse had been tested and confirmed by a court of law. As McCallum said when deciding to delay the trial, this blurs the important distinction between an untested allegation and a finding of guilt by the justice system.

Marie Claire magazine crowned Higgins and Tame as Women of the Year on the front cover of its November edition last year. Pro-Higgins journalists reported it as news. It points to sustained levels of institutional activism that sidelined the presumption of innocence, due process and a fair trial in favour of a partisan campaigning.

Higgins was made a visiting fellow at the Australian National University’s new Global Institute for Women’s Leadership. When Higgins was appointed, Julie Gillard lauded her as an “incredible leader” and “a powerful force for change who had already greatly advanced the national conversation”. How so? By making allegations that had yet to be tested in court, let alone by a fair-minded media?

Add in the $325,000 reported deal stitched up with Penguin Random House, where Higgins was given a hefty advance to turn her claim into a book. A successful book would obviously hinge on a guilty verdict. Higgins admitted in court that she had drawn up chapter headings before she had a formal interview with police.

J’Accuse captures how Lehrmann was told by a legal aid public defender who, at one stage, acted for him, that Higgins’s credibility should not be robustly tested in court, that at most the defence might suggest she was “mistaken”.

Is this reluctance to test evidence standard practice among public defenders? If so, they are not doing their job.

J’Accuse reflects how prime minister Scott Morrison joined these same forces working against a fair trial. He stood in parliament and apologised directly to Higgins, for as yet untested claims, and without knowing anything about the quality of evidence to support those claims.

There are other political names who used Higgins as a vessel to seek revenge on the Morrison government. Each of these culpable combatants should pause and ask themselves this: if they were in the dock, if their son or father or brother were in the dock, would they behave in the same way?

After this aborted trial, and what preceded it, many of our most important and influential institutions stand at a crossroads about their reporting and prosecution of sexual abuse cases. Will they continue down a path that is recklessly or deliberately dangerous to the rule of law and a fair trial? Or will individual institutions learn from this? Will they, even quietly, recognise the gravity of their professional misjudgments?

In The Queen v Lee, a unanimous High Court noted in 2014: “Our system of criminal justice reflects a balance struck between the power of the state to prosecute and the position of an individual who stands accused.”

The pro-Higgins forces tainted by this mistrial should reflect on how their behaviour and their decisions have up-ended this delicate balance. A new trial ultimately will determine whether Lehrmann is guilty or innocent, but the way some in the media have used Higgins and assumed Lehrmann’s guilt is just wrong. The damage done to two young people is incalculable and unforgivable. The damage done to our society even more so. J’Accuse indeed.

The press conference by Brittany Higgins after Chief Justice Lucy McCallum declared a mistrial points to a legal system in capitulation to forces that do not respect the rule of law, a justice system cowering in the face of trial by media. This trial ended, fittingly, as it began, in the media. Therefore, no one should be surprised that the jury was discharged in the ACT Supreme Court on Thursday morning, with McCallum declaring a mistrial after material was found in the jury room that was prejudicial to a fair trial.