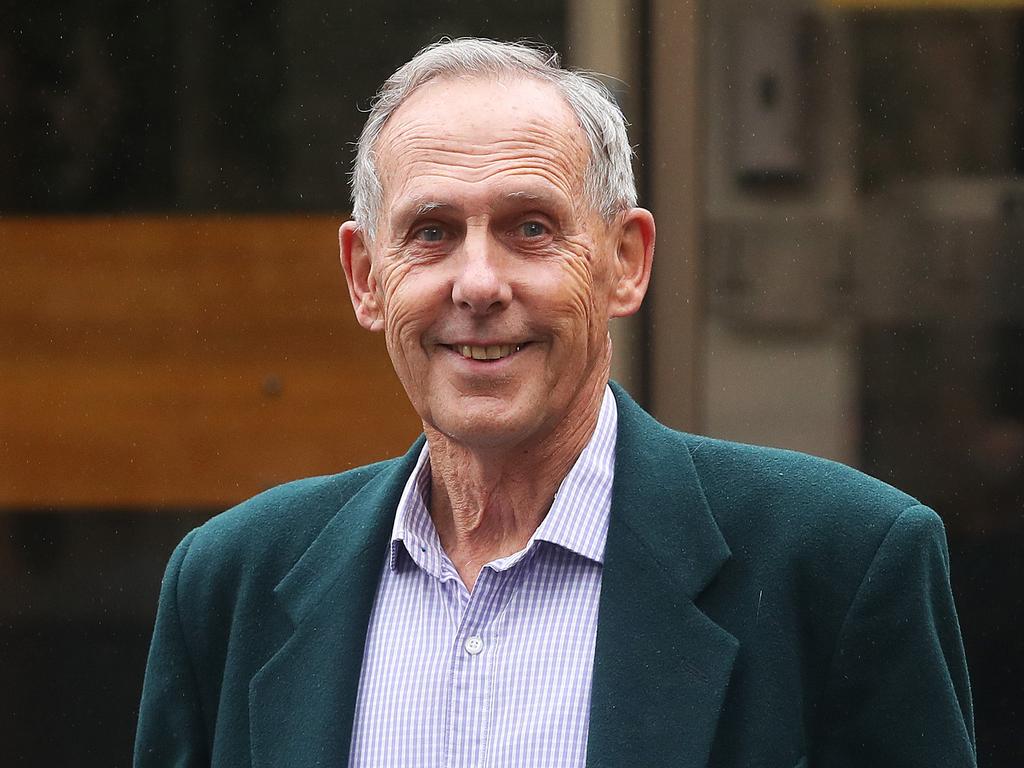

50 years after his thylacine expeditions, Bob Brown says tigers are gone – and science should leave it that way

Fifty years after moving to Tasmania to find the thylacine, Bob Brown wants the world to finally accept it is extinct – and should not be genetically engineered back to life, as scientists plan.

Fifty years after moving to Tasmania to find the thylacine, Bob Brown wants the world to finally accept it is extinct – and should not be genetically engineered back to life, as scientists plan.

The veteran conservationist spent part of the early 1970s traipsing through remote Tasmanian forests, carting buckets of blood and caged chooks, to lure a Tassie tiger into the open.

Dr Brown, then a young Sydney doctor, in 1972 joined what had been a two-man Thylacine Expeditionary Research Team, following up 250 sightings, particularly in Tasmania’s remote West.

Despite funding from British Tobacco and a local newspaper, the team found nothing, sometimes with comical results.

“I was able to discount all but four of those 250 sightings,” Dr Brown recalls. “For example, I went to the West Coast where there’d been a sighting in the sand dunes by a young fella out hunting.

“Two days later when we got there, out came a Ferguson Tractor along the beach, out of nowhere, with loping along beside it an Irish wolfhound. Everybody went silent.”

Another involved a West Coast fisherman who claimed to have killed a thylacine and locked it in a hut, only for it to disappear, leaving just hair as evidence.

“While the CIB in Hobart had said they were thylacine hairs, I got those hairs and sent them to the Turnbull Institute in Melbourne – they said they were definitely not thylacine,” he said. “Time and time again, the hype around tiger sightings was found to be false.”

The most recent semi-credible, documented sighting was announced in 2016, when two bushmen and a thylacine hunter claimed to have secured “the first verified footage” of a thylacine since 1933. Wildlife expert Nick Mooney assessed the probability of the images being a thylacine as one-in-three.

In March last year, a team of international researchers, assessing observation records from 1910 onwards, found the species may have survived as late as the early 2000s, with “a very small chance that it still persists in the remote South West”.

Dr Brown, tiger hunter-turned-environmentalist and Greens politician, is unconvinced, believing he discovered the terrible truth back in the bush in the early 1970s.

“There is nothing I wish more that I’m wrong about – it would be fantastic to find a tiger,” he said.

“(But) no, the thylacine is the only creature I know of that was deliberately ‘extirpated’ by democratic lawmakers. It’s as dead as the dodo.”

Some, however, believe it’s only a matter of time before the dodo, the thylacine and the woolly mammoth – or creatures resembling them – are resurrected by science.

One collaboration hoping to do just that for the thylacine involves University of Melbourne geneticist Andrew Pask and US genetic engineering firm Colossal Biosciences. It aims to produce “the best quality genome possible”, using gene editing based on related species to fill gaps in tiger DNA.

Stem cell and assisted reproduction techniques would then transform a thylacine-like cell into a living creature, via a surrogate and/or artificial pouch, for eventual return to the wild.

Dr Brown is unconvinced, describing the multimillion-dollar research as “a dilettante pursuit”. “Those who are pursuing it have lost the plot, in terms of our need to save the thousands of species we are currently driving to extinction,” he said.

The last known thylacine, or Thylacinus cynocephalus, died in Hobart’s Beaumaris Zoo in 1936.

The species is officially presumed extinct.

Professor Pask and Colossal did not respond by deadline.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout