Boxing Day tsunami, 20 years on: the miraculous triumph of human endurance

In the aftermath of the 2004 tsunami, one of the most destructive natural disasters in recorded history, reconstructing Banda Aceh was not just about replacing a flattened city but repopulating families and communities after one-third of its people perished.

This is how a community rebuilds after a catastrophe – slowly, painfully and from the tsunami-sodden ground up.

In the aftermath of the 2004 Boxing Day tsunami, one of the most destructive natural disasters in recorded history, the reconstruction of Banda Aceh was not just about replacing a flattened city but repopulating whole families and communities after one-third of the city’s people perished.

Rebuilding structures is one thing. Finding strength to start again after losing wives, husbands, children, parents, friends and relatives takes a special fortitude.

The tsunami crushed whole swaths of Aceh province, a jewel of Indonesia at the northwestern tip of Sumatra, but also devastated Southeast Asia. Some 228,000 people perished that day across 14 countries. Of those, more than 170,000 died in Aceh.

“The blessing of the tsunami” is a phrase repeated over and again across this deeply religious province that bore the brunt of the disaster.

The Australian travelled to Banda Aceh and discovered common threads binding those at the heart of the disaster, those who led the recovery and those living with the legacy of that day.

From Indonesia’s then vice-president who led an emergency response that became a global template, to the Aceh insurgents who laid down their weapons, the dancer who picked up the dead, and the miracle boy in the Portugal football jumper found 21 days later, the prevailing sentiment is still one of gratitude.

There is also pride that in its darkest hour, the community did not descend into chaos but pulled together in a tradition known across this remarkable archipelago as gotong royong, or “mutual assistance”. Every story is a small triumph of human endurance.

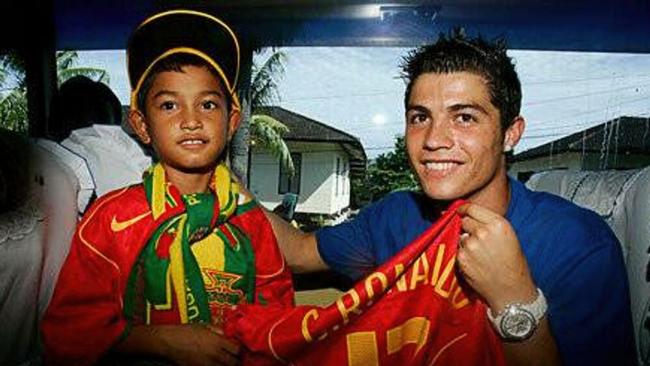

Among the most famous is that of the Lost Boy of Aceh, a seven-year-old soccer fanatic named Martunis Sarbini who was swept out to sea in a red and green Portugal team jersey and found three weeks later roaming a mangrove beach in search of food.

His miraculous survival tale was broadcast across the globe, including in Portugal where a rising football star, Cristiano Ronaldo, read it as a divine sign and flew the boy and his father over five months later.

They took him to tourist attractions, to a football match, and to play with children untouched by tragedy. Pictures of the little boy with the storied footballer and his team mates line the walls of his now-remarried father’s home, rebuilt on a grander scale thanks to contributions from the European football club and the Indonesian government.

It took 20 years to find the words to tell the magic realism-tinged story he does today; of watching his mother and sisters pulled beneath the waves, of hearing houses crack and break, then slipping into blackness only to wake up floating out to sea on a bed stocked with packets of biscuits and instant noodles.

“I don’t know how I got there,” he insists. “I could hear a lot of people calling for help and many trying to save themselves. I saw lots of bodies and debris.”

Soon the bed would sink and he would climb on to a floating tree trunk. He would see a toddler struggling in the water, a small arm waving amid the debris, and try in vain to grab his hand.

Was it days or hours later the waves returned him to land, to dense mangroves littered with bodies and debris?

He would stay there three weeks, sifting through rafts of detritus for food, collecting rain water in an upturned fridge, sleeping on a bed lodged on mangrove roots with the bodies of tsunami victims floating in the dark water beneath.

“All I could see was emptiness,” he recalls. “There were no big trees, just mangrove roots. I couldn’t hear anything, I couldn’t smell anything even though there were bodies everywhere – headless bodies, armless bodies, sometimes faceless, some completely black.

“My only friends were the corpses.”

Martunis can’t explain why he didn’t try to leave except to say he “felt comfortable there … I had food. All I did was sleep, look for food, and pray for my family”.

Then one day he woke to the sound of voices. Soon, two local men were pulling him across the fetid, watery graveyard on a polystyrene box. They gave him food and drink, then handed him to a team of British journalists.

The story of his discovery, broadcast in Indonesia and around the world, would reunite Martunis with his father and grandmother, his only surviving relatives, and bring the motherless boy opportunities he could never have imagined.

Now 27, with a wife and small daughter of his own, he marvels at what came next. “I was still so sad because I had lost my Mum, my family and my house and I felt like they treated me like family,” he says of the Portugal national team and its star footballer.

Ronaldo helped finance his education and, later, a year in a Lisbon football academy, though injuries would cruel the young man’s chances of going professional.

That thwarted fairytale ending torments and drives him, as though his own survival is not remarkable enough.

He creates daily life vlogs for his online following but has the air of someone still cast adrift, searching for higher purpose.

“In a way you could say the tsunami was a blessing,” Martunis insists, repeating the Aceh mantra when we meet. “I lost my mother, and I still miss her today. But I was able to meet Ronaldo, to travel the world and have my story known by the world.”

He still has the little red and green soccer top he wore when he was found, along with piles of newspaper clippings of his post-tsunami experiences.

In recent months, he has tried to reconnect with Ronaldo but has been told the footballer is about to retire and that he should wait.

He can’t be sure he will ever see him again.

The response

As Indonesia’s new vice-president – inaugurated just two months earlier alongside president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono – it fell to Jusuf Kalla to lead the initial post-tsunami emergency phase in Aceh that has since become a global template for early disaster response.

The now 82-year-old remembers opening the rice warehouses, clearing neighbouring Medan out of bread, instructing the housing minister to buy up every tent in Jakarta, and ordering trucks by the hundreds from Sumatra to move into Aceh to distribute aid and collect bodies.

“Every minute, I was making quick decisions,” he told The Australian ahead of the 20 year anniversary. “People were asking me how to manage the bodies. I wanted to consult an ulema (religious scholar) but there was no one because they were also victims, so I issued the fatwa myself that all bodies could be buried in one, big mass grave.”

It was not an easy call for the devout Muslim, given Islamic burial rites require all bodies to be washed and shrouded.

“It weighed on my conscience but it would have been more dangerous if we had not buried the thousands of bodies. We feared the disease that could spread,” he says.

The full scale of the disaster became clear only when Kalla flew low over Aceh in an air force plane, and the veteran politician burst into tears.

It was then he made the critical decision to declare Aceh open to outsiders.

Kalla brought a Metro TV team into the stricken province, enabling the world to see the first devastating images of the catastrophe, opening the floodgates to billions of dollars in aid.

News had emerged fast from Thailand, where more than 5000 people had died – many of them foreign tourists – and from southern India and Sri Lanka, which suffered a combined death toll of 46,000.

But Aceh was only just emerging from a brutal military emergency rule in which it had been largely closed to outsiders. It was still under strict curfew and in the midst of an ongoing separatist insurgency when the tsunami hit.

“I wanted people to know we were open for all support. But I knew if Aceh was to recover, it had to have peace,” Kalla says.

“That was critical for rehabilitation and reconstruction.

“We couldn’t do that if the fighting continued.”

Kalla had overseen negotiations before the tsunami but both sides were dug in. The Free Aceh Movement (GAM) wanted independence which the Indonesian state would never give.

He gave himself until July 2005 to end the conflict. On July 15, negotiations were concluded and the next month representatives from both sides flew to Finland to sign the Helsinki memorandum of understanding.

The agreement set out a new political relationship between Aceh and the Indonesian state, including provisions for local political parties, the rule of law, and a fairer resource royalty split, as well as for the disarmament of GAM and reintegration into society.

Contrary to popular belief, it made no mention of sharia law, the strict Islamic penal code imposed in Aceh that has since earned the province notoriety for the public Friday whippings for crimes such as adultery, homosexuality and gambling that have stymied its progress.

Kalla says he didn’t see the need for sharia in Aceh, an already deeply religious province, and it had been offered to the Acehnese long before the tsunami by former president Abdurrahman Wahid as an alternative to independence.

The single most important lesson Indonesia learned from the disaster was to work fast, and make quick decisions, he says.

Australian prime minister John Howard’s similarly quick action, first by sending in the country’s biggest peacetime military deployment, and then by pledging $1bn in bilateral aid during the January 9 emergency leaders’ summit in Jakarta, was also critical.

ANU Indonesia expert Edward Aspinall says those actions marked a “historic breakthrough” that ended a troubled period in the relationship after Canberra had backed East Timor’s independence bid.

“It was something … really appreciated both at the central government level and on the ground in Aceh,” he said. “I remember going to Aceh soon after the tsunami and the Australian military had a very visible presence.”

Kalla agrees Canberra’s response improved the relationship “because Australia was one of the first to come in”.

Within three years, 140,000 homes and public buildings had been rebuilt under the watch of the Rehabilitation and Reconstruction Agency for Aceh and Nias that Kalla established, with an anti-corruption agency alongside tasked to oversee its spending and regular international audits.

As for so many who witnessed Aceh’s devastation, the experience was life-changing for the three-time vice-president, who adopted a 14-year-old Acehnese boy, Muhammad Haikal, his wife had met in a post-tsunami hospital ward.

Haikal is now an emergency doctor in Makassar and holidays every year with his adopted family.

Picking up the dead

One, two, three, throw; one, two, three, throw.

Some days the rhythm was all that made sense to Murtala, a 25-year-old dance student, who had rushed back to Banda Aceh after the 2004 Boxing Day tsunami in a bus full of volunteers and food, only to find himself picking through the apocalypse for bodies.

On the first day he had recited long prayers for the dead. By the third day, it was a hasty “Bismillah” (in the name of God).

By the end of that first week, Murtala’s world had been reduced to a macabre and godless waltz; One, two, three, throw; one, two, three, throw.

Women, men, children, babies … one after another bagged and heaved on to what was left of Aceh’s roadsides for collection and mass burial by Indonesian, and sometimes Australian, military.

“Everyone lost everyone in Aceh but my family survived,” he recalls from the NSW’s mid-coast, where he now lives and runs the Suara Dance Company with his Indonesian-Australian wife and fellow dancer Alfira O’Sullivan.

“I thought, maybe this is why God saved all my family. Maybe he was saying ‘This is your job, man’. We would find bodies under roofs, under rubble … everywhere.”

On a good day, with easy access, he and his two brothers might recover 50 dead.

Sometimes there would be signs pointing to a body, scrawled in haste and hope that someone would provide the proper burial that those who fled could not.

Within weeks, Murtala no longer needed the help. He could determine the location and number of cadavers just by the smell, even as the scale of the tragedy was slowly dulling his sensitivities.

After three months, when only bones were left to find and the government announced an end to the search, Murtala turned back to the living and began teaching Acehnese dance to kids in displacement camps.

The program brought joy to a traumatised population and it wasn’t long before an international charity – one of the many struggling to spend billions in aid that poured into Aceh – offered to fund a larger version of it.

The catch was he had to set up an NGO. And so TALOE, a rare Acehnese-run charity in a sea of foreign aid groups, was born.

Murtala hired tsunami victims to help teach, urging them to think of the work as therapy for themselves as much as for the 3000 children they would eventually reach.

The key to its healing powers was the physical closeness traditional Acehnese dance demands, and the knowledge of land and sea passed down through ancestral songs with the warnings that so many had failed to heed.

“You feel together. When you ask someone ‘How are you?’ and you’re sitting 30cm apart, it’s a big feeling. It wasn’t just the kids dancing that felt it, but the parents and adults watching the kids,” he recalls.

“You would hear them say things like ‘If his mother was still alive she would be so proud’.”

A program that started in the camps migrated with the people as they returned to rebuild their flattened homes and lives.

Yet with the money came a new set of problems.

For Murtala, the “real tsunami” was the waves of cash that flowed into Aceh in the wake of the catastrophe and corrupted gotong royong, the tradition that knitted the community together. “I didn’t lose as many friends in the actual tsunami as I did when the money came rolling in,” he says. “Everyone had too much money.”

TALOE achieved much with the three rounds of funding it received but by the time a young O’Sullivan came knocking at his Banda Aceh office in early 2006 looking to volunteer, he was done with aid culture and seeking a way out.

“I said to her ‘If you want to learn traditional Acehnese dancing, I don’t have time to teach you but you could come to the refugee camp with me and learn it with the kids’. The next day she came along and it was like we were soulmates.”

Suara Dance Company debuts Bunyi Bunyi Bumi (Sounds of the Earth), a new dance work drawing on Murtala’s post-tsunami experiences and those of Australia’s First Nations people, at Melbourne’s AsiaTOPA arts festival on February 20-23.

In from the cold

Kamaruddin Abubakar was a 37-year-old separatist fighter with the Free Aceh Movement, based in the mountains above Banda Aceh, when the earthquake that triggered the biggest tsunami on record hit more than 100km away.

The force of the magnitude-9.2 tremblor was so great that in the insurgents’ forest hide-out, it sent giant, brittle trees cracking and falling around them though none of them had any idea it had also triggered a tsunami.

Kamaruddin tried to call his wife, who lived in Banda Aceh with their four young children, but all lines were down. It would be days before he learned they had perished in the waves.

After years of fighting the Indonesian state for independence, “suddenly, God willed otherwise, and within 10 minutes the tsunami claimed more than 170,000 Acehnese lives”, he told The Australian.

It was a “turning point that softened both sides”. After struggling for years to find common ground, the tsunami unified the warring sides in grief.

Both realised without a ceasefire, no foreign aid could come. Six months later the conflict was over.

“It became clear that continuing the war was unsustainable,” says Kamaruddin. “Starting in January 2005, we held several meetings, and by August, the MOU was signed in Helsinki, bringing peace.”

The agreement cleared the way for GAM to enter politics and for 70 per cent of the income from Aceh’s natural resources to stay in Aceh.

By December 2005, GAM had publicly destroyed its weapons and the Indonesian military was leaving Banda Aceh and returning to barracks.

“That’s something we are grateful for. Even though the situation was difficult, by God’s grace, it brought about change,” says Kamaruddin. “Looking back, we can see how things have progressed.

“I was involved in the peace process and through faith and acceptance of this trial from God, things have improved.”

Like thousands of fellow GAM fighters, a widowed and grieving Kamaruddin came down from the hills in late 2005 and rejoined civilian society, moving quickly into politics along with many of his insurgent commanders.

By 2006, GAM was fielding independent candidates in local elections and a year later former fighter Irwandi Yusuf was elected Aceh governor, unseating Azwar Abubakar, the man who had seen the stricken province through its darkest times.

Now remarried with two high school-aged children, Kamaruddin ran the campaign that led to last month’s election of former GAM insurgent Muzakir Manaf as Aceh’s next governor.

Muzakir, a Libyan-trained ex-commander, has vowed to complete implementation of the Helsinki pact, including the return of all combatants’ land seized by the state, hold a truth and reconciliation commission, and renegotiate oil and gas royalties with Jakarta.

Back from the dead

Twenty years ago, it was feared the village of Deah Glumpang would never recover from the tsunami that reduced its population from more than 1300 to 100 in a matter of hours.

The Banda Aceh fishing community less than 1km from the coastline was one of the worst-hit by the disaster, in part because so many people ran towards the water as it receded instead of away from it. “That happened because we didn’t understand what a tsunami was, or what to do,” says Munzir, a council elder for Deah Glumpang, which was last month declared a UNESCO Tsunami Ready Community.

To qualify, it had to prove it was fully prepared for another catastrophe, with plans in place, strong public education and an evacuation route to a five-storey evacuation building nearby.

The community is proud of its new certification and hopes to use it to lure international tourists who still flock to Banda Aceh to see its “dark tourism” attractions; the museum, the mass graves, and a mammoth power-generating barge washed 5km inland.

“We were different from people on Simeulue Island who knew to run from the waves because their ancestors had passed on a better understanding of tsunami. Now we want to share what we have learned,” says Munzir.

“We don’t want others to experience what we went through because for months our tears never ran dry.”

In the post-tsunami recovery, Australia rebuilt Deah Glumpang’s roads, Oxfam its homes, and the Japanese government an evacuation centre that hundreds of residents scaled last month in a tsunami drill that was the last hurdle to certification.

But the community had its own work to do.

“We didn’t just lose houses. We lost families, and so we had to rebuild those too,” he says.

“We experienced such huge loss that when we got married, it felt like we were healing ourselves a little. Especially when we had children. It helped our wounds a little.”

Deah Glumpang’s Tsunami Awareness co-ordinater Ema Iystiana’s now husband Mahyuddin survived being swept out to sea by the waves that claimed almost his entire family. He was one of the first to return to the village just days after the disaster.

“It was traumatic but he loves this village. And there was nothing left to lose,” she says.

Before the tsunami, Mahyuddin had lived with his extended family and saw no need to marry or have children of his own.

“But he lost so many of his family he needed a friend and so he married me in 2006,” says Ema.

Many Acehnese clung for months, even years, to the hope that their missing families had been swept along the coast. Perhaps they had lost their memories, or were being treated in the US hospital ship that anchored off Banda Aceh soon after the disaster.

Then with gradual acceptance came the will to rebuild. Aceh’s post-tsunami baby boom has been well documented and Deah Glumpang was no exception.

Two decades on from the tsunami, its youth-heavy population stands at 1414.

Where are you, De’Na?

In the intense national outpouring that followed the tsunami, one of Indonesia’s most beloved dramatists wrote an ode to a young actress and social worker, Mahdalena, whom he’d met in Banda Aceh months earlier and feared had perished in the waves.

Willibrordus Surendra Broto Narendra – Rendra as he was known – read his poem Di Mana Kamu De’Na (Where are You, De’Na) on national radio three days after the catastrophe.

It would be more than a week later that Mahdalena, known as De’Na to friends and family, would learn of the poem written in her honour, so immersed was she in a makeshift refugee camp where she had ended up after the tsunami swallowed her family home and the beloved grandmother who raised her.

The 29-year-old had given her a “very tight hug” the previous evening – the last time she would see her – before heading off to spend the night at the city’s Taman Budaya cultural precinct.

The first wave had already washed over the city by the time she was speeding away from the coast on her motorbike, past the Hotel Medan where a fishing boat had been swept into its carpark.

“I remember thinking if a boat could get swept 1.5km from the coast, this must be huge,” she told The Australian.

Worse was to come.

What at first had looked like smoke on the horizon was a wall of foam from a huge wave bearing down on Banda Aceh, one she would have to out run.

“Everything was chaos, everyone was out for themselves. I saw a military car hit and run over some people in the panic,” she recalls.

“I was in such a dilemma because my grandmother was at home but it was all about survival.”

She remembers the gridlocked crowds, and crossing the city’s Surabaya Bridge as it collapsed behind her, sending people plummeting into the river below.

In a field outside a mosque, she helped trainee doctors give first aid to the injured.

“People were lying everywhere, dead bodies also. I was knocking on people’s houses for supplies and sheets to cover the dead. Some were willing, some were not.”

So many of the dead had been stripped naked by the force of the waves, including Haj pilgrims who still had their IDs around their necks but no clothes.

The indignity was unbearable.

That night, she heard trucks in the area and assumed aid was coming. Instead it was looters, loading motorbikes on to trucks, plucking jewellery from bodies.

“Many people wanted to go check on their houses but there was always someone yelling ‘The water is rising, water is rising’ while behind them there were people looting.”

Those first chaotic weeks she would fend off people trawling the camps for orphaned children to adopt. She would work with UNICEF for months before returning to acting.

The poet Rendra would later introduce Mahdalena to Acehnese theatre director Mustika Permana. “It took the tsunami for me to meet the right person,” she says with a smile at the man she married and with whom she has a daughter, now 16.

Together they produced a docu-drama about the tsunami, and lived happily in a little replacement house made of concrete, built with aid money to withstand another disaster on the land where her grandmother’s airy wooden home had stood before the waves took it.

Mustika survived the tsunami but not the pandemic. He died in 2021, 11 years after the Rendra passed away, leaving Mahdalena with the lifelong burden of living up to his famous poem.

“For me, it was an honour but also a huge responsibility,” she says. “Most people who have poems written about them are already dead, but I am still alive.”

Additional reporting: Dian Septiari

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout