$1bn “golden ticket” visa scheme to be axed over concerns its gives criminals a pathway to citizenship

The $1 billion a year “golden ticket” visa scheme will be axed following concern it has given criminals a pathway to Australian citizenship without proper checks.

The $1bn-a-year “golden ticket” visa scheme will be axed following concern it has given criminals a pathway to Australian citizenship without proper checks and growing evidence the program has a profoundly negative impact on the economy.

The move follows revelations by The Australian that while more than 7000 Chinese citizens have been granted the $5m Significant Investor Visas, not a single applicant in the past 10 years has been rejected under the character test designed to help exclude criminals or those with suspiciously obtained wealth.

The scheme is expected to be killed off within the next year as the government pivots sharply to give priority to skilled worker visas, a move that will cause serious ructions in the multibillion-dollar business investment visa industry, where financial advisers, migration agents, banks and specialist investment firms have reaped huge rewards for a decade.

The government signalled a move away from business investment visas at the Job Summit, with the number of visas in the program halved for this year, in part because the enormous backlog of applications was thwarting attempts to process visas for desperately needed skilled workers.

On Sunday, Home Affairs Minister Clare O’Neil said the significant investor visa scheme was “a really big problem” in the immigration system.

“I think most Australians would be pretty offended by the idea that we’ve got a visa category here where effectively you can buy your way into the country,” Ms O’Neil told Sky News.

“I don’t see a lot of great benefits to the country currently … some really important journalism has pointed out that there are some potential security issues here in this visa.”

Figures obtained by The Australian show 2370 super-rich Chinese nationals have been granted primary visas, along with more than 5000 family members, under the Significant Investor Visa scheme, which requires a minimum investment in Australia of $5m and confers an automatic right of permanent residence.

None of those who applied has failed the “character test” since the scheme was introduced in 2012, and just 23 were refused for failing to provide accurate information.

Investors can gain citizenship even if they spend only 40 days a year in Australia and unlike other visa holders, they are not required to learn or speak English. There is also no upper age limit.

Australian Treasury calculations suggest a business investment visa holder will cost Australian taxpayers $120,000 more in public services than they pay in taxes over their lifetimes.

“The lifetime impact on the Australian budget is negative because these are people who generally are coming in at quite a late stage of their life, often at the end of their business career, and are coming to Australia basically to settle down and retire,” Ms O’Neil said.

“It is a visa program that I think isn’t adding value to the country and it’s something we will be looking at in the context of the review of the immigration program I have just announced. At the moment, I can’t see a lot of reasons to maintain it as part of our program.”

As governments around the world shut down passports-for-sale schemes in a bid to stop organised crime syndicates and corrupt regime officials hiding their loot, police and security agencies fear Australia has become the go-to destination for those with big enough wallets.

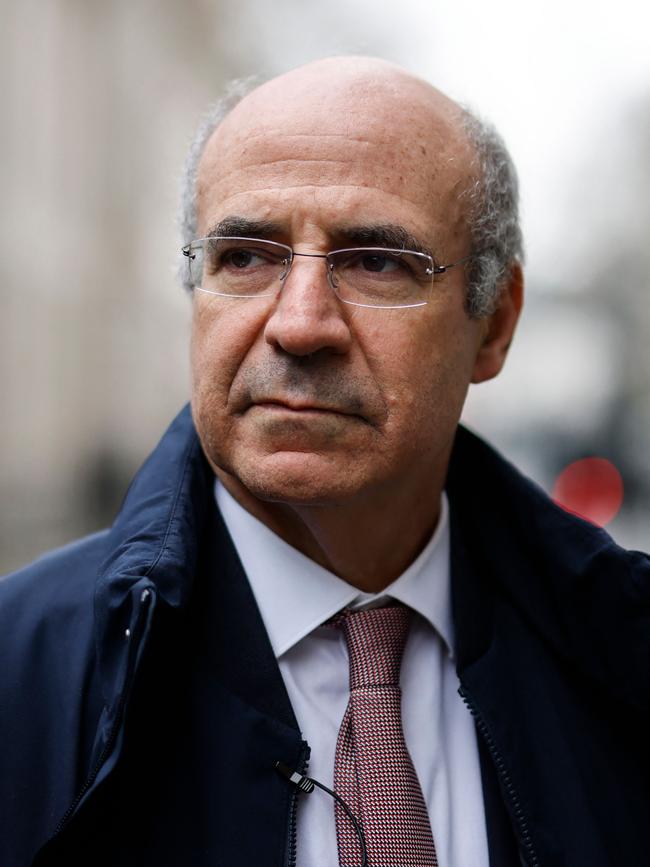

US-born British hedge fund manager Bill Browder, architect of the global Magnitksy laws that target corrupt officials and their wealth, said Australia risked becoming a pariah among nations that value the rule of law. “These schemes should be shut down across the world because the vast majority of people who are involved in them are the people you least want to have … settle in your country,” he told The Australian.

Super-rich members of Cambodia’s corrupt Hun Sen regime are also alleged to have bought their way into Australia through the scheme, with at least 80 of the visas granted to Cambodian nationals over the past decade, figures obtained by The Australian reveal.

Former deputy secretary of the Department of Immigration Abul Rizvi welcomed Ms O’Neil’s comments, noting the old business migration program of the 1980s had been abolished in the early 90s for the same reasons. “The visa should never have been recreated,” he said. “The big problem will be what (to do) with the 30,000-plus backlog of applications.”

The Grattan Institute also applauded the development, urging the government to abolish the entire Business Investment and Innovation Program.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout