Toto Bergamo Rossi is Venice’s custodian of beauty

As a born and bred Venetian, and with a background in restoration, Toto Bergamo Rossi is ideally placed to be the guardian of the former republic’s exquisite legacy.

For many, Venice is a place of dreams, magic and romance. But it is also one of the most fragile cities in the world, blighted by over-tourism, merciless acqua alta, and the large cruise ships that for years have been devastating for the lagoon and the city itself.

Today, there are very few who know Venice as well as Francesco Bergamo Rossi. Born into a Venetian family, Francesco – called simply “Toto” by his countless friends and admirers around the globe – knows the city like the back of his own hands.

After all, given his long career as an expert stone conservator, those same hands have cleaned and restored the monuments of doges, and many other buildings and marble monuments all over the city.

“Here in Venice, sculpture was the favoured medium through which civic virtues could be allegorically represented, and the heroes and doges of the Republic celebrated,” he writes in Maichol Clemente’s book White Marble and the Black Death.

Toto Bergamo Rossi learned the craft of restoration on a UNESCO scholarship, and began as an apprentice restorer working on the scaffolds at the Basilica di San Marco, the very heart of Venice.

The projects that followed were likewise spectacular: the Doge’s Palace, Tiepolo’s frescoes in the Ca’ Rezzonico Palace, Veronese’s frescoes in the Church of San Sebastiano.

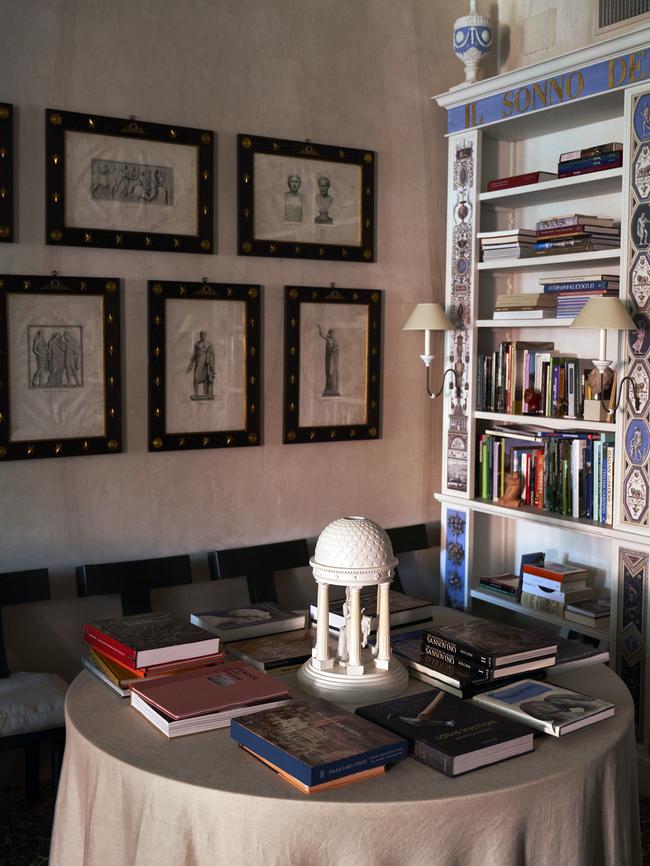

From 1995 to 2010, he owned an art restoration firm named after the Florentine architect Sansovino, who brought the Mannerist, or Late Renaissance, style to Venice at the end of the 1520s. The firm’s first project was the cleaning of the funerary monument of the Doge Giovanni Pesaro, inside the Basilica of Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari.

This began Toto’s love affair with the monuments of the doges of Venice (there were 120 over a period of a thousand years).

He closed his company in 2010 to serve as the director of Venetian Heritage, a nonprofit organisation dedicated to the safeguarding of Venice’s cultural patrimony through the preservation of the former republic’s legacy of art, architecture, literature and music, and through the promotion and exhibition of Venice’s rich contributions to the arts.

The borders of La Serenissima (“the most Serene Republic”, honoring the thousand years of peace that reigned in Venice) extended down the eastern edge of the Adriatic Sea and beyond, to Greece, Cyprus, and Turkey.

Venice owned all the cities along the coast except Dubrovnik (Ragusa), which remained an independent republic until 1808. Thus it is no surprise to learn that Toto spearheaded a Venetian Heritage campaign to restore Venetian Renaissance monuments in Trogir and Split, Croatia.

The seven years he dedicated to these projects brought him an immense personal reward when he discovered and fell in love with the small island of Lopud, which can be reached only by boat from Dubrovnik.

With an area of about 5sq km, no cars and a population of less than 300, it is surrounded by crystal-clear waters and was once a trading post for Greeks and Romans.

Franciscans settled there in 1483 and a large monastery was active until 1873, but the complex began to deteriorate over time. After securing a long-term lease from the church of Dubrovnik, Toto lovingly restored the small chapel and a part of the nuns’ room – they were in such a state of ruin that trees were growing inside the tiny monastic cells.

It is to this paradise, without the cars or mass tourism that plagues his home city, that Toto retires to do research and write his books.

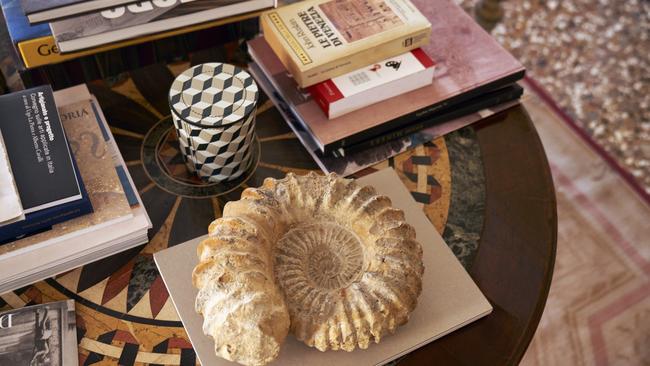

Among his publications are a sumptuous guide through a myriad of palazzi, Inside Venice: A Private View of the City’s Most Beautiful Interiors, and a book that covers a topic close to his heart, the first exploration of 120 dogal tombs over six centuries, Monumenti dei Dogi: sei secoli di scultura a Venezia.

It is Toto’s determination and undying love for Venice that inspires projects such as the exhibition he created in what used to be a sleepy, state-owned museum, the Palazzo Grimani, a place he charmingly calls “la bella addormentata” – the sleeping beauty – or the work he has done on the Ca’ d’Oro.

He talked about these projects and so much more as we sat together one hot summer afternoon in his beautiful Venetian office.

What is the difference between the Toto profiled in Vanity Fair 15 years ago and the Toto of today?

Well, the Toto of 2007 was a young man – almost 40 actually. At the time, I still had my restoration company, Sansovino, and I was concentrating on my own team and the works we were restoring in Venice, Dalmatia, Moscow, everywhere. I prefer the Toto of 2022, because I have learned that what I am doing now is more dedicated to what I can do for other people, not just myself. I hope with beauty we can inspire more young people to do the right thing.

I always say, we are not all lucky enough to have cultivated parents and people around us, so it should be the duty of schools to impart knowledge and raise the level of culture. But this doesn’t always happen. Thus, in our little foundation Venetian Heritage, we are trying to promote what exists already and give keys of access to people.

What does this mean exactly? When you make an exhibition, it should look sexy and accessible to the general public – not just for art historians who already know about it. We like to think we are spreading seeds in the garden; the winds and rain take some away, but some seeds stay. I am trying to spread the seeds of artistic appreciation with our foundation.

Do you see yourself as something of a style icon?

Toto: I think it is just part of the packaging. I was born and raised here in Venice, and was always captured and entranced by all the beautiful things around me: statues, sculptures, façades, museums, churches, etc., so perhaps this is why I’m thought to have good taste!

Is “taste” something you are born with? And who influenced you the most as a young man?

As a child, I was staying a lot with Elisabetta and her mother, Maria Teresa Rubin de Cervin Albrizzi, because my mother was not very present. Maria Teresa and her husband, a music composer, were separated, so they lived on different floors in their Palazzo Albrizzi.

The palazzo is still in their hands after 400 years. Maria Teresa was the daughter of a well-known Italian diplomat who travelled a lot, and she grew up with that cultured lifestyle. Thus, when she came to Venice, she did not want to just play the wife of a baron. She had greater ambitions and her curiosity was limitless. She had degrees in archaeology and art history, and she loved being around brilliant people.

So life in the palazzo was not a social salon, it was more an intellectual salon. She would call and say that there were 10 people coming over for dinner, and we kids had to improvise and prepare.

And then a Nobel prize winner, an important actor, a great art historian, would arrive. So she exposed me in an international way to interact with people. She was the director of UNESCO’s Venice office from 1973 to 1991, at the time a very important position that came into effect after the great flood of 1966.

This UNESCO office, in essence, launched the many private committees that now exist to help Venice survive.

I love that you are basically living her legacy in a way.

Absolutely. Unfortunately, Maria Teresa died in 2004, but I feel she is still with me. She was the mother I never had, but more than that: a professional guide and a guide on how to live a good life, someone who explained in very few words what is important and meaningful.

How about a father figure? Is there someone you looked up to? I always think of you and James Ivory, because he wrote such a beautiful foreword to your marvellous book Inside Venice – one of my prized possessions, by the way.

Yes, I greatly admired James Ivory. Maybe because of the unique way I grew up, I have always been intellectually attracted to older people who were doing important, beautiful things.

Normally, as a young person, you generally interact with people in your own age group until you are about 30 and only then begin to mix with older people. Instead, for me it was normal to have friends of all ages. For example, Hubert de Givenchy was the most amazing gentleman, with the most exquisite taste.

For a new visitor, how would you describe the perfect day in Venice? What shouldn’t they miss?

Although I’m not a religious person, I love going to a Venetian church. For me, it is like visiting a beautiful museum where the works of art were put there by the artist who knows the space exactly: the light from windows, the perspective... And there is nothing better than to see an original Bellini in its own frame, hanging on the same wall on which it has hung for 500 years.

So, I recommend that visitors go inside the churches – it does not matter whether you are religious or not.

The Venetian churches of their time were what the Venice Biennale is now in our time. Wealthy, cultivated people of the time could only express themselves then through monuments or paintings inside the churches, and this is why you have masterpieces in every church.

Visitors should go into little churches in Cannaregio – for instance, enter the Madonna dell’Orto and you will see square metres of splendid Tintoretto paintings, and some beautiful sculptures. Or go to the often-empty church of Sant’Alvise for amazing paintings by Tiepolo that most people never see.

Or visit the Basilica dei Santi Giovanni e Paolo, known in Venetian as San Zanipolo, in the Castello sestiere. It is the Pantheon of Venice, with tombs of 27 of the doges, and extraordinary artworks by Bellini, Veronese and more.

You can be in the church for hours, with only a handful of others. (A special tip about churches: if you encounter a half-closed door, just push it open and go in!)

Venice was a republic, so it was quite forbidden to celebrate private individuals. For this reason, there are no streets or squares with names other than those of saints.

It was also forbidden to celebrate people in a public place, which is why Venice has only one such monument: Verrocchio’s equestrian statue of the condottiere Bartolomeo Colleoni. [On his mother’s side, Toto Bergamo Rossi is a descendant of Colleoni, a leader of a troop of mercenaries in the Venetian. In his 1475 will, Colleoni left a gift to Venice of 100,000 ducats with the provision that a monument be built to him in front of the Basilica di San Marco. The Venetian state accepted the donation, but since personal monuments were not allowed in the main square the monument was erected in front of the School of San Marco. It is still there, by Venice’s oldest working hospital, San Giovanni e Paolo.]

Have you been to Australia? Do you have any connections there?

I have some dear friends there like Simon and Catriona Mordant. I would love to collaborate one day with a beautiful and important museum in Australia. We could share some of the lesser-known works of Venice that are nonetheless masterpieces, as we are doing with France.

Our organisation Venetian Heritage works with state museums in Venice that belong to the Ministry of Culture, such as the Museo di Palazzo Grimani. Now we are working on updating and restoring the Ca’ d’Oro.

In order to be able to do this, we will send part of the permanent collection to a new museum in Paris for a four-month exhibition from November 2022 to February 2023, at the recently opened Hôtel de la Marine: “From the Grand Canal to Place de la Concord: Treasures of the Ca’ d’Oro.”

You mentioned making exhibitions sexy and appealing to people, and you have done that with Palazzo Grimani, which used to be such a depressing place to visit. How did you think of this and how difficult was the process?

I think at night about what to do next, and thank God I still have good ideas! Even though we are only four people, we are a great team, and we really believe in what we are doing.

The Palazzo Grimani was la bella addormentata, a beauty just there sleeping. It reopened in 2009 after 20 years of restoration, but the public had to figure out what it was, with no explanation.

How many people know Giovanni da Udine: was he an assistant to Raphael, or of the school of Giulio Romano? Which is it? You must explain to people – why Grimani, why this, why that – and put objects inside for context.

You cannot just restore a building and open it without other efforts. So we have been able to fill the spaces with wonderful exhibitions that animate the spaces.

And how about Ca’ d’Oro? How did the restoration of that start?

The Ca’ d’Oro, again, was a bella addormentata, because everyone knows the façade, and the place is so beautiful, but people rarely enter.

If foreigners want to know when Venice was great, the Golden Age of the 14th and 15th centuries, the Ca’ d’Oro is exactly that. The house with the courtyard with the outdoor stairs with all these beautiful loges, Gothic windows.

When people think of a Venetian palace, this is it, with beautiful gothic windows. The majority of the city was built at that time. If you look at a map of Venice, the city plan is not a Renaissance city, it is a Gothic city.

Visit the Ca’ d’Oro next time you are in Venice! Everyone knows the name, “the golden house”, but people rarely go inside. It is the best gothic façade on the Grand Canal but the number of visitors inside is very low.

You were named Venice’s Honorary Consul of Sweden. Tell me about that.

I accepted the position because Sweden is a beautiful country and there is a strong link with Venice. There was a famous Grand Tour of Swedish King Gustav III to Italy, during which he spent more than a week in Venice.

The Gustavian era is such an elegant period at the end of the 18th century – a mix between the French Louis XVI style and the Italian Neoclassicism. I am very interested in creating an exhibition based on this era.

What do you think is the future of Venice?

In many ways, Venice today is more of an open-air museum than a city. Venetians are leaving, driven out by the conversion of apartments into short-term rentals. Elementary schools are closing and becoming hotels.

I want my city to be a museum, but in a positive way – preserved, with people who live inside. In fact, Venice is the most international city in Italy, and more and more is becoming a capital of the arts.

But globalisation is a big problem for Venice, and there need to be rules for travellers. In many ways the city is still being run as it was 50 years ago, when I was born. But we have to face the fact that we must be organised.

Yes, Venice is an open-air museum, but that’s not a negative. We go to museums to preserve and transmit art and culture. We should use the Louvre’s reservation system to run the city, especially for the big groups.

They have to make a reservation to come to Venice, especially for short periods. The money would be used for the maintenance of the city and canals. If you do not have a reservation, you cannot come in!

Very often you are in the company of celebrities when they come to Venice and you inspire them to endorse the mission of the Venetian Heritage.

The idea for them that someone is still living in Venice, and is an insider who can open doors to some incredible places, is special.

For me, it is a privilege to show them Venice through my eyes. I am a generous person; I love to give whatever I have, and I love to share whatever is around me. I think that is why I have been given this role in the Venetian Heritage.

I am very transparent in what I do. And whatever I do, I do for one reason. And it is always the same: Venice.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout