The surrealist movement is making a comeback once again

From Kate Winslet’s new Lee Miller biopic to blockbuster exhibitions, why this avant-garde spirit is back, relevant and even hip.

There is a delightful scene in Lee, the film directed by Ellen Kuras and based on the life of war correspondent and artist Lee Miller, in which Miller, played by Kate Winslet, sits scantily clad at a picnic with similarly déshabillé female guests – and fully clothed men, it must be noted – in a French garden by the sea. The group, composed of fellow Surrealist artists and poets, lounge languorously as they debate the impending war. The hedonistic scene introduces us to Miller’s husband, artist Roland Penrose (Alexander Skarsgård), with whom Miller lived a passionate and creative life.

It is a pivotal moment in the film, connecting the two parts of Miller’s extraordinary life: her before, as a model, artist and muse to artists such as Man Ray; and her after, as historically significant war correspondent, a celebrated artist and visionary in her own right. Miller was one of the first photographers to witness the emancipation of concentration camps, capturing some of the most indelible images of World War II.

Her approach to war photography was deeply informed by her Surrealist spirit, you could say. She brought to her images a unique eye, the ability to find beauty and meaning in the grotesque. She said of her work: “There were lots of things, touching, poignant or queer, I wanted to photograph.” The war, it seems, gave her exactly that.

Lee shows the artist taking shelter amid fierce shelling, stopping to take a photograph of a discarded German soldier’s boot, out of which spills ammunition that, at a glance, resembles a skeleton. This highlights Miller’s interest in the objet trouve, a found object that takes on an aesthetic quality in a new juxtaposition.

The approach can be seen in her Vogue fashion work, but also in her war-correspondence photography; a piano appears remarkably intact amidst a pile of rubble while elsewhere, a group of emancipated prisoners stare blankly at a pile of human bones. The incomprehensible, made visible. Lee – its screenplay co-written by former Vogue Australia editor Marion Hume – captures how Miller documented the horrors of war, not as a detached observer but someone deeply affected by the frequently surreal nature of human suffering and resilience.

Miller’s work would have gone largely unseen and uncelebrated were it not for the efforts of her son Antony Penrose, a photographer himself, who discovered her archive after she died and sought to secure his mother’s legacy. Penrose was heavily involved with Lee, helping to flesh out his mother’s contribution to art, culture and history more generally. “My mother’s style was so instinctive, so automatic that she could not describe it,” Penrose says. “It was a systemic part of her way of seeing with an eye formed when she entered the world of Surrealism. Although she was capable of taking faultless fashion shots, that Surrealist eye sought its expression when confronted with scenes totally beyond the normal world. Her war was full of surreal moments she harvested in a choice that was entirely natural.”

Wish Magazine’s design issue is out Friday October 4. Inside your copy of The Australian.

Kuras’s thoughtful film comes at a crucial point in art and social history, because 2024 marks the 100th anniversary of poet André Breton’s Manifestoes of Surrealism. Breton’s text, which was inspired by writers such as Lewis Carroll and the psychoanalytic theories of Sigmund Freud, would become a lightning rod for a group of artists, poets and writers, including Miller and her milieu, laying the foundation for Surrealism, which became one of the most influential avant-garde art movements of the 20th century. Its influence was felt worldwide, including in Australia, as seen in the work of artists such as Sidney Nolan and James Gleeson.

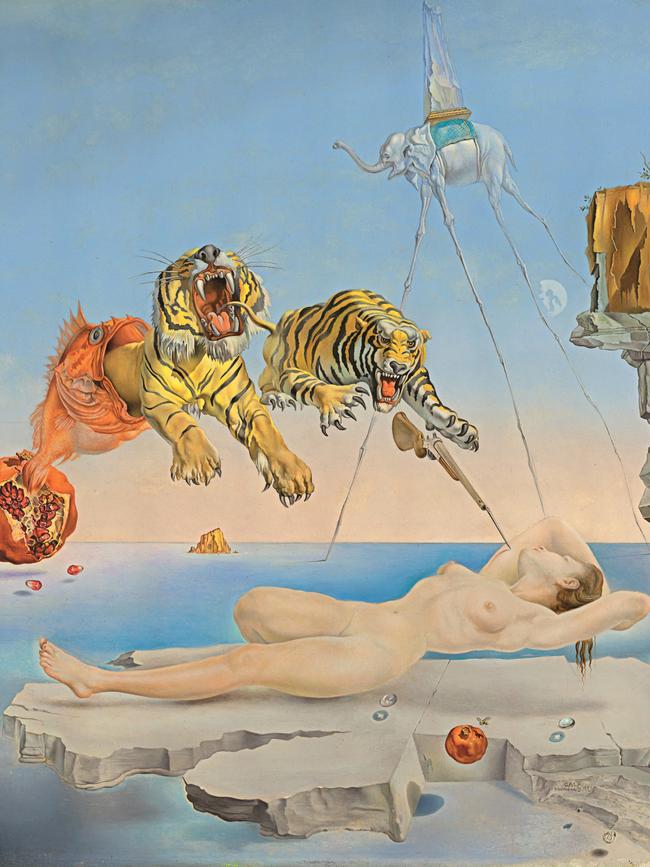

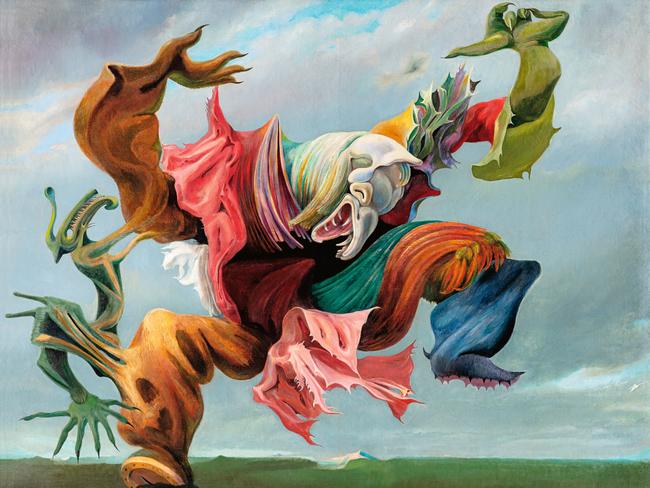

Breton’s manifesto defined Surrealism as “pure psychic automatism”, a way of expressing the unconscious mind without the constraints of rational thought, morality, or aesthetic standards; it challenged the dominance of rationalism in Western culture, which Breton believed led to the horrors of World War I. He advocated for a new artistic and literary movement that embraced the irrational, the dreamlike, and the unconscious, ideas widely adopted by artists and writers including Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, René Magritte, Man Ray and many others, promoting Surrealist techniques such as automatism, collage and the use of chance in the creative process – all aimed at accessing the unconscious mind. Breton declared, “The mind of the man who dreams is fully satisfied by what happens to him. The agonising question of possibility is no longer pertinent. Kill, fly faster, love to your heart’s content.”

The current state of the world is not dissimilar to what Miller experienced; combative and cultural wars are being waged on multiple fronts. Political uncertainty reigns, absurd fake news abounds and the global economy is in a cost-of-living crisis. Antony Penrose concurs: “We have returned to a world the Surrealists would have recognised, where governments are controlled by commerce and people are reduced to an exploitable commodity. The cycle is returning to rebellion, and once again, we may find art could lead us to a fairer, better world. Maybe even the ‘Brave New World’ Lee hoped World War II would deliver.”

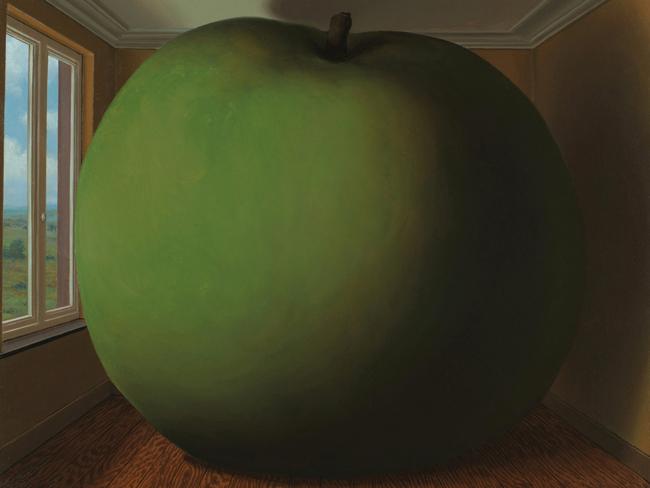

It is fitting that Surrealism is having a moment in this centenary year. Numerous exhibitions are planned, the most significant of which is Surrealism: The Centenary Exhibition at Paris’s Centre Pompidou, which explores the movement’s influence on art, literature, and culture, and features Breton’s original manuscript alongside landmark works such as Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory (1931), famous for its melting clocks, and Magritte’s best-known work, The Lovers (1928), alongside the work of lesser-known Surrealist artists.

Closer to home is an exhibition of the work of Magritte, the Belgian Surrealist, at the Art Gallery of New South Wales from October 26 until February 9, 2025, curated by Nicholas Chambers. Magritte features exceptional loans from major international galleries and is a genuine coup for Australia. More than 100 works, many never before seen here, chart the artist’s first avant-garde experiences in the 1920s through to his groundbreaking contributions to Surrealism.

“Even if they’re not familiar with Magritte’s work, viewers may well have a sense of déjà vu when they recognise echoes of his paintings in advertising, or cinema, for example, or begin to sense the ways his images have infiltrated visual culture at large,” says Chambers. “Perhaps more than any other European Surrealist, Magritte’s art broke free of the specific historical and artistic context in which it evolved.”

Surrealism’s influence continues today across culture, from visual art to cinema; from films such as Yorgos Lanthimos’s Oscar-winning Poor Things or Guillermo del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth, to advertising and design.

In July, the National Gallery of Victoria announced the acquisition of Dalí’s Mae West Lips Sofa (1937–1938), the last of five to enter a public collection, its design based on Dalí’s Mae West’s Face Which May Be Used As A Surrealist Apartment (1935), in which West’s signature blonde hair hangs as drapes, her eyes taking the form of two framed pictures, her nose a fireplace and her lips a two-tone sofa.

Surrealism finds its most comfortable fit in the fashion world. In 2024 the most boundary-pushing couture label is Schiaparelli. The house was founded by Elsa Schiaparelli in the 1920s and revived in 2012 (after its 1954 shuttering) by Italian entrepreneur Diego Della Valle, chairman and chief executive of Tod’s Group.

The reborn house honours the legacy of Schiaparelli – or Schiap, as she was known to her friends – who collaborated with artists such as Jean Cocteau and most famously with Dalí on the “lobster dress” worn by Wallis Simpson, the Duchess of Windsor. Schiaparelli’s nonsensical, whimsical designs – a hat in the form of a shoe, or a jacket mimicking a rib cage – challenged conventional notions of beauty and fashion.

Schiaparelli’s current creative director Daniel Roseberry, appointed in 2019, has revitalised the brand’s historical ties to Surrealism and pays homage to the movement via exaggerated silhouettes, fantastical trompe l’oeil embellishments, and unexpected materials – gold bustiers shaped like human torsos – that evoke the absurd and the mythical in an haute couture vision that seemingly resonates with the absurdity of the Zeitgeist.

The Australian-born enfant terrible Leigh Bowery, a performance artist and eventual fashion icon who embodied Surrealism through his avant-garde costumes and provocative performances, will be the subject of a major survey at the Tate Modern, London in January next year. Like Surrealism, Bowery’s outlandish, often grotesque designs and personas challenged traditional aesthetics, blurring boundaries between reality and fantasy. The Melbourne-born Bowery’s enduring influence can be seen in the work of Lady Gaga, musician and writer Nick Cave, and Balenciaga under creative director Demna.

In short, Surrealism is back, relevant, hip even. The contemporary art world is particularly in thrall. Ariana Papademetropoulos, who shows with US gallerist Vito Schnabel, is another artist to watch. A new book by Robert Zeller, New Surrealism: The Uncanny in Contemporary Painting, points to the latest crop of artists looking back to go forward, and features contemporary artists including Anna Weyant and Ewa Juszkiewicz.

The secondary art market has also reassessed Surrealism, which means that under-recognised artists associated with the movement, noticeably female, including Remedios Varo, Dorothea Tanning and Dora Maar, are being reconsidered – Lee Miller included. In May this year, the sale of the late Surrealist artist Leonora Carrington’s painting Les Distractions de Dagobert for more than $US28.5 million ($42 million) at Sotheby’s surpassed the price of renowned Surrealists such as Ernst and Dalí, and shattered Carrington’s previous auction record of $US3.3 million. The sale placed her among the top five most valuable female artists alongside the likes of Frida Kahlo and Georgia O’Keeffe.

In the words of Breton, “Let us not mince words: the marvellous is always beautiful, anything marvellous is beautiful; in fact, only the marvellous is beautiful.” It sounds like an invitation to dream.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout