Saving Swifts: inside one of Australia’s most ambitious renovations

Swifts in Sydney’s Darling Point, a monument to the city’s boom times, was nearly lost to history. But its present owners are restoring it to its former glory.

Today it’s the mining magnates and tech titans who are among the richest people in the country, but a century and a half ago it was the brewery barons who made headlines because of their extraordinary wealth. Although when it came to their lifestyle their tastes were more in keeping with champagne budgets than anything as unpretentious as beer.

The 1880s was a boom period in Australia as money from English banks flooded in to fuel the expansion of the colony. The brewery industry also experienced phenomenal growth at the time. The number of breweries in New South Wales reached an all-time high in 1880.

In 1872, brewer Robert Lucas-Tooth, took ownership of a significant parcel of land in Darling Point in Sydney, now one of the city’s most exclusive suburbs, and set about building a sandstone mansion in the Gothic Revival style that included a tower, castellated walls, a ballroom, servants’ quarters, extensive gardens and a carriage house, among other extravagances. He named it Swifts and based its design on his ancestral home, Great Swifts Manor in Cranbrook, Kent.

Lucas-Tooth had been born in Sydney but was educated at Eton in the UK. On his return to Australia, he joined the family brewing business and oversaw the construction and expansion of Swifts, which was also based on the design of Government House in Sydney, by the French architect Gustavus Alphonse Morrell. Lucas-Tooth married his first cousin, Helen Tooth, and had six children, before returning to England in 1900, where he ran for parliament. When he left Sydney he sold Swifts to one of his business rivals, the German emigrant brewer Edmund Resch, who originally came to Australia to make his fortune in the goldfields but found it in beer instead.

Doug and Greta Moran, founders of the Moran Health Care Group, and their six children purchased the house in a mortgagee-in-possession sale in 1997 for a reported $12 million after it failed to sell when offered by tender the year before and again later at a public auction. In 2013, their fourth child, Shane Moran, acquired full ownership of Swifts from his siblings. At the time of the 1997 sale, the building was not yet on the State Heritage Register and there were serious concerns it would be demolished and the land redeveloped. No one wanted to take on what would clearly be the herculean task of restoring the enormous building, which had fallen into a state of serious disrepair. The acquisition by Shane Moran, however, ultimately saved Swifts from possible destruction and over the past two decades he has been painstakingly restoring, modernising and rebuilding it – not as a living museum, but as a family home for him, his wife Penelope and their four children.

Swifts is one of the city’s few surviving grand Victorian mansions that is still in use as a private home. Its restoration is an ongoing project and it would be inaccurate to say that the photographs on these pages, shot exclusively for WISH Magazine, are the definitive images of the completed house. Owning Swifts, says Moran, is akin to painting the Sydney Harbour Bridge: no sooner do you cross one task off your to-do list than several more have been added.

“We started this [renovation] process not knowing how big it was going to be,” says Moran. “It was far bigger than we ever anticipated. I have lists of what’s got to be done and by when, and how it’s going to be funded. And sometimes I get frustrated because something else crops up that needs fixing. Once I came to the mindset that it’s never ending, it actually became far more enjoyable. You know that every day there is going to be something new, not a problem necessarily but a discovery of some sort. So there’s a lot of fun in it.”

-

“We would steam off layers of paint and wallpaper and sometimes I would hear workers scream because they’d discovered something extraordinary, like painted phoenixes [on the vestibule ceiling]”

-

Moran estimates that it costs in the vicinity of $1 million a year to stay on top of the maintenance and restoration of the estate (including land tax, energy costs and other expenses). To allay some of those costs, he lodged a development application with Woollahra Council last year seeking approval to hold up to 52 events at the house each year. The application received more than 100 objections and was referred to the council’s Local Planning Panel, which refused the application in December. Moran is planning on resubmitting the development application later this year, with some modifications.

The history of Swifts, the construction of which was completed in 1877, reads like a script from the television series Downton Abbey. There have been several battles over its ownership. During the Great War it was thought the house’s owners, the Reschs, who were German nationals, couldn’t be trusted with such a commanding view of Sydney Harbour as their location could easily be used for purposes detrimental to Australia’s security. It didn’t help that they reportedly flew a German flag atop the building at one point. There was a sex scandal of sorts in 1925 involving the owner and a bride left at the altar that resulted in a court case that rocked Sydney society and the trial was turned into a popular silent movie. The house was involved in the war effort during World War II as a hospital and a rest centre for wounded soldiers. At one point the Catholic Church owned it, and it was home to cardinals and hosted two popes on their respective visits.

Edmund Resch had two sons – Edmund Jr and Arnold – who couldn’t agree on the direction of the family company or their father’s estate when he died and were ordered by the Supreme Court to sell the house to settle their dispute. It was bought at public auction by Edmund Jr. Arnold Resch left Australia to live in the Channel Islands and is believed to have died in 1942 in a German prison camp. When Edmund Resch Jr died in 1963 he had no children and left what is thought to be the largest estate ever lodged for probate in Australia. Despite being a Lutheran, he left two-thirds of his estate, including Swifts, to the Sisters of Charity and the Catholic Church. It was left to the nuns on the condition that it be used to establish St Vincent’s Private Hospital in Darlinghurst and that the house could not be sold for a period of 20 years.

In 1986 it was bought by the horse trainer and investor Carl Spies for $9 million – a record for a non-waterfront house at the time. A few years later, however, Spies found himself overextended, thanks to the recession, and he was pursued through the courts for his failure to make mortgage payments (to his bank and the Catholic Church). More than 450 pieces of furniture were sold at auction in 1992 before the house was finally placed on the market by St George Bank in late 1996. That meant very little of the original fabric of the interiors remained when the Morans acquired it. “There were a couple of chairs that we found in the old stables and a couple of items from the Resch era in the dining room, but very little else,” says Moran. “That has been part of the challenge – filling up the empty spaces.”

When the family took possession of the property, which sits on 11,000sq m of land, it was in urgent need of repair. A lot of the stonework on the façade had been battered by the north-easterly winds and the salt air from the harbour over the past 100 years and needed to be replaced. A stone colonnade outside the ballroom was sinking into the ground and at risk of collapse, so substantial engineering works were needed to prevent that happening. Some of the ceilings throughout the house had fallen in and birds were flying around the rooms. And the expansive slate roof also needed to be restored. Making the building safe and secure, therefore, was the first priority. Once that was done, attention turned to decorating the house, which has more than 60 rooms.

-

‘Despite its vast size, Moran says the house is extremely habitable. All four of his children still live there and there is always a guest of some sort to accommodate. “The house couldn’t be more lived in, even if we do have to ring a bell to get everyone to dinner,”’

-

“It was really a question of which approach to take,” says Moran. “Do we take the rooms back to something simple or do we go the full hog and go back to the Lucas-Tooth era?” Moran chose the latter and engaged heritage architect Clive Lucas to oversee the restoration. A new kitchen and conservatory were built at the back of the house, and some smaller rooms, mostly servants’ quarters, were opened up and windows enlarged. “We genuinely wanted to make it, while liveable, as close as possible to how it originally was, which was actually very functional.”

Sometime after the restoration work started, a marble fireplace was discovered buried at the bottom of the property. Clive Lucas decided that because it was made from black marble it would have been the missing one from the dining room, as the space was often used to lay out the bodies of people after they died. Later, the original dining table turned up with an antique dealer and was acquired by Moran. The Moorish-inspired smoking room was also hidden behind false walls and was remarkably intact when it was discovered. “We would steam off layers of paint and wallpaper and sometimes I would hear workers scream because they’d discovered something extraordinary, like painted phoenixes [on the vestibule ceiling],” says Moran.

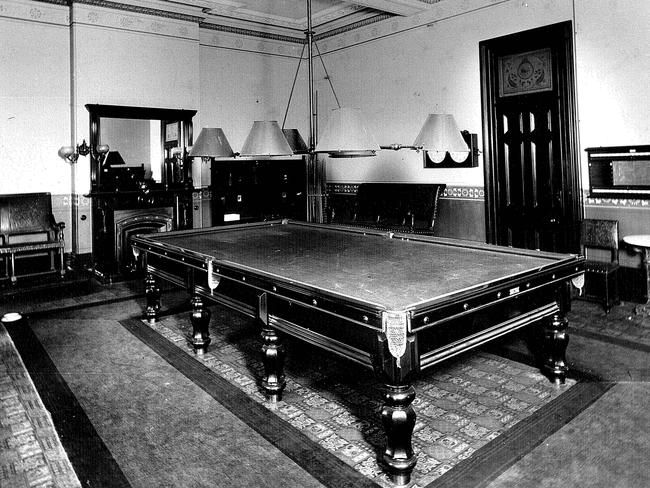

A new pool was built on the grounds as part of the modernisation of the estate, as well as an extensive garage underneath the tennis court that houses a collection of rare and vintage Rolls-Royces owned by Moran’s older brother. A historic and restored Australian-made organ by Fincham & Hobday replaced a German-made one in the ballroom, which is lined with paintings of famous composers, providing an insight into the musical tastes of the upper classes of late 19th-century Australia.

Despite its vast size, Moran says the house is extremely habitable. All four of his children still live there and there is always a guest of some sort to accommodate. “The house couldn’t be more lived in, even if we do have to ring a bell to get everyone to dinner,” says Moran.

As for his favourite part of the house – it’s the library. “It’s wonderful being here. I love this space, it gets the morning sun and I love being surrounded by books. It’s a really nice place to work and to focus.

“My wife sometimes jokingly calls the house the big black hole, but she knows the passion I have for history and this house. We’re very fortunate to have a business that can support the work we do on it.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout