How fat are your sneakers?

The sustainable sneaker brand is on a mission to get people to pay as much attention to their carbon emissions as they do to their calorie intake.

Tim Brown and Joey Zwillinger convinced the world to buy environmentally sustainable sneakers made out of wool and trees. An extraordinary proposition, yet five years later Allbirds is worth $US1.7 billion and its sneakers are sold in 35 countries. Now its founders have much bigger plans. They want to change the world one label at a time by making consumers care as much about carbon emissions as they do about calories.

“When we started the business in 2016, we were trying to do the right thing. Fast forward to now, and I think one of the greatest achievements is literally to be the first company to start labelling products with the kilos of carbon produced when we make something,” Brown says. “We are starting to put it out there – however imperfectly – to try to introduce measurements, drive change and drive consumer decision-making. This is chapter two of our conversation.”

The Allbirds team has devised an environmental equivalent of a nutrition label for their products that gives their customers a measure for the amount of carbon created by their footwear. This one singular number takes into account the emissions produced by the material and manufacturing of the shoes, as well customer use (for example, in machine washing) and what happens after the sneakers are discarded.

“The environment is on people’s minds but truly connecting them to carbon is an ongoing challenge,” says Jad Finck, Allbirds’ vice-president of innovation and sustainability. “We wanted to make a single number like calories in food. Calculating calories is complicated, but everyone knows to focus on that fact that fewer calories are better and so people started to get the hang of it.”

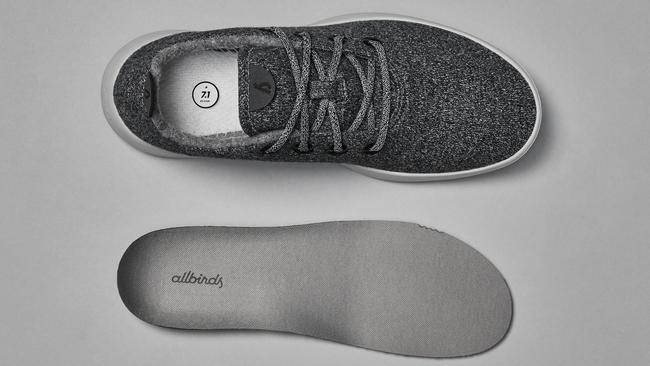

The San Francisco-based start-up is the first fashion brand in the world to label its products with their carbon footprint. Allbirds shoes emit an average of 7.6kg of CO2e (carbon dioxide equivalent emissions) for each pair – the ones made of wool are 7.1kg, trees are 8.1kg. This is the equivalent of driving 30km in a car, putting five loads of washing in the clothes dryer and making 22 chocolate bars. In comparison to other clothing products in the market, an average pair of shoes has a carbon footprint of 12.5kg, while a pair of jeans comes in at 29.6 kg and a T-shirt emits 13.6 kg.

This is not the only innovation keeping them busy at Allbirds. The company has branched into apparel, releasing underwear, socks and even T-shirts made of discarded crab shells (yes, you read that correctly). It launched a new running shoe called the Tree Dasher and entered into partnership with one of its biggest rivals – Adidas – to create a high-performance sneaker with the lowest carbon footprint possible. “Hey Allbirds, you up? We’ve been thinking… do you want to tackle climate change together?” reads the Adidas tweet announcing the collaboration.

Allbirds is also venturing into the world of plant-based leather by investing in a company called Natural Fibre Welding that makes leather alternatives from vegetable oil and natural rubber. It hopes to release its first plant-based leather shoes by the end of the year.

“This product has the potential to be a 98 per cent reduction in the carbon intensity when you compare it to bovine leather,” says Zwillinger. “This is the key metric. If we can get the carbon number down to zero, this is how we are going to be able to fight climate change. This is a great way to show this massive industry how it is possible.”

This is the second time WISH has spoken to the founders of Allbirds. We first interviewed Zwillinger and Brown in October 2018 in their office in downtown San Francisco. The company was not even three years old but it was already generating significant buzz, sales and investment, and counted Oprah Winfrey and Barack Obama as fans. Brown and Zwillinger had met a few years earlier – through their wives –when Brown, an ex-soccer player from New Zealand, was attempting to create a sneaker made of his country’s famed Merino wool and Zwillinger, a biotech engineer and a renewables expert, was hunting for a start-up with a sustainability focus. It was a perfect match.

“Tim flew out of London, where he was living, and we had a three-day session [at my house in San Francisco] where we just talked about the potential of the business from a financial perspective, but also whether we thought it would make a big enough impact [for us] to be proud to work here,” Zwillinger told WISH in 2018. “We came to the conclusion pretty quickly that it would be.”

Brown and Zwillinger focused on the comfort and design of their shoes – they were going for a very different clean and minimalist look with no visible logos – and initially promoted this instead of sustainability. When they launched their first shoe, the Wool Runner, in 2016, the emphasis was on how the sneaker performed over the fact that the upper was made of wool, the insole from castor bean oil and the shoelaces from recycled plastic bottles. It worked. TIME declared Allbirds the most comfortable shoes in the world and soon they were adorning the feet of actors, politicians and tech titans.

“An insight I find really interesting is that people don’t yet buy for sustainability, they buy for great products,” Brown said back in 2018. “When you hear something is sustainable, you automatically assume negative connotations; either they are going to be more expensive or not as good. So the idea with Allbirds is we haven’t marketed sustainability, we have just sold great products and the customers have worked out that we make it as sustainable as possible.”

Chatting with Brown again two and half years later, and unfortunately over Zoom instead of in San Francisco, thanks to COVID-19, WISH asks the New Zealander whether he still believes this. Has the consumer changed?

“I think it is true today as it was then,” he says with some passion, “and that is because the answer to solving the problem of climate change is not with more environmentally sustainable products but by making great products sustainable.”

Brown has also definitely noticed a heightened anxiety around global warming – especially among young people – and they want to see action on climate change immediately instead of “esoteric pledges” for 2030 or 2050. “We are also seeing it in our own team; they are demanding that we go

harder, go faster, be clearer,” he says. “And all this stuff needs to happen now.”

Zwillinger believes consumers have become more aware of the environmental impact of things they buy, especially since the global climate change marches in September 2019 and the pandemic. “People still don’t want to sacrifice great products for sustainability, but they are starting to look for more sustainable items,” he says. “Even if you just look at search term trends on Google, the term sustainable fashion has gone up 600 per cent. Things have changed, which is super positive, but I think you also have to be careful, because if you walk down the street and ask 10 different people what sustainability means you will get 10 different answers, so sustainable fashion can mean anything.”

He believes brands are defining what being environmentally sustainable is to the consumer and this has a downside; they can serve their own interest first and the future of the planet second. That is why Allbirds went down the path of creating that single carbon figure. Not only does it mean they are being transparent with the consumer, it also means they are being transparent with themselves.

“The environment is under duress right now so we wanted to choose something that could hold us accountable to this idea of what it means to be truly sustainable,” Zwillinger says. “And we want this carbon label to be a beacon. Other companies have started to adopt it, which is fantastic. Unilever has started to use it, Logitech has started to use it. We have not seen anyone in our industry adopt it but we think it will come, it will become standard, and we are really excited by that. “Maybe at some point in the future we won’t be the company with the lowest carbon footprint, and that in turn will put the challenge back on us to keep driving it down from zero and beyond. This is like we are in a race and everyone needs to get on and get down to zero or even better.”

This sharing of ideas within the $US365 billion global footwear industry – as uncompetitive as it may sound – is not new to Allbirds. When it made sneaker foam out of cane sugar (known as SweetFoam) in 2018, it made the process available to anyone interested as a way to encourage them to go down the same path. It has referred more than 100 companies to the partner in Brazil that produces it and other brands are launching footwear using the technique.

“If we are going to be leaders in sustainability and we are going to be the only ones that launched what we are doing 10 years later, then how much difference have we really made?” Finck says. “We need to make sure either the technology gets deployed or it at least inspires. It is important not just for altruism, but it is important for this stuff to get to scale for the prices to become commercial so it can be truly, widely deployed. We of course keep our special sauce, so to speak, our way of making that sneaker foam, but we want to get more people to do this.”

The latest innovation to come from Allbirds is T-shirt material made of discarded snow crab shells from Canada. So where does the idea to make clothing out of crabs come from? A desperate pitch at a Friday afternoon meeting?

Finck laughs and says it came from wanting to extend the comfort of their products – which is what Allbirds is known for. He began looking an anti-odour technology that would allow a T-shirt to stay fresh for longer and also reduce the amount of washing required. His team came across a powder made of crab shells, called chitosan, used by the medical industry as a bacteria inhibitor in bandages. The problem was it was designed for a single use and would not last on a T-shirt that was washed.

Allbirds solved this issue by finding a way to make chitosan into a fibre that could then be woven into a T-shirt. “It is basically dissolving crab shell powder down to what almost looks like honey. It then gets extruded – like pasta – through a very tiny spinneret and that makes very fine fibres,” he explains. “This is then dried and turned into yarn.”

The discarded crab shells are a byproduct of the seafood industry and Finck had some very funny conversations with the Marine Stewardship Council – a sustainable fishing body – as he wanted to make sure the crab shells they were using met top environmental standards. Allbirds was the first non-seafood company seeking accreditation from the organisation and the request was met with some disbelief at first. “The same way you have been asking all these questions, we were going through the process with the council over the phone, and they kept bringing people in on the call saying ‘you have to come listen to this, they want to make a T-shirt!’” Finck says, laughing.

As well as innovating a raft of new materials since they launched in 2016, Allbirds has also hit the accelerator on its retail footprint. It started with one store in San Francisco and now there are 22 across the world. The pandemic has slowed the expansion but crucially not stopped it, as both founders believe bricks and mortar stores are a powerful way to explain their ideas to the consumer. They plan to open new retail locations in Seoul, Japan and China by mid-year.

This month Brown and Zwillinger will celebrate the fifth birthday of Allbirds, and they have achieved so much more than they expected. “We have come a long way but I think with the environment there is a lot of unfinished business,” says Brown. “What comes with success is a really great opportunity and obligation to do more and advocate more,” adds Zwillinger. “We not only want to be a better company, we want to help contribute to a better way of living.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout