Grand tour of Tuscany

A leisurely road trip is the only way to take in the sublime pleasures of Tuscany, and you might as well do it in high style.

Every now and then a travel magazine will declare a rarely touted part of Italy “the new Tuscany”. If you don’t believe me, do an internet search for “the new Tuscany” and see how frequently it appears. This year it seems the new Tuscany is the Le Marche region on the east coast of the country, between the Apennine Mountains and the Adriatic Sea. Or is it Piedmont? A couple of years ago it was Puglia, in the heel of the boot. The new Tuscany is usually acclaimed as cheaper, less crowded with tourists and just as beautiful as old Tuscany.

With this near constant search for a new Tuscany, you’d be forgiven for thinking there was something wrong with the old one. But despite claims to the contrary, Tuscany has not been blighted by the hordes — you just have to know how to see it.

Yes it’s expensive, but what part of Italy isn’t? And yes it’s crowded with holidaymakers in the summer months. But once you get away from the bustling tourist meccas of Florence, Pisa and Siena, it’s possible to find a quiet corner of this region and discover for yourself the enduring appeal of its natural beauty, its cuisine and its history. And one of the best ways to discover Tuscany is by driving.

High-speed train travel in Italy is an excellent way to get from one city to another, but you’ll miss some of the country’s less celebrated, but no less charming, towns and villages if you don’t get behind the wheel of a car… and of course, hold on tight.

I am driving a Maserati Quattroporte S from Milan in Lombardy, through Tuscany and eventually on to Rome in Lazio. I’m in no rush so I’ve decided to do it over a week. I figure by then I will be so accustomed to Italian driving I’ll be able to handle the dreaded Roman traffic with ease.

But if I were in a hurry, I could be in Rome in time for a late lunch if I set off from Milan after breakfast. If you did that, though, it wouldn’t feel like hurrying — you’d just be keeping pace with Italian motorway traffic, which rarely moves at or below the legal speed limit.

The drive from Milan to Rome is just over 600km, and should take approximately 6.5 hours if you go via Bologna and Florence — a little faster if you take the E45 via San Marino. The speed limit on many of the highways in this part of Italy is a staggering 130km/h, and just keeping this Maserati at that speed (which, to be honest, in a Maserati just feels like a relaxed Sunday drive) means you’re being overtaken by someone in a clapped-out early model Toyota Corolla who seems intent on breaking the sound barrier, and on occasion also being given the finger, sometimes by the passenger as well as the driver, as the car passes you. It’s unnerving at first, but like a lot of things in Italy, you get used to it.

The last thing you should do is travel swiftly through Tuscany. It’s the kind of drive you want to last for hours, as you delight in the rolling hills, the never-ending valleys, the bales of hay scattered over the fields like a landscape painting, poppies strewn throughout the countryside, and of course the myriad Instagram-perfect Italian towns along the way. In Italy, however, the engineering of a Maserati and its trident badge – not to mention its unmistakable sound – is a matter of national pride. If you’re not driving in the manner in which this car with its 430 horsepower and V6 engine was designed to be driven, then to Italian motorway drivers at least, you don’t appear to know what you are doing. Hence the finger salute.

Heritage, tradition and culture are important to Italians. In 1929 in Cremona in the north of Italy, a Maserati V4 achieved a record-breaking 246km/h for a 10km stretch, a record that stood for nearly a decade. Maserati won the Targa Florio, an open road endurance race in Sicily that ceased in 1977, for four consecutive years from 1937. Maserati has won Grand Prix titles in Naples, Rome and San Remo, as well as the German Grand Prix and the Indianapolis 500. And Maseratis of various vintages have participated in the famous Mille Miglia, an open-road endurance race from Brescia to Rome that ran 24 times between 1927 and 1957. Driving a car like this is a privilege and not acknowledging its legacy with speediness is a slap in the face to the Italian drivers sharing the road with you.

The marque’s heritage in motorsports is very much part of the brand’s DNA today, even if its road cars such as this Quattroporte feel more like a classic luxury saloon than a speed racer. But this is still a Maserati, a car that has what many consider to be the most beautiful engine sound ever produced. A study by the British insurance company Hiscox a decade ago concluded that the Maserati sound might even have aphrodisiac qualities. Why an insurance company decided to study that is anyone’s guess. The point is, producing the guttural, gravelly growl of a Maserati when you overtake a slow-moving vehicle, or when you put the car into Sport mode, is one of the great thrills of driving a car like this. A Maserati really comes into its own when the car is driven hard, and on these roads you occasionally get the opportunity to do that.

At one of the hotels I stop at along the way, the proprietor tells me that Italy is a great place to break the law. He’s responding to my astonishment at how fast everyone drives despite the roadside warnings of speed cameras. What he means is that Italy is a great place for not getting caught. Italians drive however they want to on highways and it gets worse the further south you go. In the northern regions such as this one the roads are actually quite well maintained, even if the lanes are narrow and there are as many trucks on the road as there are cars. Whatever car you drive on these roads, you need to handle it with confidence. Despite their love of speed, Italians are actually pretty good at sticking to the right-hand lane unless they’re overtaking. While that might sound like courteous driving, they expect the right lane — the “slow” lane — to move at the legal speed limit at the very least.

Driving allows you to experience the real Tuscany — you can go to areas that feel remote and isolated and relatively undiscovered by tourists. There you can also feel a greater connection to the land and its produce. There are many charming and historic places to stay in this part of the world and my first stop, thanks to a recommendation from my colleague Maria Shollenbarger, is Castello di Vicarello in Southern Tuscany, between Cinigiano and Paganico.

Positioned on the top of a hill, Castello di Vicarello is a 12th-century castle with panoramic views in every direction. The nearest dwellings are mere dots in the distance, and it only takes a few minutes of soaking in the calm of this small nine-room hotel for the stress of highway driving to melt away. I arrive just in time for lunch in the central outdoor courtyard and one of the first things I hear is an Australian accent. A couple, who I later discover are from Sydney, are talking to Bradley Cocks, a hotel consultant who has been working with the Baccheschi Berti family on Castello di Vicarello and who has also lived in Sydney. He shows me around the property, which feels more like a large private home that just happens to have cloistered quarters for house guests.

I’m staying in Suite I Sassi, a spacious separate building with an entire façade of glass sliding doors allowing views over the hills all the way to the Tyrrhenian Sea in the distance. Castello di Vicarello, with its two infinity pools (one conveniently positioned directly in front of my suite) is the sort of hotel where you could happily do nothing but eat, sleep, read and swim for days on end.

The Baccheschi Berti family, however, have devised a range of activities for guests, from cooking classes to helping with the grape and olive harvests, to yoga and meditation. I decide to discover the Maremma region by e-bike and take off with a guide early the next day to avoid the heat. In nearly two hours we barely pass a car on the winding and picturesque roads. In the town of Cinigiano we stop for a coffee. You know that you’re off the beaten track in Italy when the locals come out of their shops to give you that you’re-obviously-not-from-around-here look and when coffee costs one euro (which my guide thinks is expensive).

Cocks maps out a route for me to follow to my next destination that will keep me off the frenetic highways and take me the slightly slower way through winding mountain roads and bucolic villages, to one of Tuscany’s, not to mention Italy’s, most famous hotels, Il Pellicano on the Argentario peninsula, about 35km south of Grosetto.

The drive takes me though stretches of farmland as far as the eye can see, and in the middle of the day with the searing heat outside each village we pass through seems like a ghost town. On some of these roads, the only traffic problems we encounter are slow-moving tractors and their wide loads of hay. The breathtaking medieval hilltop town of Scansano, famous for the Sangiovese-based wine of the same name, Morellino di Scansano, is remarkably free of tourist buses. There are several buildings from the 15th and 16th centuries along the main street, including Palazzo Vaccarecci, which can be identified by the coat of arms on its façade, and the Romanesque church of San Giovanni Battista. Away from the main piazza there are myriad alleyways to wander through, with spectacular panoramic views to be glimpsed from between the buildings. This is literally a place to stop and smell the roses, with trellis after trellis covered in fragrant climbing blooms.

June of this year was the hottest month ever recorded in Europe, and while the Quattroporte’s ventilated seats and air-conditioning (turned to the max) make it comfortable in the car, the idea of a seaside sojourn is suddenly very appealing. It’s an easy drive through the Maremma plains to Porto Ercole on the Argentario peninsula, and from there it’s just a 10-minute meander on the winding and aptly named Via Panoramica to Il Pellicano.

It helps that I’m driving the biggest Maserati in the fleet, but when I arrive at the main entrance to Il Pellicano I get almost royal treatment. I’m staying in one of the villas at the rear of the property. It looks over the resort and out to the sea, and although it comes with a parking space the concierge recommends that “with a car like this I should park the car in underground carpark”. When it is returned two days later the Tuscan dust has been washed off and it’s ready for the next leg of my journey.

Il Pellicano’s 50 rooms and suites are spread throughout several villas covered with bougainvillea and shaded by umbrella pines. The gardens of the resort are strewn with cypress pines and bulging hedges of rosemary. The pool, which is edged in sandstone, is heated seawater and an elevator descends the cliff face to a terraced beach club with a private jetty extending into the crystal-clear sea. The pool and beach club were photographed by Slim Aarons, a regular guest in the ’60s and ’70s and the hotel still exudes a Hollywood jet-set vibe.

It was built by Michael and Patricia Graham, a British aviator and his American socialite wife, as a private love nest. The Grahams eventually started opening their doors to a few of their friends and, as the years passed, the extended circle included politicians, royalty and movie stars. In the late 1970s the hotel was bought by its present owner, Roberto Scio. Today it is overseen by his daughter, Marie-Louise, vice president, group director and creative director of Pellicano hotels, which includes La Posta Vecchia near Rome and the recently opened Mezzatorre Hotel on the island of Ischia (see story at left).

After two nights, it’s time to get back in the now sparkling clean Quattroporte and head to Pellicano’s sister hotel, La Posta Vecchia, a 90-minute drive away. Possibly the only Renaissance palazzo ever built on a beach, the hotel is at Ladispoli, about 38km from the centre of Rome. Legend has it that J Paul Getty tried for years to get the Odescalchi family to sell him their coastal home. Eventually they gave in to him but they kept the adjacent medieval fort. Getty quickly transformed the palazzo into his own private museum, stocking it with tables that once belonged to Caesar and beds that were owned by the Medicis. He also turned one of the reception halls into an indoor swimming pool and it remains to this day (and is far more appealing than the black sand beach below).

After Getty’s grandson was kidnapped in Rome (in 1973), held for ransom and had his ear cut off, the billionaire oil tycoon left Italy and swore never to return. La Posta Vecchia was soon sold to the Scio family — complete with its contents — and they used it as a family beach house before turning it into a hotel.

Once you get to this hotel, you never want to leave. All 19 rooms and suites are spacious and have been uniquely decorated with Renaissance furnishings, paintings, chandeliers and antique tapestries. When Marie-Louise Scio updated the rooms, she kept all the original pieces and just added a few contemporary luxuries such as expansive showers.

It’s hard to believe this seaside hotel isn’t much further from Rome than the city’s Fiumicino airport. After a week behind the wheel of a Maserati, I have developed the driving confidence of a Tuscan. Dropping it in to a Maserati dealership in Rome should be a snap. Wrong. Romans, like their Tuscan neighbours, have no regard for speed limits, but they also rarely observe lane markings, pedestrians, stop signs or merging traffic. It’s every driver for themselves.

The Maserati logo is a trident based on the one in the Fountain of Neptune in Piazza del Nettuno in Bologna. The Maserati brothers adopted it as the emblem for their first car, the Tipo 26. There’s one on the grille of the Quattroporte and the symbol is said to represent strength and vigour – two attributes every driver needs to tackle Roman traffic. The experience goes as badly as I was expecting — a missed turn-off, a six-lane ring road to contend with and an epic traffic jam. But I arrive — guided by Neptune — unscathed. Days later when I drive a friend’s Fiat 500 through the streets of Rome it doesn’t feel nearly as much fun — and nor do I garner anything like the respect I had when I drove a Maserati.

-

ISLAND IN THE DREAM

Capri’s unsung neighbour is suddenly on the radar, thanks to the arrival of one of Italy’s most dynamic tastemakers.

Ischia. Ring a bell? That ancient island floating in the Gulf of Naples, some 30km from its tinier and more famous sister, Capri? Readers will know it primarily, possibly even solely, through literature or film: Ischia is a Patricia Highsmith regular, featured in both the René Clément and Anthony Minghella adaptations of The Talented Mr Ripley. Highsmith’s fictitious 1950s Mongibello – deftly sketched as a louche, shambolic place in the vast unknown below Naples – was represented by Ischia Ponte, the real-life tiny port village in the shadow of the 14th century Castello Aragonese, which crowns a massive rock formation connected to the main island by a 575-year-old causeway. The names Citara and Maronti might instead evoke the long, densely populated beaches where Lenù Greco – the unworldly heroine of Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan quartet of novels – has her literal and figurative horizons momentously expanded at the age of 16.

Ischia is about four times the size of Capri, with six discrete municipalities and a rocky interior whose dense forests are sporadically punctuated by the vivid green of carefully tended vineyards. Having long been the holiday escape of Naples’ lower and middle classes, its summer population hews more popolare than dolce vita. But in this is a certain charm – that

of unadulterated southern Italy, to a degree not commonly found these days. And the island has a long history, easily the equal of Capri’s if less well known, dating back to the 8th century BC, when it was one of the first established colonies of Magna Graecia. In Lacco Ameno, Ischia’s most patrician town, the 18th-century Villa Arbusto harbours a modest but intriguing archaeological museum, and recalls Capri’s ravishing Villa San Michele (albeit in far more modest dimensions). Its thermal spas have been extolled for nearly 3000 years, first by those early Greek colonists and then the Romans who followed them (as well as more recently by Angela Merkel, who purportedly spends a week on Ischia most summers, taking treatments).

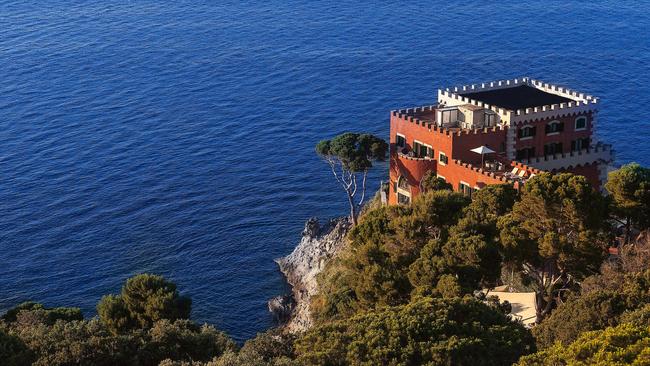

This conflation of high — well, middle — and low that has historically been Ischia’s calling card is shifting, however, thanks in great part to the arrival on its shore of Marie-Louise Sciò, whose micro-collection of Pellicano hotels (see below) now includes Ischia’s 54-room Hotel Mezzatore. Sciò assumed management of the 16th century watchtower-turned-hotel last winter. There was time only for soft renovations before it reopened in April flying the Pelli flag, but between its inherent good attributes — foremost among them probably the island’s prime setting, on a northern promontory surrounded by tranquil woods — and Sciò’s estimable talents for both interior design and social mixology, it has already established a firm foothold on the Mediterranean summer circuit.

The rooms radiate joy and colour, with extravagant Pierre Frey and Manuel Canovas fabrics and Rivolta Carmignani linens mixed into a spare white-on-cream-on-terracotta palette. They are scattered across three floors of the main tower and throughout a handful of bungalows set in the sea pines on the hillside above it. The alfresco Baia restaurant is a study in seaside chic, its teak chairs swathed in a blue Pucci-esque print and its tables laden with maiolica from Caltagirone; the hotel’s small thermal spa, reimagined subtly by Sciò with deep green tiles, potted palms and rattan, strikes the perfect note of understatement. The beach, a terraced affair secluded in a cove below the pool and lined with sky-blue loungers and umbrellas, recalls that of Il Pellicano.

Between the coddling surroundings, private coordinates and sleek, mondane clientele, the temptation to never leave the Mezzatorre’s lovely premises is strong. But that would be to miss a trick, because in and among Ischia’s high-low beachside shops, modern block flats and occasionally ragged roads are addresses worth seeking out. The terrace at Umberto a Mare, for instance; cantilevered out over the sea, dressed in billowing white linens and serving unassailable seafood, it’s the town of Forio’s — and one of Ischia’s — most elegant dinner settings, with a knockout sunset perspective. For an honest, barefoot lunch, make instead for Le Petrelle, reached via a long but worth-it stroll down to the far, far end of Maronti beach.

It’s a blue-painted shack on the sand, in essence, but one that sequesters a kitchen run by two sisters who turn out impeccable pastas alongside tartares and sashimi, served with sweating carafes of the local biancolella white. For history buffs, the labyrinthine Castello Aragonese is a must – now crumbling, deserted and deeply atmospheric, it was once inhabited by more than 2000 souls. Just up the road from the Mezzatorre is La Mortella, the ravishing botanic garden created in the 1950s by two of Ischia’s best-known expatriates, the English composer William Walton and his Argentine wife, Susana.

Lacco Ameno may be Ischia’s most bourgeois town but Sant’Angelo is its most charming; the place to while away the aperitivo hour is the terrace of Dal Pescatore, overlooking the little harbour and the face of Sant’Angelo shearing up out of the water. The views are fine, the air tinged with the salt of the Tyrrhenian, the bougainvillea lush and the welcome warm, if occasionally slightly unpolished. It may never glitter quite like Capri, but Ischia has a glow all its own.

Mezzatorre.it, doubles from €442

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout