Dior’s New Look gets a makeover

The house of Dior – creator of the famously uberfeminine New Look – has embraced a freer expression of womanhood under Maria Grazia Chiuri, its first female creative director.

Feminine vs feminist. It has endured as one of the great false dichotomies of modern womanhood. That the two don’t – in fact shouldn’t – exist in mutual exclusivity seems pretty elementary to a lot of us born after the ’60s, yet the topic somehow continued to be prosecuted across the arc of modern culture until dismayingly recently, from literature to art to film. And, of course – actually, arguably more than anywhere else – in fashion.

But lately the world of fashion looks, and acts, very different. Issues of social disparity – of race, of gender, of indigenous populations, of health and education opportunities – that were long consigned to the periphery of its solipsistic bubble are now key talking points in the dialogue between the industry (which, with an estimated 2020 global value of about $US1.5 trillion, is an economic juggernaut) and its ever younger, and more socially engaged, consumer base. You can chalk this up at least in part to the game-changing clout of social media, with its instantaneous information flow and its cults of personalities who see no conflict in the blending of political opinions with aesthetic ones, from the Jenner sisters to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (among the publications that have noted the phenomenon of female politicians migrating onto the fashion-influencer stage are Elle, Vogue and The New York Times). Whatever the catalysts, the raised voices and altered perceptions have brought about a real sea change in the way the business operates, from goods production to messaging to creative partnerships and collaborations. In 2021, social consciousness has a prime place at the table. Gender parity, racial equality, sustainability – they are fashion now.

A seminal moment in this trajectory: September 30, 2016, the Musée Rodin, and the front row of the Dior Spring Summer 2017 ready-to-wear show. Among the usual suspects – Rihanna, Kate Moss, J-Law – there was one far less congruous name: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, the Nigerian-born writer and MacArthur Genius Grant recipient whose 2014 TEDx talk and long-format essay “We Should All Be Feminists” established her as one of her generation’s preeminent sociopolitical commentators. Ngozi Adichie was, in fact, the guest of honour that day; she had been a primary inspiration for the collection, which was the debut of Dior’s new creative director, Maria Grazia Chiuri – the first woman to helm France’s most venerated fashion house in its 70-plus years of existence.

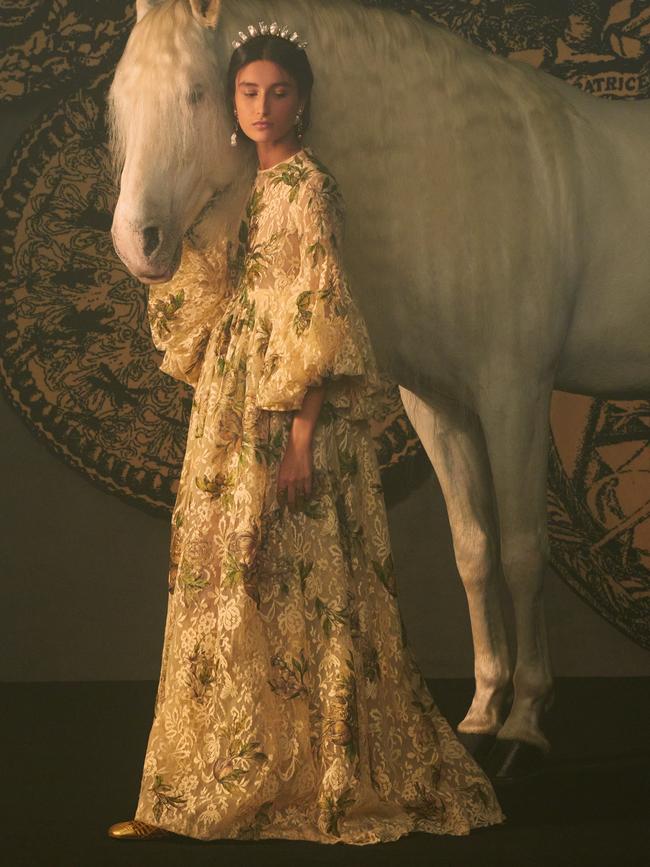

The rest – not least the famous WE SHOULD ALL BE FEMINISTS T-shirt that Chiuri sent down the runway that day and into the annals of bestseller-dom – is fashion history. Part of what made the firmament rumble was that this happened at Dior, which in the hallowed pantheon of couture and ready-to-wear is a sort of institutional byword for uber-femininity. Christian Dior’s New Look was something of a regression even in 1947 when he launched it; padded, embellished, wasp-waisted and full-skirted, it both exaggerated and contained the Female. Through the tenures of subsequent creative directors, from Yves Saint Laurent to John Galliano, it remained a fairly signal point of reference. (Dior is also, it’s worth noting, the prize show horse in the LVMH stables; though the luxury conglomerate famously never discloses individual brand financials, the maison is known to be one of its biggest earners, and is also closest to the heart of chairman Bernard Arnault, who finally succeeded in consolidating control of it in 2017 with a $US13.2 billion investment. So rattling the cage here was a bigger deal than it would have been elsewhere.)

Chiuri has hardly abandoned Dior’s illustrious heritage; but nor is she there just to burnish an incumbent aesthetic or philosophy. It could be said that her 2016 salvo was a sort of mission statement, and the codicils she has since written to the Dior manifesto have been as bold, and as thoughtful. Not to mention resonant: in 2019 her achievements on behalf of one of France’s most vaunted institutions were officially recognised when she was inducted into the Legion d’Honneur; in a minor departure from protocol, her award was presented to her by France’s minister of gender equality.

“Some values are fundamental to my person,” she tells me. “I want to preface [everything else] by saying that. It’s therefore natural for them to be part of my work. My work as a designer is infused with these beliefs naturally. But I’m very aware of the responsibility I have in my role, and the significant [platform] it brings. I feel it’s my duty to use this position to increase the visibility of ideas, projects, and people that match my values – to raise up the voices of other women, with whom I share certain of these ideals.”

Chiuri’s initiatives span every aspect of the Dior world. As one of her first points of order she mandated the almost exclusive use of female photographers to shoot Dior campaigns – Brigitte Niedermair, who had a career retrospective at the 2019 Venice Biennale (and has been a regular collaborator and confidante of Chiuri), is prominent among them. For the third installation of Dior Lady Art, an invitational reinterpretation of the iconic Lady bag, Chiuri conscripted 11 relatively obscure female artists and artisans from around the world, conferring the sort of global exposure (and profit returns) most could otherwise only have dreamt of. She actively researches female makers to contribute to production: these have so far included small textile and embroidery collectives in Nigeria and The Ivory Coast (Cruise 2020), Mumbai (spring Couture 2020), and Puglia (Cruise 2021), where she has family roots. She has invited the likes of art historian Linda Nochlin and feminist artist-educator Judy Chicago to participate in her shows and collections (the former’s seminal 1971 essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”, was distributed at the Spring 2018 ready-to-wear show in a booklet Chiuri had printed for the occasion). And in 2019 she launched a series of recorded one-on-one conversations with fellow creatives, under the heading The Female Gaze, a term borrowed from the feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey.

Speaking to Chiuri about all this, one has the impression she’s slightly wary of the term “feminism” itself – its opacity, its vulnerability to misappropriation, above all its propensity to superficial use. “To me feminism is quite simple: it’s inclusivity,” she says. “It isn’t, it cannot be, exclusive to women. It’s recognising that caring for the entire world entails including women in that care, maybe even with privilege. Of course it can be difficult to communicate a message of sisterhood that’s in keeping with this global vision. But then we have had to adapt ourselves to systems that themselves are not so in keeping with [that kind of] inclusivity – that aren’t really open to that direction, that concept. It’s still, let’s face it, something of a patriarchal mentality that women often [have to] deal with.”

Chiuri’s own formation took place against a middle-class Roman backdrop. (“I think the patriarchy is something very close to me,” she told W in 2018, in reference to having been raised in a country where divorce was only legalised in 1970, and abortion rights first arbitrated four years later. “We try not to feel this reference; but we were born with this reference.”) Her mother, who worked full time as a seamstress, and her father, a military attaché, were liberal-skewing Roman Catholics who – unusually, she notes – always encouraged her in her pursuit of a profession. She describes herself as “a complete tomboy – I was a very boyish girl”, one who later visited London as a teen in the early ’80s and fell hard for punk culture, returning to Rome with shorn hair and a black-heavy wardrobe.

Not long after leaving Rome’s Istituto Europeo di Design (IED) she joined Fendi’s accessories team, where she rapidly made herself indispensable by co-authoring iconic designs, among them the Baguette. Her star rose similarly quickly at Valentino, where she worked with long-time design partner Pierpaolo Piccioli, first as accessories directors – their Rockstud shoe is still a hallmark of the core Valentino offering – and then as co-creative directors. (Piccioli stayed on as sole artistic director when she left for Dior in 2016.)

Chiuri cites the influence of working for the Fendis, fashion’s original matriarchy, as seminal to her formation, in that a powerful female executive was a paradigm she experienced daily. “Anna Fendi would visit all the suppliers herself. They [the five Fendi sisters] were all very involved. We would take the train to Florence together to visit the leather workers and the textiles factories.” She affirms that this helped her when she was transitioning into the far more formal (and staid, and sizeable) environs of Dior. “To me it was a shock how big, and divided, it was,” she says. She realised soon after arriving that her way of leading – collaborative, inquisitive, hands-on, definitively not from the top down – was itself a bit of a shock for the Dior rank and file (and probably some of the top brass, too). “They had a different idea of a creative director,” she says, the seven men in whose footsteps she followed implicitly referred to with a pointed smile.

The woman from whom Chiuri seems to draw the most consistent inspiration these days is her own daughter, 23-year-old Rachele Regini. Regini, who graduated from Goldsmiths in London with a degree in art history (and further studies in gender, media and culture), joined the house as a cultural adviser in 2019. Like her mother, she divides her time between Rome and Paris. Like her mother, she thinks professionally about how to disseminate messages and give women avenues to agency via the Dior brand. But education and proximity to youth culture – she cites the intersection of gender and racial equality as the social issue closest to her own heart – mean that she, more than her mother, is the house’s vanguard in this arena. As the creatives are concepting the season’s themes and designs, Regini is roving the contemporary culture landscape to find the names, faces and ideas that dovetail with the artistic direction.

“The focus on feminism is the fil rouge” for all of them, Regini explains. “Fashion has a huge responsibility in contributing to shaping women’s relationships with their bodies, their image. We aim to offer a representation of femininity that is multi-faceted, that presents women of different social and cultural backgrounds – to encourage collaborations to offer female creatives a strong platform from which to provoke, to create, and to illustrate their ideas concerning femininity.”

“Having a daughter inevitably forces you to ask yourself a range of questions,” Chiuri says. “I’ve always been in a long, close dialogue with Rachele. But today, discussing certain topics with her helps me enormously. Through her studies, but also her very nature, she is so attentive to and always questioning the fundamental issues of feminism, of inclusiveness.”

Chiuri admits to having been to a degree schooled in the 20th and 21st century feminist canon by her daughter. For her part, Regini acknowledges the pleasures, and professional satisfaction, of collaborating with both heroes and new cultural acquaintances: “I have been able to work alongside women I admired at university, and meet women artists I didn’t know beforehand. It is an absolute privilege to be able to see their creative process and to learn how to shape a dialogue between their fields and fashion.”

I ask her which, to her mind, is the most rewarding and resonant statement she and Chiuri have been able to make. “The Chanakya School of Craft in Mumbai,” she replies immediately. “It’s one of the projects I’m most proud of. We helped a local factory”– Chanakya International, which produces legacy embroidery that Chiuri has been working with for years – “to start a school for women to learn the traditional techniques. They gain financial independence from their families and husbands, while mastering an art that has been historically practised only by men.”

More than 100 of these artisans collaborated on production of the Dior Spring 2020 couture presentation. Such events tend to represent the pinnacle of fashion’s rare ether: extravagant set designs, packs of privileged VIPs flown in from the four corners of the Earth, outrageous sums commanded by frocks a single one of which can take months, and multiple sets of les petits mains, to produce. But fashion looked a bit different that day; because there was Chanakya – a story of real empowerment, subtly embedded in all the pageantry, thanks to women with a vision, and a mission.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout