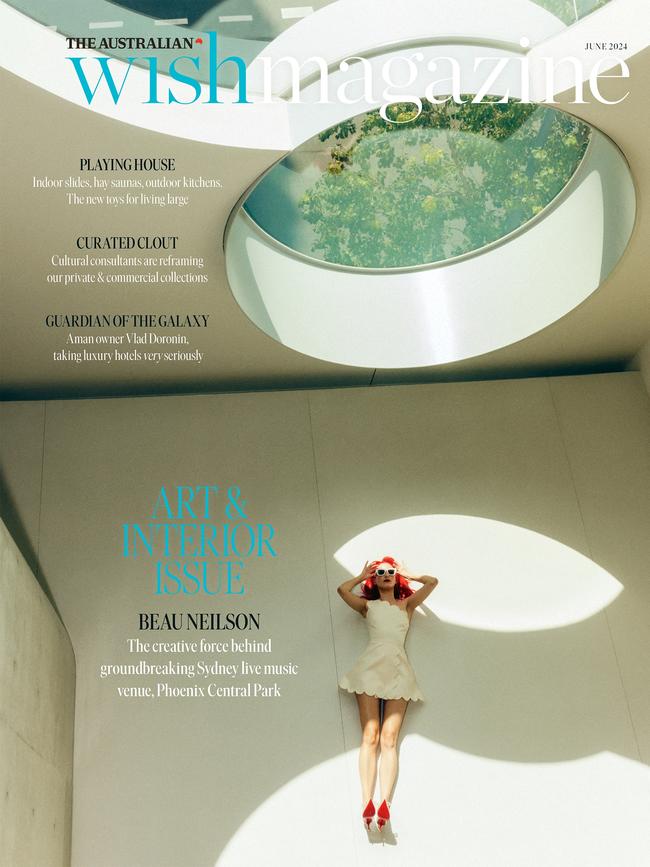

Beau Neilson’s thriving private philanthropic live music venue

Phoenix Central Park is on a mission to encourage boldness, bravery and exploration via a space that democratises the experience for audiences and performers alike.

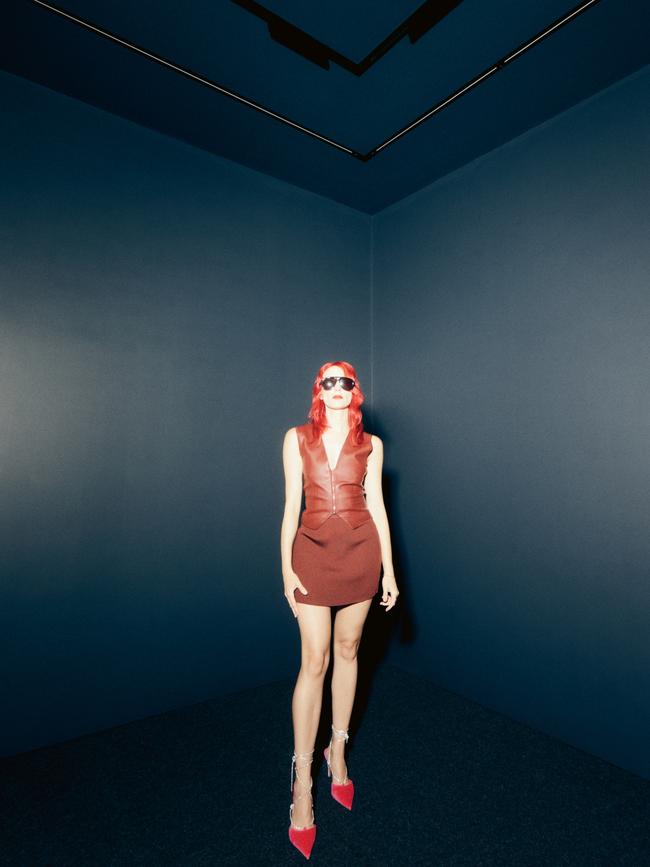

It’s a baking hot early autumn afternoon in Sydney and outside on the streets of inner-city Chippendale people, trees and flowers are wilting in the heat. Inside Phoenix, however, the huge, arresting Durbach Block Jaggers-designed live music space, it is cool and quiet. Phoenix’s creative director and executive producer Beau Neilson is leading me down the spiral staircase onto the subterranean stage and intimate amphitheatre below, to sample a taste of what Phoenix offers.

“It’s very experimental. People have reacted in all sorts of different ways; we had people crying the other night,” Neilson cautions, as she asks her audiovisual team to play the recording of Egyptian multi-instrumentalist, producer and sound artist Zuli, who performed at Phoenix earlier that week. The bespoke blinds close noiselessly above us and we are plunged into darkness as the propulsive beat starts, the music building, transporting and flowing through you until you feel it in your very insides. The lighting pierces the smoke enveloping us, creating an eerie, hallucinatory atmosphere. It is unlike anything I have ever heard before and utterly brilliant.

Welcome to Phoenix Central Park, the brainchild of billionaire philanthropist Judith Neilson, a private initiative that seeks to raise no revenue, offers free tickets and is attracting some of the most cutting-edge musicians from both the contemporary and classical spheres the world and Australia has to offer, hopefully blowing apart audiences’ preconceived notions about what constitutes interesting music.

Phoenix Central Park, which was awarded the prestigious NSW Architecture Medallion in 2020, sits amid what has become something of a mini cultural precinct. The building also houses a multi-level private contemporary art gallery, the work of John Wardle Architects, while nearby is Judith Neilson’s White Rabbit Gallery, a public gallery with free entry established in 2009 to display ever-changing curated exhibitions from her vast collection of contemporary Chinese art, a stone’s throw from the Judith Neilson Institute supporting independent journalism.

Both Judith and daughter Beau and her children also live in the ’hood – Judith in the arresting William Smart-designed home Indigo Slam, and Beau in an elegant and light-filled warehouse conversion.

If it all sounds very Neilson-ville it is, and yet that couldn’t be further from the reality. There is no signage around Phoenix Central Park and one would easily assume it is the sprawling private residence of yet another super-wealthy Sydneysider. Instead, it is the physical embodiment of a grand ambition shared by both Judith and Beau: to provide a beautiful creative space for music that is different, on the fringes, music that pushes us to think outside ourselves and brings us together, hopefully leaving us feeling a little more enlightened and inspired when we leave.

Beau, a graduate lawyer, has been at the helm of Phoenix since 2020. She is driven by a strong social conscience and spent many years working with Anti-Slavery Australia before moving with her former husband and two young children in 2018 to the UK, where she consulted to various not-for-profit organisations in the youth, arts and sports space, reviewing strategy, business plans and partnerships.

Upon their return to Sydney, she took over the programming and creative direction of Phoenix from Judith. The former martial arts warehouse – it burnt down before being reborn under Judith’s vision of Gesamtkunstwerk, the German concept of a “total work of art” – was already playing host to chamber and classical music ensembles on a casual, invite-only basis. Of course, the pandemic decimated the live music scene and Phoenix pivoted to producing and streaming intimate filmed music series that enabled small numbers of musicians to perform live together in the space, ensuring there was at least some income for those taking part.

It wasn’t until 2021 that Neilson could really sink her teeth into live programming and she was determined to diversify the audiences and types of music being presented. “Judith’s vision was that Phoenix would be an architectural icon that would encourage bold, creative risk-taking, particularly musical risk-taking,” she says.

“The way music streaming platforms work is to give you an illusion of discovery, meanwhile your existing tastes are just being reinforced. I think it’s important for people to be braver, and that happens best with live music when you’re experiencing something in its fullness, with other people.”

Neilson’s team of four are self-proclaimed “show monsters”, constantly attending live gigs and fielding pitches from agents, managers and artists. They look for interesting collaborations, music that is distinct and artists who perhaps don’t fit their regular programming genres of classical, experimental and jazz.

“I like things that are a bit different and on the fringe because if it’s in the middle it’s already happening and that’s great, but we don’t need to replicate it. It’s about what’s different, what pushes us to think, feel or see differently. And that’s the philosophy around Phoenix,” says Neilson.

“I also think there’s a way we can promote young talent and support them so they feel brave enough to get the attention they deserve.”

It would appear the public has taken note and is responding. Performances are held twice weekly, two shows a night, at an efficient 45 minutes. “I think 45 minutes is enough to enjoy something, be present, and invest in something you might otherwise be cautious committing to,” Neilson explains. Capacity is typically 150 people per show and most shows attract about 1000 entrants in the ticket ballot organised by custom-built software. To date there has been 180,000 applications for the 50,000 free tickets available for all 174 acts, who hail from countries including Egypt, Belgium, Angola, the UK, Nigeria and, of course, Australia. The most popular performer so far – UK electronic musician Jon Hopkins – attracted 3000 applicants, “a beautiful show, Music as Psychedelic Therapy, with the smallest capacity unfortunately as people were encouraged to lie on the floor”.

Neilson is happily out five, six, often seven nights a week during the times her children are with their father, for what she describes as her “full-time-plus job”.

“There are late nights involved, so much of the connection-making and research is after hours. You don’t so much have the work/social life/hobby distinction; they become one and the same,” she says, adding, “It’s pretty wonderful, I’m very, very lucky.” Both her children enjoy attending shows, despite the fact her son, aged six at the time, refused to come until he’d heard and approved the sound check. “I told him that wasn’t how other people decided to see a show, but that I appreciated his perspective,” Neilson says with a laugh.

With Neilson it really does seem to be a vocation, not a job. She is the president of the Chippendale Collective, a business development entity supported by Investment NSW that aims to create a more vibrant Sydney. “That’s been a wonderful opportunity to meet local businesses and hear what they’re doing and see how we can share our knowledge and encourage visitation. Community is a big part of the game.”

At the time we meet, she is in the midst of producing the Biennale of Sydney’s inaugural live music program, at the refurbished former White Bay Power Station. “It’s a significant moment for Sydney, to see how we can reinvent these disused spaces so they can be cornerstones of cultural infrastructure, not apartments,” she says. Phoenix was also instrumental in hosting live music during the first SXSW Sydney last year, with artists from the Northern Territory, The Philippines, the US and Indonesia.

Season XII, Phoenix’s 12th quarterly season, features local female post-punk rock band Body Type (recent support act for the Foo Fighters), Denmark-born London-based experimental music composer, violist and songwriter Astrid Sonne, and Waakya, the cross-cultural collaboration between Yolngu songman Daniel Wilfred, his brother and yidaki player David and electro-acoustic musicians Martin Ng and Ben Carey.

Neilson’s outlook is unsurprising when you consider her background. She had an undeniably privileged upbringing, but it was an upbringing that was also culturally rich. She and her older sister Paris grew up in Sydney as first-generation Australians to their South African-born father Kerr Neilson, who co-founded the billion-dollar company Platinum Asset Management, and Zimbabwean-born Judith whose background in and ongoing commitment to the visual arts, music and social impact was a strong influence. The couple migrated to Australia in 1983, divorcing in 2015.

Today, both Paris and Beau sit on the committee of The Neilson Foundation, supporting the arts and charities working towards social cohesion including Taldumande Youth Services and Refugee Advice & Casework Service. The foundation has disbursed more than $158 million since its inception. Neilson is also a trustee of the Powerhouse Museum and a former director of Sydney Dance Company.

“We always understood the importance of contributing to the community, but it has to be part of a larger, broader structure where a person is actively involved in producing these things and helping people, not just at the end of a bank cheque. That’s always been our philosophy,” Neilson says. “I’ve seen with Phoenix the power music can have for the artists, to encourage them to explore. We need artists and creativity to move forward. These are the things that make us most human.”

Phoenix Central Park’s Season XII runs until June 27.

This story is from the June issue of WISH.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout