Who killed Marea Yann? Police review unsolved 2003 murder case

The unsolved murder of Marea Yann in 2003 haunts her family – and the cops who investigated it. Will this cold case finally be cracked?

May 24, 2021. Victoria Police homicide squad officer-in-charge Tim Day is in the studio with Melbourne radio host Neil Mitchell, talking about a new online “cold case hub”. The veteran cop tells Mitchell advances in forensic science and technology can only do so much. He wants the public to go on the police website to help solve selected murders from years and in some cases decades ago. “It’s about fellow human beings providing us with the information that we need. People can’t hold secrets their entire lives,” he says. Eleven minutes into the interview, Mitchell is about to wrap things up when he puts Day on the spot with one more question: “Is there one, in all the ones you’ve dealt with, that you’d particularly like to see solved?”

“There’s one particular one from 2003 that I’d like to solve, from Juliet Crescent in Healesville,” Day replies. “That’s one that always comes back to me, that yeah, you’d like to think you’ve done everything that you can, but, yeah. Before I retire, that’s one I’d like to solve.” Mitchell is paying attention: “Who is the victim?” Day: “That’s Marea Yann.” Mitchell: “Why? Why does that one stay with you?” Day: “I think that it’s solvable.”

It was an unscripted response. Five cases had been chosen for the hub’s launch, and the haunting murder of 69-year-old Marea Yann wasn’t one of them. Marea, an adored mother, nonna, widow, friend and op shop volunteer, had been bludgeoned to death in a chair in her home. Her killer had loomed over her, probably from behind, and struck her 22 times in the head. The unidentified murder weapon was something solid and heavy, like an iron bar or the blunt end of an axe. She had no defensive wounds, meaning whoever did this struck with no or little warning, and made sure to finish the job. Day had been the lead investigator.

Most of Mitchell’s listeners probably didn’t give another thought to the brief exchange, but to a select group it had profound meaning. At the end of a busy day’s work, Marea’s son Jeff looked at his mobile phone and found the screen filled with missed calls and messages from family and friends. Jeff phoned his sister Ronda, who had already heard the segment, and they both wept over the phone. Marea’s sister, Deanne Green, 89, had heard it too and shared it on Facebook. There was an immediate sense it was the light they had been waiting for in a 13-year tunnel, stretching all the way back to 2008, when a jury found Marea’s son-in-law, Joseph “James” Chuks Unumadu, the husband of her daughter Pauline, not guilty of her murder.

Jeff Yann, a landscape gardener and keen surfer who lives at Mount Martha on Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula, still gets goosebumps thinking about Day’s off-the-cuff comments. There are more than 200 cold cases on the homicide squad’s books. What had made Marea pop into the detective’s mind? Jeff, 63, says it felt like divine intervention. “I was in shock. It was so confronting. Mum’s case to us was almost over and done with, but all of a sudden there was a pulse,” he says. “There was a pulse for the first time in all this time. Then I listened to it over and over again.”

Words were one thing, but without the family knowing at the time, Day had already quietly ordered a review of Marea’s murder by a cold case investigator, Detective Senior Constable Caitlin Jones. Speaking to The Weekend Australian Magazine in early August, the two detectives confirm it is the first time the case has been reviewed since the 2008 acquittal.

Day explains that while all unsolved cases are important, he mentioned Marea “because it was one that I did early in my career as a homicide squad detective and it’s one that got away on us”. Police looked at about 20 persons of interest through the course of their original investigation, and he wants to make it clear the new inquiry will be an objective look at the facts. Jones is free to go down any path she sees fit. “The key to this is the fresh set of eyes,” Day says.

Marea Bambina Alice Tancredi was born on November 21, 1933, in a remote farmhouse in Wangrabelle, Victoria, with the Genoa River raging in flood. Her migrant Italian father arrived hours later to find his exhausted Australian-born wife, a weak newborn and two distressed little girls – Marea’s sisters Deanne, then two, and Carmela, one. “Marea arrived with the karma of drama, a characteristic she still has today,” Deanne recalled in a speech at Marea’s 60th, captured on camera. Their parents had three more children and raised them in Preston, in Melbourne’s north.

At 17, Marea married Ronald Yann, and they had three children – Ronda, Jeff and Pauline. Ronald became a teacher, and then the happily married couple retired to a hobby farm in Acheron, 120km northeast of Melbourne. In home videos, Marea showed off a pantry brimming with bottles of preserved fruits and jams, and a room lined with her dazzling collection of heels. “Aren’t they gorgeous? They’re my disco shoes,” she says in one recording, holding up a sparkling red pair.

In 1984, the Yanns were rocked by Ron’s death in his 50s from a heart attack. Marea stayed on the farm, where nine years later family and friends gathered from all corners for her 60th. There were tents, a cake with white icing, coal-roasted lamb and towers of plates. Her sister Deanne says in her speech that Marea’s anthem in her youth was Vera Lynn’s It’s a Lovely Day Tomorrow with its lyrics:

Just forget your troubles and learn to say

Tomorrow is a lovely day.

It was a philosophy Marea still lived by, Deanne said. Four years later, in 1997, Marea said goodbye to the farm where her beloved husband’s ashes were buried and moved to the bluestone cottage she had bought in Juliet Crescent, Healesville, in the Yarra Valley. It was a peaceful, secluded location, set on 0.65ha of land. Deanne was just 15 minutes away in Yarra Glen, and sister Carmela would move to Healesville three years later. Marea found a new purpose, taking over the East End Op Shop and turning it into a thriving venture. Her time was all donated, the thrift store raising money for the local Living & Learning Centre. She quickly made firm friends with staff and customers, who became witnesses to the traumatic final months of her life.

The last time Marea had most of her family together was Christmas 2002, her house filled with mouthwatering aromas from the kitchen. Everyone was taking their seats for lunch when they noticed six extra plates, each piled with turkey and ham and all the trimmings. Marea said the surplus meals were for “the boys”, a group of men from a halfway house she knew through the op shop. Ordering Ronda’s husband, Maurice Chagoury, to load the plates into his car, Marea hopped into the front passenger seat. They drove off to deliver the feast, while the rest of the family sat at the table, stomachs growling. That was Marea. Thoughtful, generous to a fault, and for all those things and more, dearly loved.

At 8.15am on Tuesday, September 30, 2003, gardener Matthew Clifton drove up Marea Yann’s steep driveway and parked. Clifton had been transforming the big yard into a sanctuary for birds and, as usual on his arrival, he tapped on the kitchen window. Marea, living alone, would typically shout a greeting. This time, there was no reply. Clifton busied himself with odd jobs around the pool until he needed Marea’s call on which roses to plant to finish a garden bed. Returning to the house, he found the front security door slightly ajar and, behind it, the wooden door unlocked. He took off his boots and walked inside, calling Marea’s name. Oddly, her purse was lying open on the kitchen floor.

Looking around, he saw the television was on, then spotted Marea in a chair. From a distance, she looked asleep. When he stepped closer, stopping just a foot away, the horrific reality washed over him. He backed away in shock. Just as he got to the door, her friend Janet Bridgart drove up the driveway. “Someone has killed Marea,” Clifton told her. “I think we need help.”

Tim Day was on call with his homicide squad crew and went to the house just after midday. He was then a detective senior constable and had been in the squad for three years. Aside from the blood on and around the chair where Marea’s body was found, there were splatters on the walls, the fireplace, a chest, dresser, ornaments and silverware. Some of the stains were from the impact of the blows, others from the repetitive swing of the unknown weapon. All pointed to Marea being killed in the chair. The purse on the floor was also stained with blood, having been rifled through or possibly staged to look that way after the murder.

Marea’s daughter Ronda had been the last to speak to her, in a half-hour phone call ending at 8.07pm on Monday, the night before. Ronda had been at her home at Marcus Beach on Queensland’s Sunshine Coast and could hear the television in the background on the other end of the line.

Remove the violence and it was such an ordinary scene. A woman seated, seemingly watching television. Small clues hinted at a slightly different picture. Marea was in her club chair, the one she usually sat in to talk to visitors. When she watched TV, her habit was to use a different chair, a recliner. Another habit was to light a fire if she wanted someone to stay longer – her fireplace was set but not lit. The TV volume was turned low, the way it would have been if she had a guest, and there were no signs of forced entry. Wearing a red top and sweater, black slacks, socks and slip-on shoes, with a cardigan covering her knees, she was not yet dressed for bed. She had on a silver watch, gold and jade earrings and fine gold necklace. A small gold crucifix was no match for the evil that engulfed her.

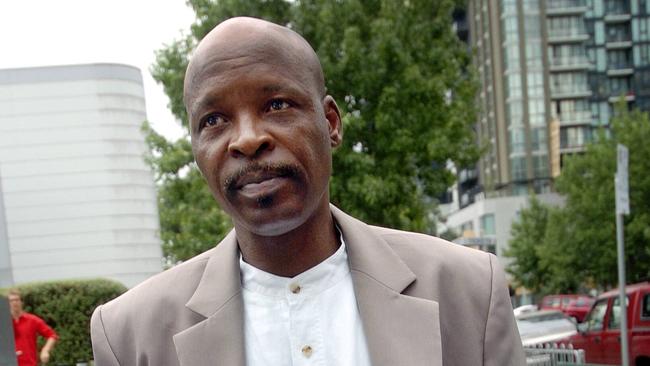

In subsequent investigations, Day and his fellowinvestigators discovered the Yann family was in turmoil in the leadup to the murder. Marea’s daughter Pauline had separated from her husband, James Unumadu, but he was refusing to accept the marriage was over. Marea was in the thick of it, dealing with the fallout of his purported suicide attempts, stalking and threats. Marea had been James’s greatest supporter. In his statement to police he said she was his “number one ticket holder”, and that he always called her “mum”. But she had been backing her daughter’s attempts to end the marriage, and although he has always maintained his innocence, James soon became a person of interest in the murder and was subsequently charged.

The later trial would be told that just over three weeks before she was killed, Marea had sworn an affidavit in support of Pauline’s property settlement claim against James in the Family Court. In the document, Marea stated that although she was fond of James and had a loving relationship with him, his behaviour towards Pauline had been of significant concern and there had been numerous incidents that had caused her daughter distress. James was fixated on a belief Pauline was “having affairs all over the place”, including with her former boss, she said in the affidavit.

Marea made many other comments that were of interest to investigators, and that were included in the police brief of evidence for an inquest into her death, but were not used at the trial. There had been a burglary at Pauline’s new apartment and along with antiques, furniture, personal documents and other valuable and sentimental items stolen, one piece of missing property stood out – a framed photograph of Pauline’s former boss, lawyer Dominic Calabro, hidden in clothing in a drawer. The picture frame was allegedly left on a dressing table with the photograph missing. Marea had said she did not believe James’ denials of being involved and phoned him to confront him about the burglary. He subsequently drove to Healesville, collected her, then handed her a phone. The person on the other end said he was “Ba Ba”, a witchdoctor in Nigeria, that he had received a photograph from James and had put a voodoo curse on Dominic, Marea claimed.

According to her sister Carmela’s separate statement to police, Marea was terrified of what the witchdoctor would do to her family or Dominic, having been told in the phone call that something was going to happen in seven days. A police summary prepared for the inquest says Marea was murdered seven weeks after the witchdoctor call.

Born in Ikire, Nigeria, James migrated to Australia as a 19-year-old in 1976 and started a relationship with Pauline five years later. They married in 1990. Pauline would tell police that despite his claims to the contrary, James did believe in witchdoctors, an intrinsic part of Nigerian culture.

According to the inquest brief of evidence, Marea also claimed James had threatened to cut Dominic’s throat from ear to ear. “I have lost everything. I have got nothing to lose. I don’t care if I end up in jail. Nobody is going to win out of this one,” he allegedly told her. James was “a manipulative and dishonest person who finds it very easy to lie and has done so in the past”, she claimed.

The coroner would also be told that a few months before their separation, James allegedly warned his wife: “If you ever leave, I’ll find you and I’ll kill you, but don’t worry, I’ll make it quick.”

It fell to Jeff Yann to formally identify his mother’s body for police. On the night his mum was murdered he had been to dinner with friends, then they returned home to watch a video with his girlfriend Sue and her daughter. Jeff told investigators that James and Pauline’s turbulent relationship had divided the family, and that on one occasion in April that year, Marea said she herself was manhandled by James. He said that as a result he confronted him, resulting in James wielding a knife and Jeff a shovel. Police were called and Pauline sided with James at the time. In Jeff’s eyes the tense armed standoff was a key moment that should have featured at the trial, but didn’t.

Another witness, Patsy Miller, told police she was browsing in the Healesville op shop when she overheard Marea in a heated phone call. Marea hung up, cursing, and said her son-in-law had just threatened to kill her if she didn’t stop interfering in his marriage, Miller said. After legal argument, this alleged threat to kill was excluded from James’ trial too. The jury did hear from Lynn Chen, a Yann family friend who became a confidante of James. Chen said that in the weeks before Marea’s murder, James was in a rage and said he was going to “get” his mother-in-law. Chen said she told him not to do anything stupid, but he said he had to protect himself. James denied ever threatening, intimidating or harming Marea and said he was home alone in Frankston the night she was murdered. At the trial, police said he did not use his phone from 5.52pm until 11.15pm, more than enough time to drive the 80km to Healesville, kill Marea, and return.

Day estimates he had been to about 50 crime scenes, a number of them homicides, before Marea’s murder. The first file he picked up at the squad was a cold case, the 1982 rape and murder of six-year-old Bonnie Clarke in her home in Northcote, Melbourne. Day reviewed Bonnie’s murder in 2001 with fellow homicide detective Ron Iddles and solved it, identifying the killer as a former boarder at her home. When Marea was murdered, Iddles was Day’s crew leader and oversaw the investigation.

The inquest into Marea’s death was held in Melbourne in February 2006. Called to give evidence on the second and final day, Pauline was defensive of James and critical of detectives, accusing them of failing to take statements from people who didn’t fit their line of investigation. Her mother was “never ever” in fear for her own life with James, she said. “Never did James ever bash or rape me. I want to make that clear today,” she said. “He did ridiculous things, taking my car keys, keeping me locked in the house, and he would hold me down or things like that but never, under any circumstances did he ever bash me.”

Iddles, next in the witness box, rejected the allegations of tunnel vision. Jeff Yann had initially been considered a person of interest, along with up to 18 other people Marea had either assisted, had worked for her or that she had given money to, the detective said. “All of the people nominated have been eliminated and have alibis. There is only one person in this inquiry who remained a suspect and that’s James Unumadu,” he said.

The same day, James’s friend Andrea King told Day and Iddles that about 10 days after the murder he had confessed to her that he had killed Marea. The detectives arrested James just under a week later, before the coroner could deliver findings, and charged him with the murder of his mother-in-law.

Iddles would leave the homicide squad in 2014 with a 95 per cent arrest rate and 99 per cent conviction rate from 320 murders. Marea Yann is one of the rare exceptions. “We’re the one per cent who just didn’t get there,’’ says Marea’s daughter, Ronda, now 66. “Some people never get a chance to bring anything to trial, they don’t have a body, they don’t have a suspect, they don’t have anything, and their lives are in limbo forever. But there’s another very small minority of people like us who go the full hog, if you like, and at the end of it, have nothing. It’s like she has been just swept away. That’s how we all felt, that it came to nothing, it is nothing, and I just can’t really let it go at all.”

The trial of James Unumadu began on January30, 2008. It was held in the Supreme Court in Geelong, due to court renovations in Melbourne. Marea’s family noted the glaring absence of media from the proceedings; while gangland killings were lavished with attention, her life seemed somehow diminished. As Jeff puts it: “That white trash mafia got more coverage than our dear old mum.”

Crown prosecutor Mark Dean told the jury the circumstantial evidence pointed to a planned killing, carried out with a great deal of care and attention, after James made two dry runs to the house in previous weeks. The killer was invited in, engaged Marea in conversation and attacked her suddenly and with great force. There was nothing to indicate a burglary, the purse on the floor a deliberate red herring. At the time, the accused’s wife, Pauline, had moved out of the matrimonial home in Frankston and had started a new relationship, Dean said. The accused killed his mother-in-law because he believed she stood in the way of his attempts to reconcile with his wife, he said.

During the two-week trial the defence cast doubts on the alleged confession, suggesting it was an attempt to collect a $100,000 police reward. James barely knew Andrea King and it defied belief he would confess to her, said his counsel Mark Rochford. “There’s no forensic evidence, there’s no fingerprints, there’s no eyewitness,” Rochford said. The jury returned with its verdict after deliberating for just five hours. Marea’s family sat in the court in silence as it was delivered, Justice Betty King having made it clear she would not tolerate outbursts of emotion in her court. “This isn’t a victory or defeat for anyone,” the judge said. “It ought not ever be the subject of either grief or triumph.”

To this day James denies involvement in Marea’s murder. “For years I was persecuted for a vile murder I did not commit,” he says by text. “I spent two years of my life in remand, while the police and members of family smeared my name. On Google my name remains as the suspect. I am innocent and police needed to look elsewhere but didn’t.”

Jeff, Ronda and other family members have not been able to shake overwhelming disappointment in the trial, and the denial of what they considered to be key facts from the jury. They say they felt they had been gagged, unable to give proper context to events only they had lived through.

Marea’s sister Deanne was so distraught she walked into her yard in 40-degree heat and dug a giant hole. “I just wanted to die and bury myself,” she says. “I thought, ‘I’ll pull all this dirt in on top of myself and I’ll die.’ And I could have done it, I was that low.” The space is now a waterfall and memorial to Marea. Carmela died in February last year, having never seen justice for her sister.

Pauline, 60, who remains in a committed relationship with her former boss Calabro, is still critical of the police investigation and says there wasn’t enough evidence to charge her former husband. Pauline wants police to investigate others, such as the many troubled men her kind-hearted mother helped out. Ronda and Jeff say that for many years they could not talk to Pauline about the murder without it descending into bitter argument. In recent months there has been a shift. “We’re talking about it for the first time and that’s got to be a good thing,” says Jeff.

The one thing they all agree on is that Marea deserves better than being forgotten. Jeff also wants a resolution for the next generation, including his daughter Esther, 27, whose experiences of her family’s suffering has led her to study criminology at Deakin University. “Mum represented love and human compassion,” he says. “What would I like? I’d like to think that I can look at that photo of Mum on the wall and go, ‘You’re at rest now’.”

Caitlin Jones, the new investigator, is starting from scratch. Any of the 20 persons of interest including James could be reconsidered, and new leads will be looked at. Three years after James was acquitted, Victoria reformed its double jeopardy laws to allow a person to be charged twice with the same crime if new and compelling evidence emerges. Jones is sifting through boxes of evidence retrieved from police archives. “It is basically in our eyes an unsolved investigation,” Jones says. “So we put all the past behind us. We’re not bound at all by what’s happened in the past investigation, and in fact we like to work freely from it.”

Pauline is elated but wary about the police review, while for Jeff and Ronda it has brought relief. Finally, there might be a chance of a resolution. Someone must have information that can solve the murder, and just has to come forward. They keep waiting for that day. As Vera Lynn would say, tomorrow is a lovely day.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout