Susan Bryant speaks out on her husband Andrew’s suicide

When her husband — a brilliant doctor — took his own life, Susan Bryant got tired of explaining. So she did the unthinkable.

The last few days had been nightmarish and Susan Bryant was tired of explaining. She decided to write an email to try to explain the inexplicable. The words came to her in a rush, powered by grief, anger and frustration, as well as a desire for the cause of her husband’s death to be known, not covered up. It was a Saturday evening in early May and before she travelled across town for a family dinner, she sat in the study inside the beautiful home on the hill she had shared for 25 years with a brilliant gastroenterologist named Dr Andrew Bryant. Her first instinct was to say sorry.

“I apologise for the group email but I wanted to thank those of you who have been so kind with your messages and thoughts over the last three days,” she typed. “Apologies also for the length of this email but it’s important to me to let you know the circumstances of Andrew’s death. Some of you may not yet know that Andrew took his own life, in his office, on Thursday morning.”

The family’s beloved white dog lay on the floor beside her in the study, while a cat was curled near her feet. Andrew had not suffered from depression before, she wrote, but his mood had been flat during Easter and he had been sleeping poorly because he had been called in to see public hospital patients every night of the previous week. She wrote that because of these long hours — not unusual for an on-call specialist — he had missed every dinner at home that week, including one to celebrate his son’s birthday. “In retrospect, the signs were all there,” she wrote, then chided herself. “But I didn’t see it coming. He was a doctor; he was surrounded by health professionals every day; both his parents were psychiatrists; two of his brothers are doctors; his sister is a psychiatric nurse — and none of them saw it coming either.”

Susan addressed the email to 15 colleagues at the law firm where she works in central Brisbane, and she hoped that it would help them understand why her daughter had phoned on Thursday morning to briefly explain why her mother would need some time off. “I don’t want it to be a secret that Andrew committed suicide,” she wrote. “If more people talked about what leads to suicide, if people didn’t talk about it as if it was shameful, if people understood how easily and quickly depression can take over, then there might be fewer deaths.”

Together, they brought four children into this world and they all still live under the same roof. “His four children and I are not ashamed of how he died,” she wrote. Susan knew that her children felt this way, but she double-checked with them before she sent the email, and before the five of them left the family home to visit the Bryants in Paddington, a few suburbs over. One by one, her children came into the study and read the email over her shoulder. They saw no problem with it. She ended her letter with the spark of an idea; a glimmer of hope. “So please, forward this email on to anyone in the Wilston community who has asked how he died, anyone at all who might want to know, or anyone you think it may help.” It took her about five minutes to write. She sent it at 5.45pm on Saturday, May 6, and then she went to be with Andrew’s family. The next afternoon, Susan thought that a few of her close friends and neighbours might like to read the message. And so, at 2pm on the Sunday, she passed it on to another five people who live in the inner north suburb of Wilston. When two of her children asked if they could share the email on Facebook, she said yes, because she thought that it might help their friends understand what had happened, too.

Dr Andrew Bryant (Brisbane gastroenterologist) took his own life in his office. His wife wrote this. Please share. pic.twitter.com/VD11rBZUeT

— Dr Eric Levi FRACS (@DrEricLevi) 9 May 2017

Within a few days, her words had been read by hundreds of thousands of people around the world. Her email was republished and discussed online and off; both inside and outside the medical profession. It was as though she had shot a flare skyward on a dark night, and suddenly, she found herself surrounded by strangers who were drawn to the distress signal.

People responded to her honesty with their own. They wrote to her with deep, dark secrets and confessions, some of which they dared not speak aloud. She gathered their letters and cards in a large basket that sits in the centre of her kitchen bench, while hundreds more notes piled into her email inbox. Writing to her helped them. She did not know it when she wrote the email, but they needed Susan Bryant then, and they need her now.

Dearest Susan, that is perhaps the most honest and heart wrenching email I’ve ever read … Depression and suicide are both realities of the human condition, in my opinion. My grandfather committed suicide, and it was something as children that we were forbidden to share outside of the family. To this day, I don’t understand this.

They met while they were both studying at the University of Queensland. He was a lanky thing back then but he made an impression at a group dinner where he put away enormous amounts of food — including everyone’s leftovers. He took her to see Simon and Garfunkel at Lang Park the day after Valentine’s Day 1983. He wasn’t into grand romantic gestures. He had no ring when he proposed to her on July 4, 1988, a date he would later jokingly describe as his “loss of Independence Day”. They married later that year on December 17.

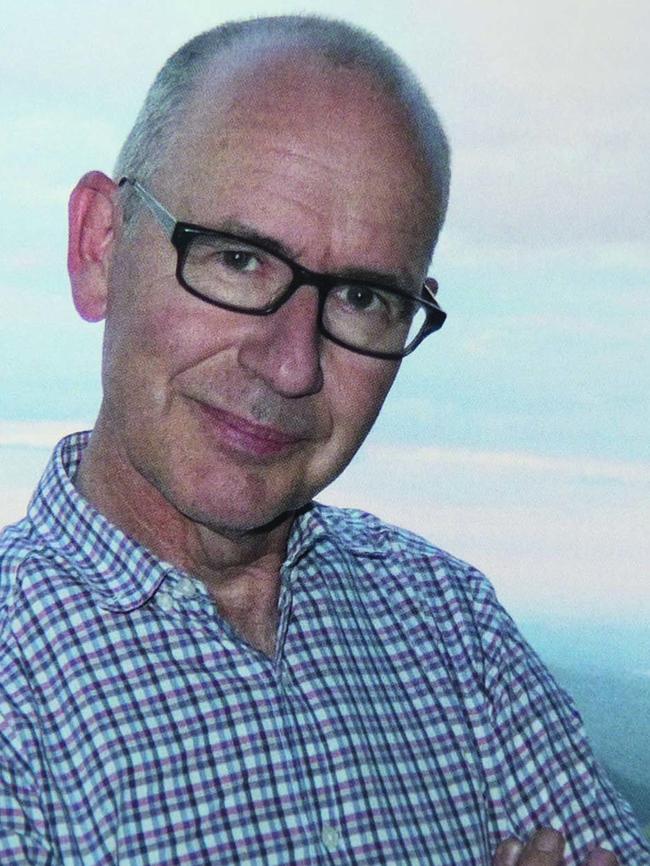

Andrew was exceptionally clever, even among the very bright sparks who studied medicine. Across two decades, he gathered hundreds of patients while gaining a reputation as a compassionate clinician who felt deeply for those in his care. He sang in the UQ Medical Choir, reached the rank of Wing Commander in the Air Force Reserve, and regularly invited his family and friends to all manner of arts and cultural events, even if his workload meant he fell asleep as soon as he sat in a dark theatre.

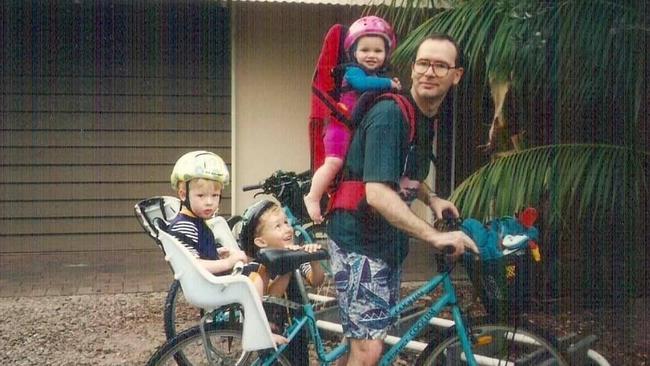

He was the second eldest of seven siblings and knew what to expect when it came to having kids. He was a hands-on father, and when their children were very young he would give his wife blissful weekend breaks by taking them away camping. They would return on Sunday bursting with joy at the glorious time spent with their do-it-all Dad.

Andrew loved cycling and bushwalking and travel. On walking holidays in Tasmania, Bhutan, Japan and Sri Lanka with a few Wilston neighbours, he’d earned the nickname of Mr Nerdy Pants because of his talent for recalling obscure facts.

One of the few areas in which he was not skilled was in sharing his inner burdens. He never complained. He might have framed this trait in terms of resilience or independence, but there were times when his inability to admit injury or weakness troubled his wife. In 2010, he came off his bicycle while crossing a railway track. He broke his scapula and several ribs, and punctured a lung. When he phoned her after the accident he made no mention of these injuries but apologised that he would not be able to pick up fresh bread on the way home.

He was always upset when any of his patients died, but was unusually distressed at a death that occurred on a Tuesday in early May. His secretary overheard him talking about it on the phone, in tears, and Susan thought his distress must have been compounded by his lack of sleep.

Two days later, Andrew was already awake when Susan’s alarm went off at 5.10am on Thursday. He was shaving in the bathroom and she took that as a sign he wouldn’t be joining her at yoga. Still, she ducked in to ask him. He said he was too busy. He looked tired and stressed. She asked if he would be home for dinner, and he said yes. Because he had shaving foam on his face, she kissed him on the shoulder and said she would see him that night.

When she returned from yoga — which was cancelled because the instructor had slept in — around 5.45am, he had already left.

Andrew arrived early at his rooms on the second floor of St Andrew’s Place, Spring Hill. He turned on the lights, locked the door, paid some office bills for stationery, then ended his life. He did not leave a note. His secretary found him soon after arriving at 8.30am. A resuscitation team summoned from the nearby hospital could not revive him. Andrew Bryant died on May 4, 2017, aged 54.

Dear Mrs Bryant, I felt compelled to write to you after learning of the tragedy of your husband’s suicide … Sadly, we have a lot in common. Like Andrew, my husband was a gastroenterologist. And like you, we have four children. By April, as his depression deepened, his sleep medications were having less effect and his sleep was suffering again … He never came home. He took his own life sometime that morning. He was 50 years old … I don’t intend to upset you with this letter, but the similarities were too uncanny to ignore. And I admire the way you have been able to communicate such an important message so soon after your husband’s suicide.

Her three sons were still in their pyjamas when she arrived home to find two police officers in her lounge room just before 11am. She saw that her eldest son, John, 25, was crying and as soon as he said two words — “It’s Dad” — Susan knew that he was dead, and she knew how he died. She compares this sensation to the image of dominoes falling, where the flatness of the last few weeks of his life suddenly made perfect, terrible sense.

Her daughter Charlotte arrived home from the nearby dog park, and as Susan shared the worst news of their lives her first instinct was to say sorry. She apologised to her children for not seeing the signs, and they rightly told her that it was not her fault. She told herself that she was a stupid, stupid woman for never once considering the word depression in those last few weeks of his life. Her younger brother was 25 when he died by suicide in 1993, but in far different circumstances: he had schizophrenia and suffered psychotic episodes, and had stopped taking medication in the weeks leading up to his death.

News travels quickly within medical circles and Susan started receiving messages within an hour. Medical people do not mince words, and many of them already knew his cause of death. But when she listened to her daughter calling one of her law firm colleagues to say that she wouldn’t be at work today, she started to think about telling people how he had died. She didn’t want to keep it a secret.

Later, alone with her husband one last time in the big chapel attached to the funeral home, she felt a strong urge to kick the stand on which his coffin lay. She stood over his body and she did not cry. Instead, she whispered to herself: you stupid, stupid man. Her overwhelming emotions were anger and frustration. She wondered why he didn’t talk to her before doing what he did. If he had said something to her about how he was feeling, it would have been so easy for her — and the dozens of medical professionals in his life — to have helped him.

She has so many questions about what was going through that encyclopaedic brain of his leading up to his final act. It frustrates her that these questions can never be answered. Susan’s children have noticed anger spilling out of her since he died, aimed in the direction of minor things that usually wouldn’t bother her. A counsellor said something that resonated: she doesn’t need any conflict at the moment. When she feels her anger rising, she repeats that simple phrase to herself, and she feels the anger subside.

Hi Susan, Thank you for sharing this. I think it is very brave and shows that you are a very strong woman. I really want to commend you for taking a negative situation and turning it into something positive that may help other people. I really respect that. My father committed suicide when I was nine, so I know the kinds of feelings and unanswered questions that must be surrounding you and your family right now.

He is gone now. And who is she now that he’s gone? Susan is still a lawyer, a mother, a daughter, a friend and a neighbour. But after 28 years of being a wife, she has suddenly and unexpectedly become a widow. With him, she’d looked forward to visiting Ireland for the first time in September, and the next holiday that would take their troupe of Wilston walking friends to Iceland in mid 2018. The pair of them talked of retiring to Lake Cootharaba, north of Noosa, where he could sail his Heron boat to his heart’s content. They had so many plans together.

If her kids did not live here, she is not sure she would want to stay in this house. A lot of meaning has gone from the things she used to enjoy, especially with him, but their lives are not sitting still. The five of them usually sit down for a family meal each night. In November, two of her sons will compete in the Noosa Triathlon as part of the Beyond Blue team, and she is proud that they have raised more than $22,000 to help make depression, anxiety and suicide part of everyday conversations.

She did not cry much during the first few weeks after he died, not even at the funeral, but now she finds herself becoming tearful at the sight of small things around the house on the hill they shared for 25 years. She can’t bear to touch his toothbrush. Seeing his towel, or his clothes, sets her off. It’s in those everyday totems that Susan finds herself missing him the most.

I wish I wasn’t here giving this speech in these circumstances, Dad. I wanted to see you there at my graduation ceremony in two months. I wanted you to be there for my wedding. I wanted you to become the wonderful grandfather you would have been. I want you to be remembered for all the good things in your life and not for its tragic conclusion.

— John, eldest son

Rather than avert her eyes from this deadly, unknowable beast called suicide, she met its gaze and spoke its name. In Susan, the beast has found a formidable foe. It thrives in darkness and secrecy, and her flare lit up the night. In 2015, 3027 Australians died of suicide; three quarters of them were men. She thinks that number is way too high.

Her greatest frustration is that Andrew never said to her: Sue, I’m struggling. Sue, I’m not coping. Sue, I need some help. If he had said any of those things, she would have been onto it in an instant. She wants people reading this to look closely at the people who don’t whinge. Look at the people who don’t talk about their problems, because they might be suffering, and they can’t bring themselves to talk about it. Think: depression. Think: they need help. Think: I’m going to have to force the issue. Don’t think you are immune from experiencing mental illness. If it happened to him — someone who loved life so much — it can happen to anyone.

Andrew was proud of his wife and he loved her. His suicide changes neither of these facts, and it has not broken her. She has not crumbled. Somehow, she has strengthened, and when her words were read around the world, people ran toward her.

Susan does not think she is brave or courageous to have written that email, but she is wrong. In her honesty we saw her pain, and we wrote back to her with our deep, dark secrets and confessions, some of which we dared not speak aloud. Writing to her helped us. She did not know it when she wrote that email, but we needed Susan Bryant then, and we need her now.

Dear Susan, for five years, we have battled with my daughter’s depression, so we have drunk from the same cup. When I returned from active service in 2000, I came back with depression, for which I still take medication, but am well. Such a catastrophe as Andrew’s death has made me reassess values, attitudes and perspectives as well as ambitions. This has pressed my reset button, and sweetened life.

For help: Suicide Call Back Service 1300 659 467; Lifeline 13 11 14, Survivors of Suicide Bereavement Support 1300 767 022.